The History of Easter

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Easter is the most important festival in the Church year. Easter reminds us of the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus. The word “Easter” comes originally from the Jewish tradition and the Hebrew word pesach. Easter has been celebrated in Sweden for several hundred years, but certain traditions go back even further.

Easter traditions in Sweden

- The Easter cockerel: a biblical symbol that became widespread in Sweden. Jesus foretells that Peter will deny him “before the cock crows.”

- Easter witches: The tradition of children dressing up and going from house to house as påskkärringar has its roots in medieval folklore, which held that witches flew to Blåkulla to meet the Devil. This idea reflects old beliefs about the Devil from the time when Scandinavia was still Catholic.

- Easter twigs (påskris): introduced in the 19th century. The twigs recall how Jesus was scourged before the crucifixion.

- The Easter bunny has no connection to Christianity. Introduced from Germany in the 19th century.

A Viking-Age “easter egg”

There is a so-called resurrection egg in the collections of the Swedish History Museum dating from the late Viking Age and the early Middle Ages. Such finds are fairly rare in Sweden, but examples have been discovered in Sigtuna, Lund and on Gotland. Resurrection eggs originally came from the east, and archaeologists believe they were made in the Kiev region. The fact that similar eggs have been found on Gotland demonstrates the Vikings' contacts with the east as well as the exchange of goods and ideas.

The eggs are made of ceramic, covered with a thin layer of glaze. They are the same size as a normal hen’s egg and are thought to symbolise the Christian resurrection. Ordinary hen’s eggs have also been found in Viking-Age graves, and it is quite possible they carried a similar symbolism.

This particular egg was found on a settlement site in Sigtuna. Inside it there is a hollow space containing a small object, which means the egg could be used as a rattle.

Resurrection egg

A painted ceramic egg. Found in Sigtuna, Uppland.

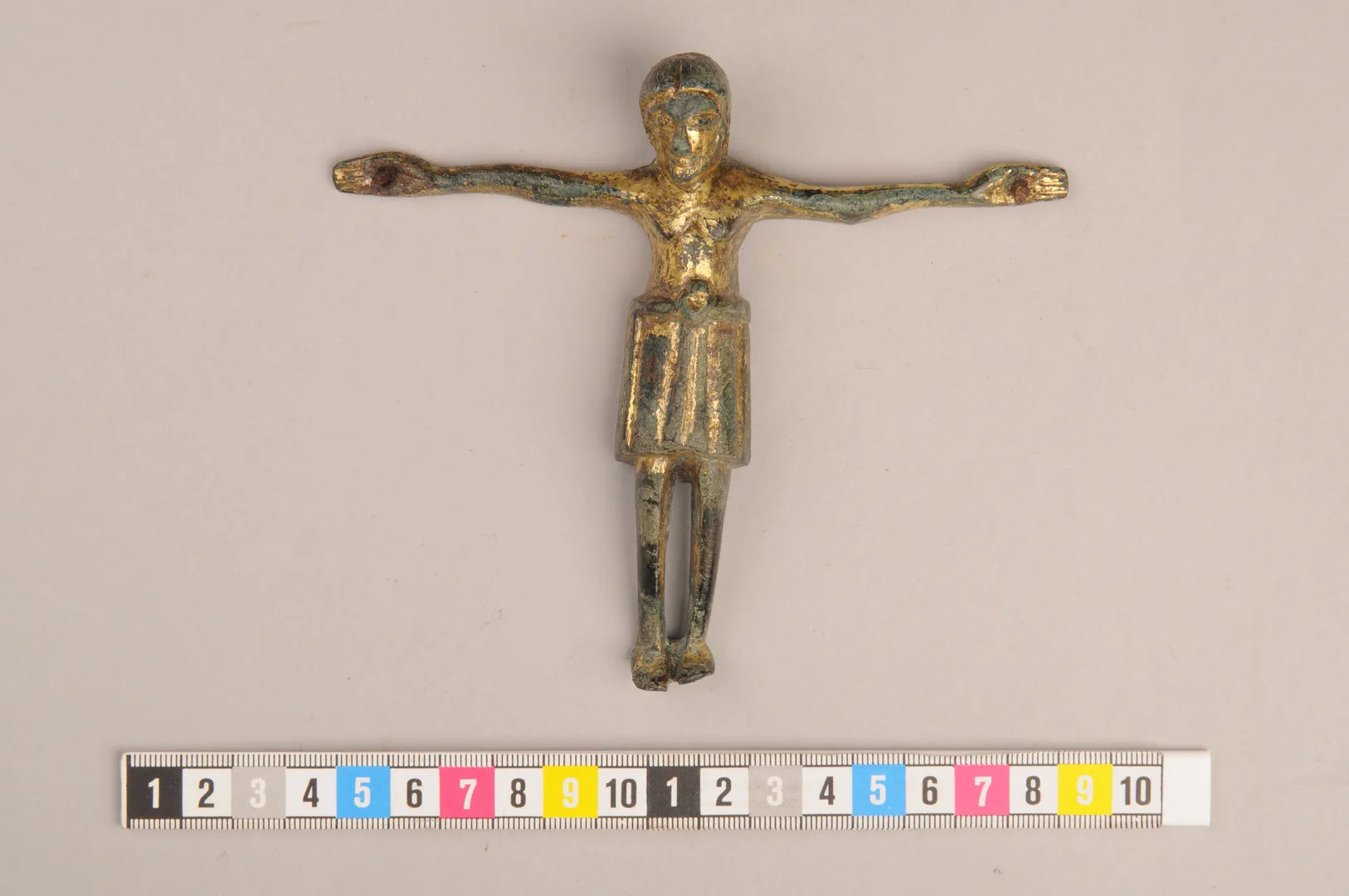

The crucified Christ

The Easter story tells of how Jesus was crucified, died, and rose again. This small bronze image of Christ, in the collections of the Swedish History Museum, probably once formed part of a cross that has long since disappeared. The nails fastening the hands to the cross are still there. The legs are parallel, and the feet stood on a small footrest, suppedaneum in Latin. This is how Christ is often depicted on crucifixes from the early Middle Ages. The word crucifix in its strict sense comes from Latin crucifixus, meaning the crucified one.

Crucifix

Found at an abbey in Södermanland.

The figure is not large, just over 12 centimetres high, yet oddly monumental in its smallness. The hair is long and parted in the middle, the eyes large and protruding. The head has not fallen to the side, and one may interpret the figure as standing with eyes open, triumphant over death. The image would have been fixed to a cross, which could be placed on an altar, or mounted on a staff and carried in processions.

The Christ figure comes from a church that no longer exists, but once stood in Eskilstuna. At the end of the 12th century, before 1185, the Hospitallers founded a monastery in Tuna, as the town was then called. The Hospitallers were an order that grew out of the work of running pilgrim hostels in the Holy Land. In time, it became a knightly order with monasteries across Europe. In Eskilstuna, the monastery survived until the 16th century; after the Reformation, the site became a royal manor, later a castle.

The Hospitallers took over the church already standing there, the Church of Saint Eskil. That church may have been built after the missionary Eskil’s martyrdom in the 11th century, and he is said to have been buried there. In 1231, Pope Gregory IX confirmed the Hospitallers’ possession of the church. It was probably in that church that the little crucifix was used.

Historians have suggested that the cross figure could have been made as early as the time of Saint Eskil, in the 11th century. However, a major scholarly work that catalogues virtually all surviving Christ figures of this type concludes that it is more likely from the mid-12th century. But where exactly did the object come from?

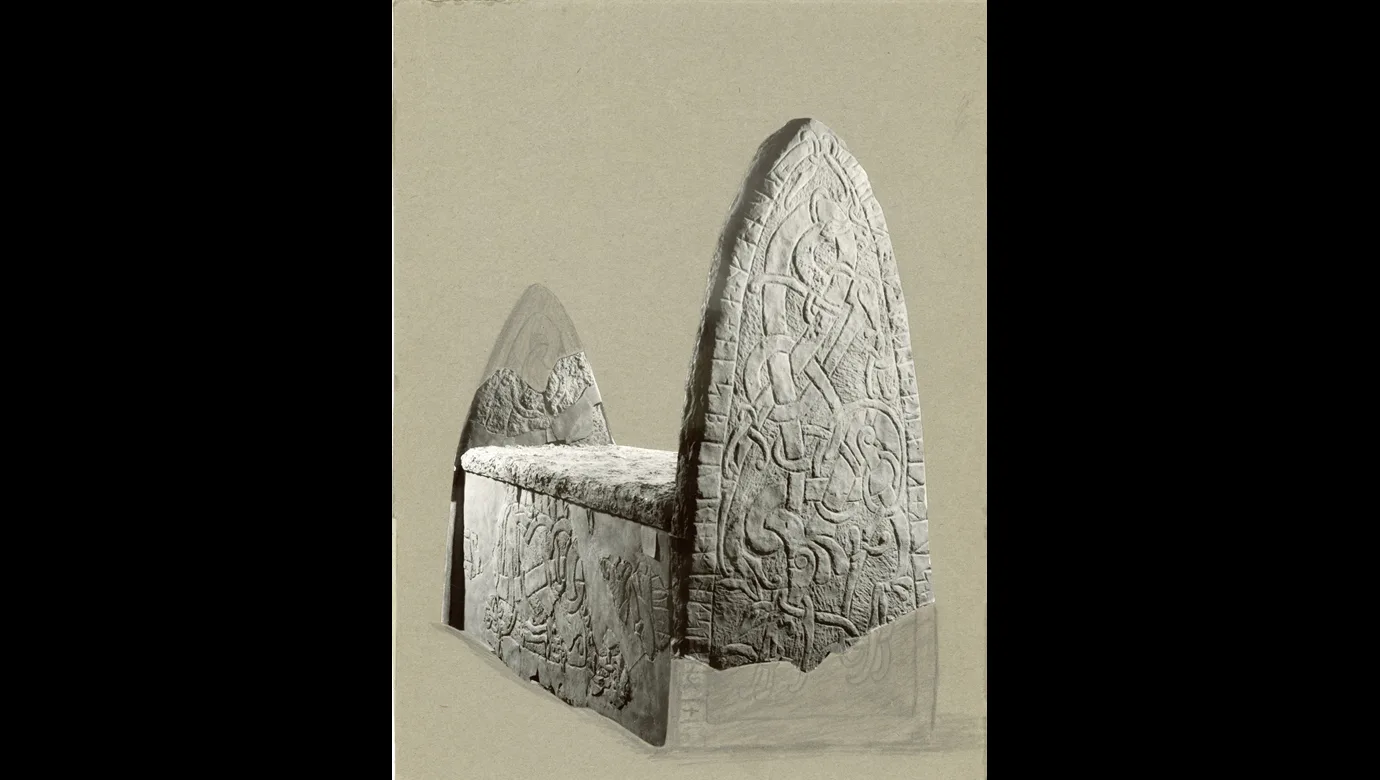

The Eskilstuna coffin – an early Christian monument

In 1912, while laying out a new street, Klostergatan, over the site of the former monastery and castle in Eskilstuna, workers uncovered four large slabs from a stone coffin, decorated with Viking-style ornaments.

The coffin had two pointed gable slabs, side slabs, and a lid. It resembled a runestone. Archaeologists at the time thought this design was unique to the area, and so it was called the “Eskilstuna coffin” (Eskilstunakista). Ever since, all such coffins of the same type have been given the same name, after this find. During the excavation, a private individual also “found” the small crucifix, which eventually came to the Swedish History Museum.

Today, you can see a replica of the Eskilstuna coffin in Klosters Church, Eskilstuna.