Sweden’s oldest book

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Marinus de Fregeno served as papal envoy in Sweden from 1457 until the early 1470s. His task was to raise funds for crusades, chiefly by selling . In the Middle Ages, people believed the soul was tormented after death in purgatory for sins committed during life. An indulgence could shorten this time. One way to atone for sins was to give money to the Church.

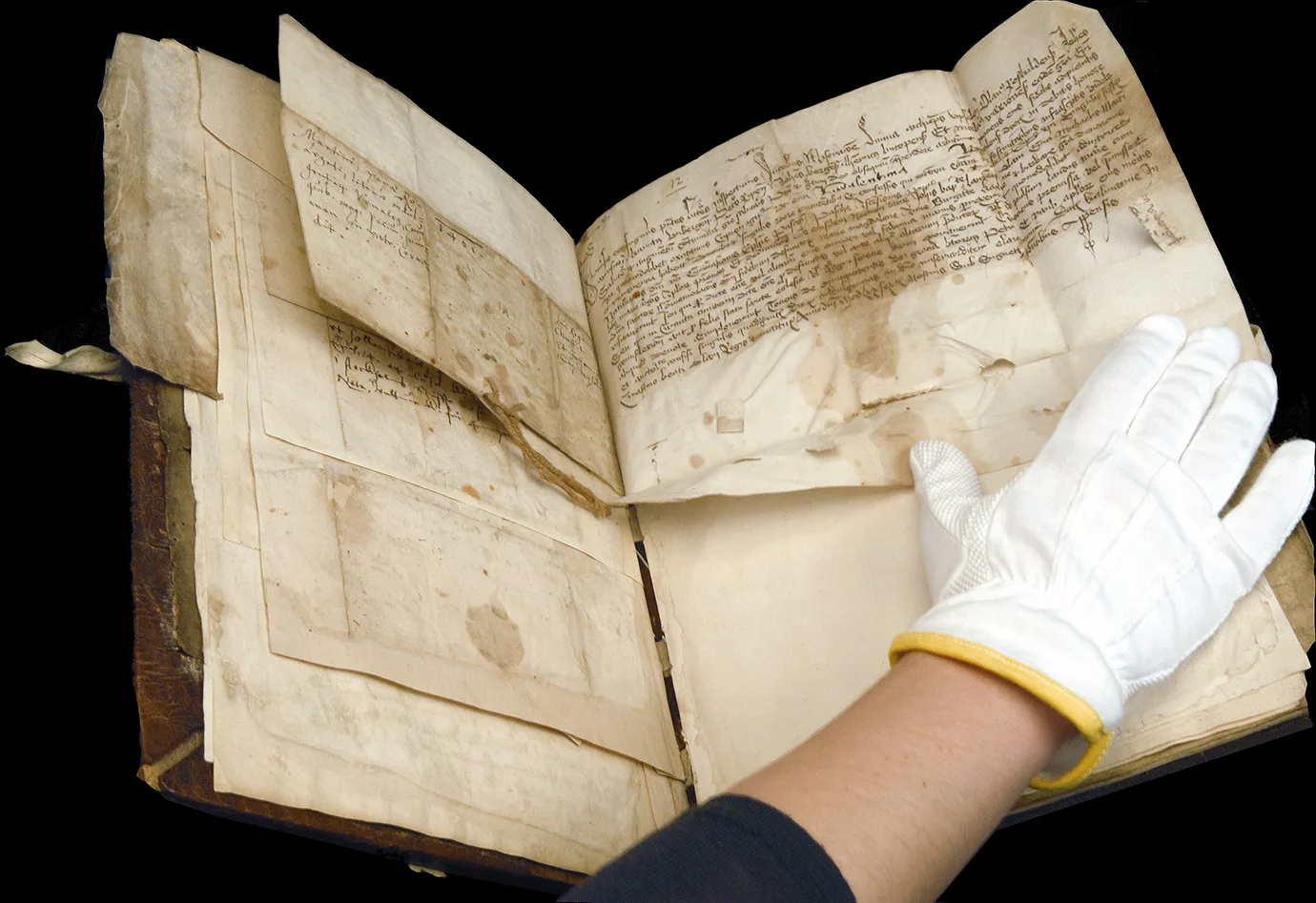

Marinus carried papal authority to issue such letters of indulgence. In the collections of the Swedish History Museum are both his seal matrix and an indulgence from 1461, granted to Lars Nilsson, Birgitta Olavsdotter and their five children. This document is bound together with other ecclesiastical papers in what is known as the Vallentuna calendar. But who exactly was Marinus de Fregeno? How did he come to Sweden, and how did he carry out his mission?

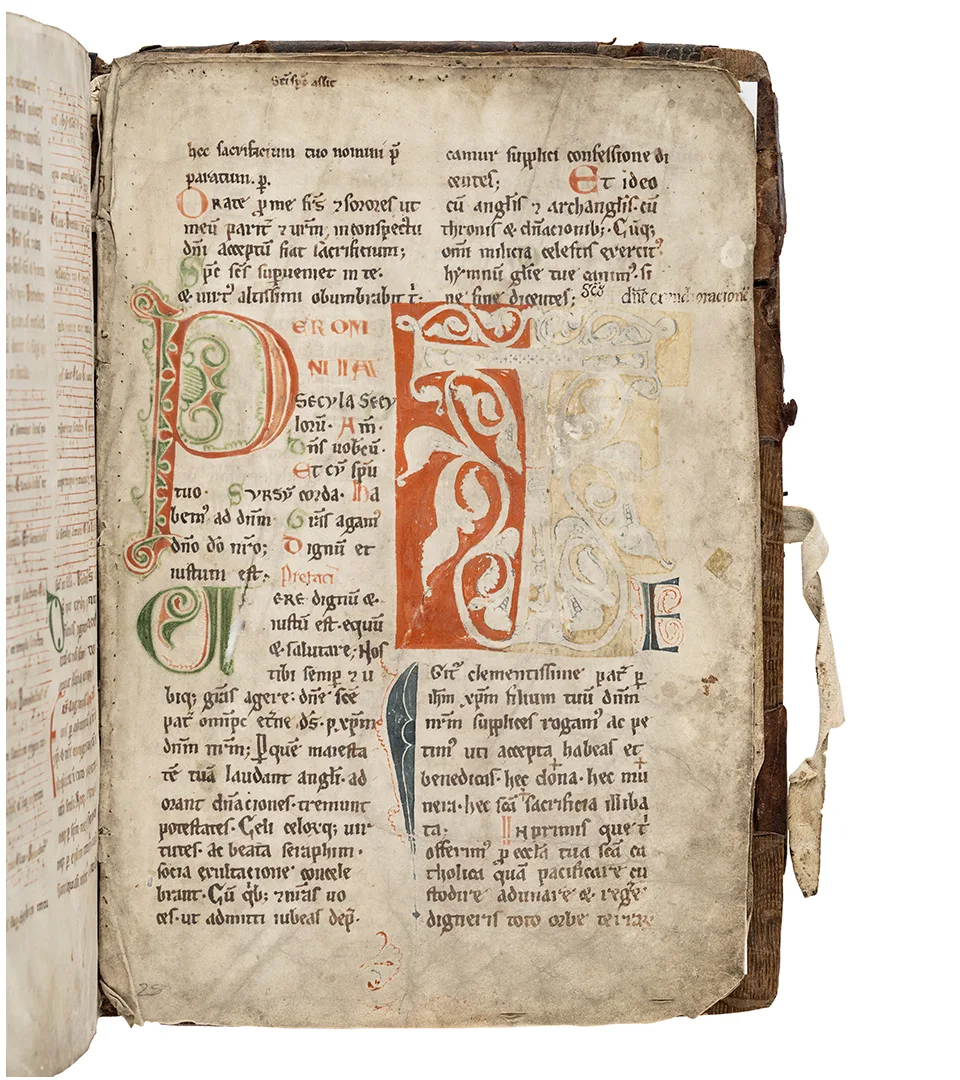

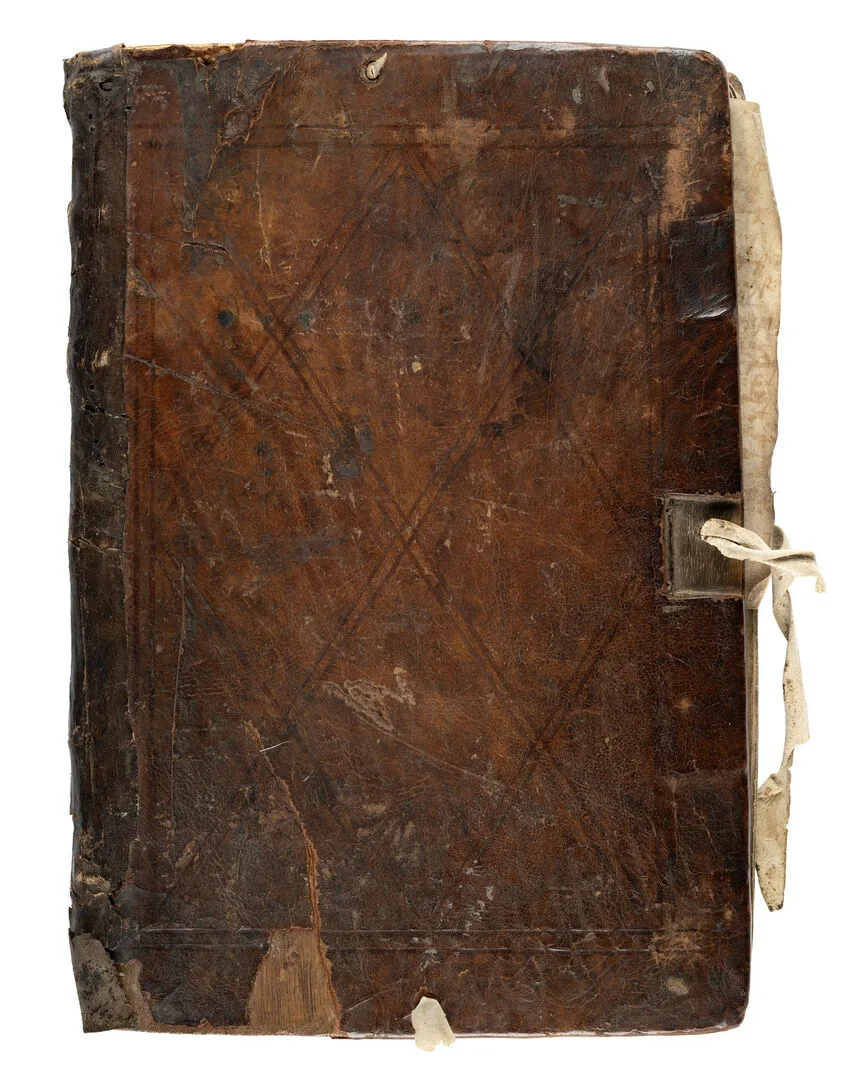

The Vallentuna calendar

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Medeltida liv

Travelling with a strong retinue

When appointed papal envoy in 1457, Marinus was in Parma, Italy. He may have travelled at once to one of the regions where he would be active. By 1459, he was working for the cathedral in Spoleto, and received papal permission to travel across Europe to distribute funds to kings and princes.

He may already have been in Sweden by 1459, but we know for certain that he was there in 1460. That year and the next, he issued numerous letters from towns in Uppland, Södermanland and Västmanland, suggesting that he spent these years moving between Uppsala and Strängnäs.

A medieval identity document

Today we prove our identity with signatures, ID cards or digital identification. In the Middle Ages, seals served that purpose. A seal was an impression in wax made with a seal matrix, showing both presence and authenticity.

Seal matrices were unique, marked with images, letters or symbols of their owner. Clerical seals often bore religious motifs such as chalices or the initials of the Virgin Mary. As they were personal, the seal was destroyed upon its owner’s death – and one certainly did not want to lose it.

The museum preserves a seal matrix bearing two crossed keys bound by a band beneath a papal tiara with three crowns. Its inscription shows that it belonged to Marinus de Fregeno and was used in connection with raising funds for a crusade against the Turks.

Marinus de Fregeno's seal

Losing the seal stamp

In 1462 Marinus travelled south to Östergötland and parts of Småland near Linköping. He visited the monasteries of Vadstena and Askeby, and issued indulgences for Vreta Abbey. He also reached Kalmar.

The seal stamp in the museum collections was found in the parish of Roma Abbey on Gotland. As the island lay within the diocese of Linköping, it may have been during this journey that Marinus visited Gotland and lost his seal.

In 1463 Marinus also became a priest at Strängnäs Cathedral, receiving as salary a prebend, a farm with arable land, the common form of clerical income in the Middle Ages. The following year he left Sweden, taking to Poland the funds he had raised for the crusades. He remained in contact with Sweden, acting for instance as envoy of the Swedish king in Rome in 1479.

Marinus ended his career as bishop of Kammin in Poland, dying sometime before 1486. He had once lost his seal matrix - but he was also, without doubt, a widely travelled man.