Stone

Otto Frödin’s excavations

Hans Browall has published the non-flint lithic assemblage from Otto Frödin’s excavation extensively (Browall 2011:203-254; tabell 49-101). Most of the stone artefacts from these excavations have been registered in the museum database.

Fig. 1. Non-flint lithic artefacts from Frödin’s excavations (file will be downloaded shortly).

Mats P. Malmer’s excavations

Recording of the stone artefacts

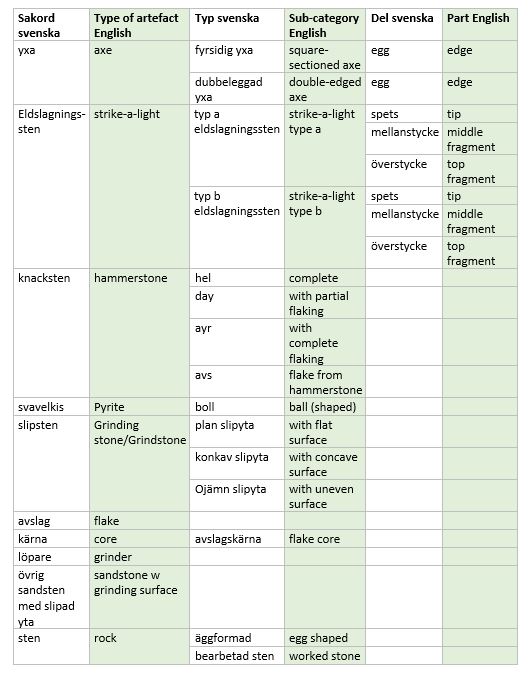

The stone artefacts from the Alvastra pile dwelling were recorded in accordance to the scheme used for Frödin’s excavations 1909-1930 (in Browall 2011). Definitions with slight adjustments can be found in the list of artefacts below. Registration had to be performed in Swedish, due to set parameters within the museum’s digital recording system, though all terms were subsequently translated to English (see fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Translations

Method

Information regarding find context is recorded for every find but varies depending on the available context information. The information includes some combination of x/y-coordinates, level (z), find no., feature number, type of feature, year of excavation, trench, layer and other relevant context information.

An analogue basic recording of the stone artefacts was done after each season of excavation 1976-1980. The find numbers generated during that recording are passed on to the digital recording as a find number (fyndnummer).

Each find is recorded based on the type of artefact (sakord), sub-type (typ), part (del), material (material), number of finds (antal ex) and number of fragments (antal fragment). Though kept to a minimum, finds are sometimes further described in the description (beskrivning). Any other comments relating to the find can be found as a note (anmärkning).

The raw materials used for the stone artefacts were geologically determined by Erik Åhman during or in connection to the excavation. The rock types present in the Western, Middle, Eastern, Trial trench and New trial trench can be found in fig. 3.

| Rock types in Swedish | Rock types in English |

| Amfibolit | Amphibolite |

| Aplit | Aplite |

| Arkos | Arkose |

| Bergart (samlingsbegrepp) | Undetermined rock |

| Biotit gnejs | Biotite-gneiss |

| Biotit leptit | Biotite-leptite |

| Dalaporfyr | Dala Porphyry |

| Diabas | Diabase |

| Diorit | Diorite |

| Dioritisk grönsten | Diorite-greenstone* |

| Glimmerskiffer | Schist |

| Gnejs | Gneiss |

| Gnejsgranit | Gneiss-granite |

| granit | Granite |

| Grönsten | Greenstone* |

| Hälleflinta | Halleflint |

| Jotnisk sandsten | Jotnian sandstone |

| Kalksten | Limestone |

| Kalktuff | Tufa |

| Kvarts | Quartz |

| Kvartsit | Quartzite |

| Kvartsitglimmerskiffer | Quartzitic schist |

| Kvartsitisk sandsten | Quartzitic sandstone |

| Leptit | Leptite |

| Leptitporfyr | Leptite-porphyry |

| Lerskiffer | Shale |

| Limonit | Limonite |

| Metavulkanit | Metavolcanic rock |

| Orsten | Anthraconite |

| Ortocerkalksten | Orthoceratite limestone |

| Porfyr | Porphyry |

| Porfyrisk metavulkanit | Porphyric metavolcanic rock |

| Porfyrit | Porphyrite |

| Sandsten | Sandstone |

| Skiffer | Slate |

| Skiffrig amfibolit | Slaty amphibolite |

| Skiffrig grönsten | Slaty greenstone |

| Smålandsgranit | Småland-granite |

| Visingösandsten | Visingö-sandstone |

| Växjögranit | Växjö-granite |

| *Greenstone is an archaeological collective term for several diabases and basalts that are dark/dark-green in colour. |

Fig. 3. Lithic materials used

Stone artefacts

Axe (yxa)

Axes were sub-categorised into two types; square-sectioned axe (fyrsidig yxa) or double-edged axe (dubbeleggad yxa). When the part (del) of the axe could be distinguished, this was also recorded as edge (egg) or butt fragment (nackfragment).

Fig. 4. Object number 1218499. Double-edged axe, preform, stone. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Complete axes and axe fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in the database. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete axes while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for axe fragments.

Strike-a-light (eldslagningssten)

Strike-a-lights were sub-categorised into two types; strike-a-light type a (typ a eldslagningssten) or strike-a-light type b (typ b eldslagningssten; Browall 2011:226ff.). When the part (del) of the strike-a-light could be distinguished, this was also recorded as tip (spets), middle fragment (mellanstycke) or top fragment (överstycke; Browall 2011:fig. 247).

Fig. 5. Object number 1281704. Strike-a-light, type A, leptite. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Complete strike-a-lights and strike-a-light fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in the database. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete strike-a-lights while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for strike-a-lights fragments.

Hammerstone (knacksten)

Hammerstones were sub-categorised into four types; complete (hel), with partial flaking (delvis med avslagsyta – day), with complete flaking (avslagsytor runt om – ayr) or flake from hammerstone (avslag – avs; Browall 2011:231ff).

Complete hammerstones and hammerstone fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in the database. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete hammerstones while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for hammerstone fragments.

Pyrite (svavelkis)

There was only one sub-type of pyrite ; ball-shaped (boll; cf, Browall 2011:235ff).

Fig. 6. Object number 1254747. Pyrite ball. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Complete pyrites and pyrite fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in the database. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete pyrites while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for pyrite fragments.

Grinding stone (slipsten)

Grinding stones were sub-categorised into three types (Browall 2011:238ff.); with flat surface (plan slipyta), with concave surface (konkav slipyta) or with uneven surface (ojämt slipyta).

Complete grinding stones and grinding stone fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in MIS. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete grinding stones while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for grinding stone fragments. Smaller fragments of possible grinding stones, but that were too small to be positively defined as such, are recorded as “Sandstone with ground surface” (listed below).

Flake (avslag)

Flakes are defined as a knapped fragment which contains a platform and a percussion bulb. It must be larger than 10 mm at its widest point.

Flakes were not sub-categorised. All flakes (fragments and complete flakes) were recorded in the field number of finds (antal ex). There is no separation between complete and fragmented flakes, in accordance with the applied recording scheme for flint (Andersson et al. 1978).

Core (kärna)

Cores were sub-categorised into one type; flake core (avslagskärna).

Complete cores and core fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in the database. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete cores while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for core fragments.

Grinder (löpare)

Is the rounded hand-held grinding stone commonly used in combination with a flat quern stone. The grinder can be distinguished through areas with clear signs of grinding.

Complete grinders and grinder fragments were distinguished from each other in the digital recording by using different fields in the database. The field number of finds (antal ex) was used for complete grinders while the field number of fragments (antal fragment) was used for grinder fragments

Sandstone with ground surface (övrig sandsten med slipad yta)

Sandstone with ground surface. These artefacts might be fragments of a grinding stone but are too small to be determined as such.

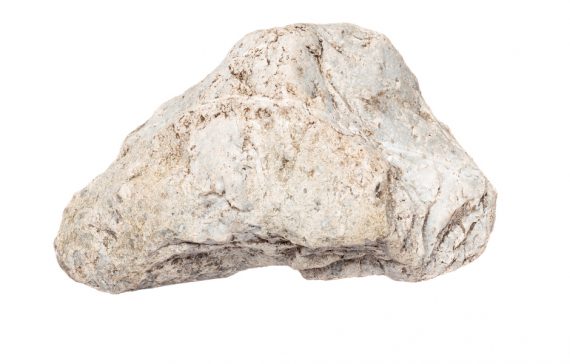

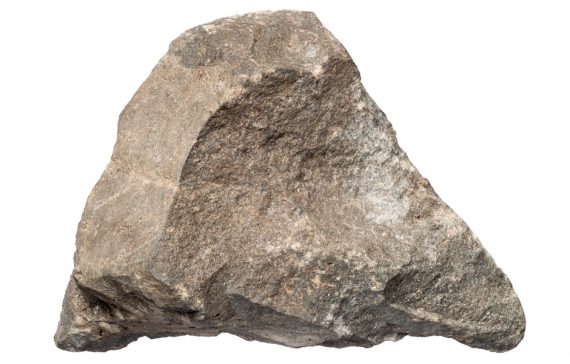

Debitage (debitage/bearbetad sten)

Worked pieces of stone that could not be determined as one of the other artefact types.

Text: Gregory Hayden Strand Tanner, Sandra Söderlind

Stone from the Eastern trench

The stone finds from the Eastern trench consisted of 367 objects. The artefact types and amounts can be found in fig. 7.

| Type of artefact | Number of finds | Percent |

| Axes | 9 | 2,4% |

| Strike-a-lights | 60 | 16,3% |

| Hammerstones | 38 | 10,3% |

| Pyrite balls | 19 | 5,1% |

| Grinding stones | 14 | 3,8% |

| Grinder | 1 | 0,2% |

| Flakes | 49 | 13,3% |

| Debitage | 55 | 15,0% |

| Microflakes | 5 | 1,3% |

| Sandstone w ground surface | 113 | 30,8% |

| Point | 1 | 0,2% |

| Cores | 3 | 0,8% |

| Total | 367 | 100,00% |

Fig 7. Stone finds from Eastern trench

The most common stone artefacts from the Eastern trench are sandstone with ground surfaces (30,8%) and strike-a-lights (16,3%).

A multitude of raw materials have been used for the different types of artefacts. The point is made of slate. The axe fragments are made from slatey amphibolite, which is a raw material commonly used for axes at Alvastra. The strike-a-lights are made from quartzite, leptite, halleflint and unclassified stone. Hammerstones are made from leptite, quartzite, granite, leptite-porphyry, amphibolite, halleflint, gneiss and unclassified stone. Grinding stones and sandstones with ground surfaces are both made from sandstone. Common remains from knapping or reworking of stone artefacts, such as flakes, debitage and microflakes, are made of quartzite, amphibolite, slatey amphibolite, leptite, sandstone, halleflint and unclassified stone.

Fig. 8. Object number 1218524. Double-edged axe, preform, stone. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Fig. 9. Object number 1211538, Tanged point, slate. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Discussion

The stone artefacts present in the Eastern trench provide indications of some activities that took place at the site. Pyrite has long been known to react with flint to create sparks used to start fires. It is less known that pyrite, to the same extent, can react with raw materials such as quartzite, quartz, basalt (Cave-Browne 1992). The pyrite along with flints and strike-a-lights made from other lithic raw materials could therefore all play a role in the creation of fire at the pile dwelling. The extensive use of fire at the pile dwelling has been previously discussed by Browall 2011 (p. 413) as a part in ritualistic activities such as food offerings and communal feasts.

Fig. 10. Object number 1220066. Strike-a-light, type A , leptite. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Fig. 11. Object number 1254750. Pyrite. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Fig. 12. Object number 1254776. Pyrite. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Fig. 13. Object number 1254892. Pyrite. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

The amounts of sandstone with ground surfaces, in their fragmented form or in the shape of grinding stones, indicate that the grinding of grains and seeds was an activity done on the pile dwelling. It is also possible that grinding stones were used to grind and form tools of flint or bone on site.

The presence of flakes, cores, debitage and microflakes indicate that knapping or reworking of stone artefacts was performed in this area of the pile dwelling, but most probably in moderation. It could also be the case that the preparation of these tools was done elsewhere, in another part of the pile dwelling or at another site. Hammerstones of different raw materials, and therefore different levels of hardness, were found at Alvastra which supports the notion that flint (and stone) were knapped at the pile dwelling.

A petrographic study showed that most of the lithic raw materials used at Alvastra are present in close vicinity to the pile dwelling (Browall 2011: 251-254). Flint is one exception to this. Petrographic studies of a larger geographical scale could further the understanding of raw material usage at Alvastra as well as contacts and mobility in the surrounding landscape.

Text: Gregory Hayden Strand Tanner

Stone from Western trench and Trial trench

Western trench

The stone finds from the Western trench consisted of 72 finds in 67 records. The artefact types and amounts can be found in fig. 14.

| Type of artefact | Without polished

surface |

With polished surface | Total | Percent |

| Axe fragment | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1,4% |

| Strike-a-light | 12 | 0 | 12 | 16,7% |

| Hammerstone | 9 | 0 | 9 | 12,5% |

| Pyrite | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1,4% |

| Grinding stone | 5 | 0 | 5 | 6,9% |

| Flake | 5 | 1 | 6 | 8,3% |

| Core | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1,4% |

| Debitage | 6 | 6 | 12 | 16,7% |

| Microflake | 7 | 0 | 7 | 9,7% |

| Sandstone w grinding surface | 18 | 0 | 18 | 25,0% |

| Total | 65 | 7 | 72 | 100,0% |

| Percent | 90,3% | 9,7% | 100,0% |

Fig 14. Stone artefacts from the Western trench.

The most common stone artefacts from the Western trench are sandstones with grinding surface (25%), strike-a-lights (16,7%) and debitage (16,7%). A few finds, 9,7%, have polished surfaces. These finds are concentrated to the categories debitage and flakes.

A multitude of raw materials have been used for the different types of artefacts. Many of the rock types can be found locally around Alvastra but some seem to be imported (Browall 2011: 251-254). The axe fragment is made from slatey amphibolite, which is a raw material commonly used for axes at Alvastra. However, it is not commonly found in the local landscape and is likely imported. The strike-a-lights on the other hand are made from leptite, leptite-porphyry, quartzite and Dala porphyry. Hammerstones are made from diorite, granite and leptite. Grinding stones and sandstone with ground surface are both made from sandstone. The flakes found in the trench are made from leptite, halleflint, aplite, sandstone, quartzite and undetermined rock. The one core found, a flake core, is made of leptite. The debitage consists of leptite and quartzite and the raw materials displayed in the micro flakes are leptite, halleflint, quartzite.

Trial trench

The stone finds from the Trial trench consisted of 5 finds in 5 records. The artefact types and amounts can be found in fig. 15.

| Type of artefact | Total | Percent |

| Hammerstone | 1 | 20,0% |

| Grinder | 1 | 20,0% |

| Debitage | 2 | 40,0% |

| Sandstone w grinding surface | 1 | 20,0% |

| Total | 5 | 100,0% |

Fig 15. Stone artefacts from the Trial trench.

The Trial trench contained very few stone finds, only 5 in total, and none of them have a polished surface. The hammerstone and grinder are made from leptite. The debitage is made from leptite and diorite and the sandstone with grinding surface is made of sandstone.

Discussion and observations

The materials from the Western trench and Trial trench will be discussed collectively. The stone artefacts found in these trenches provide a glimpse of the activities that took place at the site. Pyrite has long been known to react with flint to create sparks used to start fires. It is less known that pyrite, to the same extent, can react with raw materials such as quartzite, quartz and basalt (Cave-Browne 1992). The pyrite along with flints and strike-a-lights made from other lithic raw materials could therefore all play a role in the creation of fire at the pile dwelling. The extensive use of fire at the pile dwelling has been previously discussed by Browall (2011: 413) as a part in ritualistic activities such as food offerings and communal feasts.

The amounts of sandstone with ground surface, in their fragmented form or in the shape of grinding stones indicate that tools were ground on site. A hand-held grinder, commonly used with a quern stone, indicates that grinding of grains was another activity done at Alvastra.

The low numbers of flakes, cores, debitage and micro flakes still indicate that knapping or reworking of stone artefacts was performed in this area of the pile dwelling, but most probably in moderation. It could also be the case that the preparation of these tools was done elsewhere, in another part of the pile dwelling or at another site. Hammerstones of different raw materials, and therefore different levels of hardness, were found at Alvastra which supports the notion that flint (and stone) were knapped at the pile dwelling.

A petrographic study showed that many of the lithic raw materials used at Alvastra are present in close vicinity to the pile dwelling (Browall 2011: 251-254). Flint is one exception to this. Petrographic studies of a larger geographical scale could further the understanding of raw material usage at Alvastra as well as contacts and mobility in the surrounding landscape.

Text: Sandra Söderlind

Stone from the Middle trench

The stone finds from the Middle trench consisted of 118 finds in 112 records. The artefact types and amounts can be found in fig. 16.

| Type of artefact | Without polished surface | With polished surface | Total | Percent |

| Axe fragments | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1,7% |

| Strike-a-light | 25 | 0 | 25 | 21,2% |

| Hammerstone | 17 | 0 | 17 | 14,4% |

| Pyrite | 10 | 0 | 10 | 8,5% |

| Grinding stone | 7 | 0 | 7 | 5,9% |

| Flake | 15 | 6 | 21 | 17,8% |

| Debitage | 12 | 0 | 12 | 10,2% |

| Microflakes | 8 | 0 | 8 | 6,8% |

| Sandstone w ground surface | 16 | 0 | 16 | 13,6% |

| Total | 112 | 6 | 118 | 100,0% |

| Percent | 94,9% | 5,1% | 100,0% |

Fig 16. Stone artefacts from the Middle trench.

The most common stone artefacts from the Middle trench are strike-a-lights (21,2%), flakes (17,8%) and hammerstones (14,4%). A few finds, 5,1%, have polished surfaces. The only type of find with polished surface is flakes.

A multitude of raw materials have been used for the different types of artefacts. The axe fragments are made from slatey amphibolite, which is a raw material commonly used for axes at Alvastra.

The strike-a-lights are made from quartzite, leptite, halleflint and undetermined rock. Hammerstones are made from leptite, quartzite, granite, leptite-porphyry, amphibolite, halleflint, gneiss and undetermined rock.

Fig. 17. Object number 1281693. Strike-a-light, type A, quartzite. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

Grinding stones and sandstone with ground surface are both made from sandstone. Common remains from knapping or reworking of stone artefacts, such as flakes, debitage and microflakes, are made of quartzite, amphibolite, slatey amphibolite, leptite, sandstone, halleflint and unknown stone.

Discussion:

The stone artefacts present in the Middle trench provide indications of some activities that took place at the site. Pyrite has long been known to react with flint to create sparks used to start fires. It is less known that pyrite, to the same extent, can react with raw materials such as quartzite, quartz, basalt (Cave-Browne 1992). The pyrite along with flints and strike-a-lights made from other lithic raw materials could therefore all play a role in the creation of fire at the pile dwelling. The extensive use of fire at the pile dwelling has been previously discussed by Browall 2011 (p. 413) as a part in ritualistic activities such as food offerings and communal feasts.

Fig. 18. Object number 1281761. Pyrite ball. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish History Museum.

The amounts of sandstone with ground surface, in their fragmented form or in the shape of grinding stones, indicate that the grinding of tools was an activity done at the pile dwelling.

The presence of flakes, cores, debitage and micro flakes indicate that knapping or reworking of stone artefacts was performed in this area of the pile dwelling, but most probably in moderation. It could also be the case that the preparation of these tools was done elsewhere, in another part of the pile dwelling or at another site. Hammerstones of different raw materials, and therefore different levels of hardness, were found at Alvastra which supports the notion that flint (and stone) were knapped at the pile dwelling.

A petrographic study showed that most of the lithic raw materials used at Alvastra are present in close vicinity to the pile dwelling (Browall 2011: 251-254). Flint is one exception to this. Petrographic studies of a larger geographical scale could further the understanding of raw material usage at Alvastra as well as contacts and mobility in the surrounding landscape.

It is important to keep in mind that the trench discussed in this text only amount to a small part of the entire Alvastra pile dwelling site. These findings will need to be understood in relation to finds from other trenches.

Text: Sandra Söderlind

Stone artefacts from all trenches

| Type of artefact | Number of finds | Percent |

| Axes | 12 | 2,1% |

| Strike-a-lights | 97 | 17,4% |

| Hammerstones | 64 | 11,4% |

| Pyrite balls | 30 | 5,3% |

| Grinding stones | 26 | 4,6% |

| Grinder | 1 | 0,1% |

| Flakes | 76 | 13,6% |

| Debitage | 79 | 14,1% |

| Microflakes | 20 | 3,5% |

| Sandstone w ground surface | 147 | 26,3% |

| Point | 1 | 0,1% |

| Cores | 4 | 0,7% |

| Total | 558 | 100,0% |

Fig 19. Stone artefacts from all trenches.

Four of the axes are double-edged axes of slatey amphibolite.

Seven are square-sectioned axes and one is so eroded that the type cannot be determined. An interesting find is a large piece of amphibolite, not slatey, presumably intended for the production of an axe of some kind.

Otto Frödin’s and Mats P. Malmer’s excavations – non-flint stone

This assemblage contains several types that are unusual at other Stone Age sites. The double-edged shafthole axes are not unusual as such but at Alvastra they were found in unusually large numbers. Around 350 axes are known from Sweden and around 58 come from the pile dwelling (53 from Frödin’s excavations and five from Malmer’s; Browall 2003:55). What is more, they are of a characteristic stone, slatey amphibolite, that is unusual or non-existent at other sites.

Fig. 20. Artefacts of slatey amphibolite from Otto Frödin’s excavations (file will be downloaded shortly).

Fig. 21. Artefacts of slatey amphibolite from Mats P. Malmer’s excavations (file will be downloaded shortly).

Pyrite balls have been only found at three other Stone Age sites on Gotland and in Halland (Browall 2011:236). They are available in large numbers at Alvastra.

Strike-a-lights in non-flint stone are of a very characteristic type at the pile dwelling and they are unusual at other Stone Age sites, being know from two other sites in Alvastra (Broby and the Alvastra dolmen) and from one of the Siretorp sites in Blekinge (Browall 2011:227).

Unworked stone

Otto Frödin’s excavations

Unworked stone was collected during Frödin’s excavations. Unworked stone is one of the categories that is not fully registered in the museum database. Around 10% of the whole assemblage consists of unregistered unworked stone. Fig. 22 shows the unworked stone that is registered in the database.

Fig 22. Unworked stone from Frödin’s excavations registered in SHM: s database (file will be downloaded shortly).

Hans Browall has registered 1024 records of unworked stone weighing 34,5 kg (Browall 2011:250). The stone is listed in table 100 and the kinds of stone in the assemblage are compared with those that occur naturally in 10 sampling points in the surrounding area (Browall 2011:251 ff, tabell 101). This shows that the most common stone in the sampling points is also the most common stone in the excavated trenches (gnejs, granite, quartzite, leptite, sandstone). However, two types of stone show interesting differences.

Firstly, quartz is very uncommon in the sampling points and it is not prominent in the excavated trench, but it does exist. According to Browall the assemblage consists of 211 quartz objects which is 1.7% of the lithic material found during Frödin’s excavation. The quartz objects consist of unworked quartz (43) but also of 83 flakes, 3 cores, 62 pieces of debitage, 17 hammerstones and 3 strike-a-lights (Browall 2011:254). This is a great difference from the quartz assemblage found during Mats Malmer’s excavations (virtually non-existent, see below) and also in great contrast to other Neolithic sites in Östergötland (worked quartz dominant, Carlsson 2014:135). This, admittedly small, quartz assemblage needs to be studied in more detail and compared to assemblages in the surrounding area, not least to the quartz found under the Alvastra dolmen (Ahlbeck 2009:127 ff). These quartz flakes and debitage are not unworked but they are discussed in Browall’s publication under this heading.

Fig 23. Quartz registered in SHM:s database (file will be downloaded shortly).

The second difference is the complete absence of slatey amphibolite at the sampling points. This characteristic stone was primarily used to make the axes found at the pile dwelling (Browall 2011:254; fig. 5.12:8, 5.12:9). It is not found locally and no research into the provenance of this stone seems to have been conducted. Browall maintains that flakes and pieces of debitage “are well represented in the lithic assemblage” (Browall 2011:254, translation Jackie Taffinder). Fig. 21 (file will be downloaded shortly) shows these artefact categories are restricted to a flake, a platform core (designated in Browall’s tabell 98 as a possible axe preform) and four pieces of debitage. More may be found in the material not registered in the database as is suggested by Browall’s tables (2011: tabell 95, tabell 101). It is quite clear that more research into this matter should be undertaken.

Mats P. Malmer’s excavations

Registration

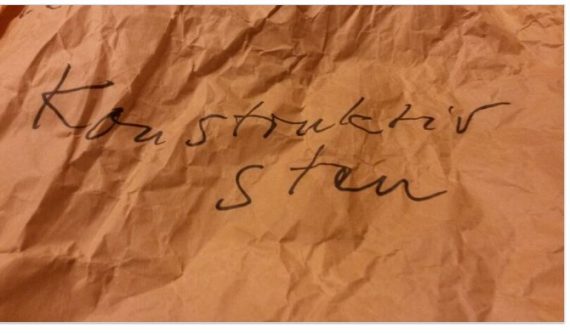

Non-constructive stone is a term used by Mats P. Malmer to describe the stone recovered in the pile dwelling not used in the construction of features such as fireplaces or cairns or in the manufacture of stone tools. We have not found any reference to this term in the available excavation documentation, but it is used in the labels of the lithic material itself. This term is used primarily in the labels of the lithic assemblage from the Eastern trench, but we have used it for such material deriving from all trenches.

Fig. 24. A label from original packaging of constructive stone. Photo:Jackie Taffinder, SHM

Constructive stone is the term used to describe the lithic material used to build features such as fireplaces. Again, this term is used primarily in finds labels of material from the Eastern trench, but we have used it to describe material from all trenches.

A note from Gunborg O. Janzon’s field diary of 16 June 1978 reports that Mats P. Malmer had introduced the term constructive stone also for stone which can hypothetically have been placed deliberately on top of a hearth.

In Mats P. Malmer’s excavation all lithic material, both constructive and non-constructive stone, was collected. We have registered all this collected stone. It is stored in plastic bags and osteology boxes on pallets in the external storerooms of the Swedish History Museum. Stone is not a natural feature of the fen, so all stone was transported to the site by people (Malmer 2016:374 to be downloaded shortly) and the use of stone is hence a potential research topic (Browall 2016:101 ff).

Rock type is registered under material. If the rock has not been identified the term stone is used (Swedish – bergart) in the database. Sometimes the material is described as K or Ka (limestone) on the find bags. On other bags S (sandstone) or G (granite) is used. According to Hans Browall (2016, appendix 1, p. 3) G can mean granite or other stone. The rock types registered on the find bags seem to consist of determinations made by individual archaeologists in the field. It is possible to see that some archaeologists have registered rock type more often than others. It is not certain that these determinations are correct. In spite of this, they have been registered in the database as it has not been possible, within the framework of the present project, to have the rock determined by a geologist. Indeed, in one case (Object number 1223164) G was the rock specified on the bag in the field and leptite is the determination noted sometime afterwards. In another case (Object number 1223169) G was the determination in the field but it was altered to gneiss sometime afterwards.

In some cases, the rock seems to have been identified by Erik Åhman, the geologist involved in Mats P. Malmer’s Alvastra excavations. These identifications seem to have been noted post-excavation on the bags. The bags are newer (not from the field) and the different rock types are stored in different bags. The determinations also cover a wider range of rock types than just granite, sandstone and limestone.

Thus, there are many problems for scholars wanting to conduct research into the use of different rocks in the pile dwelling. Erik Åhman seems to have petrographically classified most of the material in the Western Trench (Browall 2016:86) but this does not seem to have been the case for the other trenches. From the Western Trench some of the lithic material, i.e. that recovered from water-sieved soil, has not been subjected to petrographic classification (Browall 2016, p. 87). However, Browall’s table 61 in his publication of 2016 shows that none of the unworked blocks and stones are petrographically unidentified (Browall 2016: tabell 61). In the database many records in the Western Trench are unidentified (see fig. 25). All the available petrographic identifications have not been included in the database.

Some of the rock had disintegrated into soil, probably already at the point of excavation. Sometimes the find bags exhibit comments showing that the rock was already eroded when it was recovered from the excavation. In these cases, this is registered together with the petrographic classification, e.g. sandstone, eroded.

The non-constructive stone has been quantified according to weight. This is also the case for most of the constructive stone but if the constructive stones are very large, they have been quantified by number. Weights under 0,1 g have been registered as 0 g.

Two different kinds of scales have been used, one kind with weight to the nearest gram and one kind registering parts of a gram to one decimal. The former has primarily (but not only) been used for the lithic material stored on pallets.

Fig. 25. Non-constructive stone from Malmer’s excavations (file will be downloaded shortly).

Constructive stone

Fig. 26. Constructive stone from Malmer’s excavations (file will be downloaded shortly).

The following references cited on this page do not have a web link:

Ahlbeck, M., 2009. Vain quartz? In Janzon, G.O., 2009, The dolmen in Alvastra. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och antikvitets akademien, Handlingar. Antikvariska serien 47. Stockholm:127-134.

Browall, H., 2011. Alvastra pålbyggnad, 1909-1930 års utgrävningar. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. Handlingar. Antikvariska serien 48. Stockholm.

Browall, H., 2016. Alvastra pålbyggnad. 1976–1980 års utgrävningar. Västra schaktet. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och antikvitets akademien, Handlingar, antikvariska serien 52. Stockholm.