Staffan the stable boy

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

In the Acts of the Apostles, Stephen appears shortly after the death of Jesus, at a time when the number of disciples was rapidly increasing. The original twelve apostles needed help with the practical work of a growing congregation and appointed seven men as assistants. One of them was Stephen.

He did not limit himself to serving food but also preached and performed miracles. Eventually, he was dragged outside the walls of Jerusalem and stoned to death by an enraged mob. He thus became the first Christian martyr. Stephen was quickly venerated as a saint, and the church’s deacons made him their patron. His popularity gave rise to many legends about his life.

Stephen is depicted in one of the marvellous 13th-century paintings still visible on the wooden ceiling of Dädesjö Church in Småland. Just as in the ballads, he is shown “watering his horses.” The Star of Bethlehem is also present.

Detail from Dädesjö church, Småland. ID 9118012. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC BY 4.0)

The miracle of the cock and the massacre of the innocents

One of the legends tells how, on Christmas night, Stephen saw the Star of Bethlehem. He understood it as a sign that the King of Judah, who according to the prophecies would save the world, had been born. He reported his discovery to Herod. The king refused to believe him unless the roasted cock lying on his breakfast table were to rise up, flap its wings, and crow.

That is, of course, exactly what happened. Herod, terrified by the power of the newborn king, resolved to kill the child who threatened his rule. Stephen himself was seized and stoned to death outside the city walls.

The miracle of the cock, as the event came to be known, became the prelude to the massacre of the innocents. In the Middle Ages, it was widely believed that the massacre in Bethlehem was the first and perhaps the cruellest of all martyrdoms.

The miracle of the cock

Stephen is shown kneeling before King Herod at his table as the cock takes flight. Depiction on an altar frontal from Broddetorp Church in Västergötland, late 12th century.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Medeltida konst

The stable boy and the Star of Bethlehem

In medieval Scandinavia, the legend of Stephen took on its own form, in which horses played an important role. On Christmas night, Stephen rode to a spring to water Herod’s horses. One horse, however, refused to drink, having seen the reflection of the star in the water. It reared up in fear towards the night sky.

Images of Stephen with his horses, or in connection with the Cock Miracle, became popular in early medieval Scandinavian art. The motif often appeared on baptismal fonts as part of the story of Christ’s birth. In depictions of Stephen, he frequently holds stones, a reference to his martyrdom.

Stephen with stones

Sculpture from Läby church, Uppland.

The legend develops

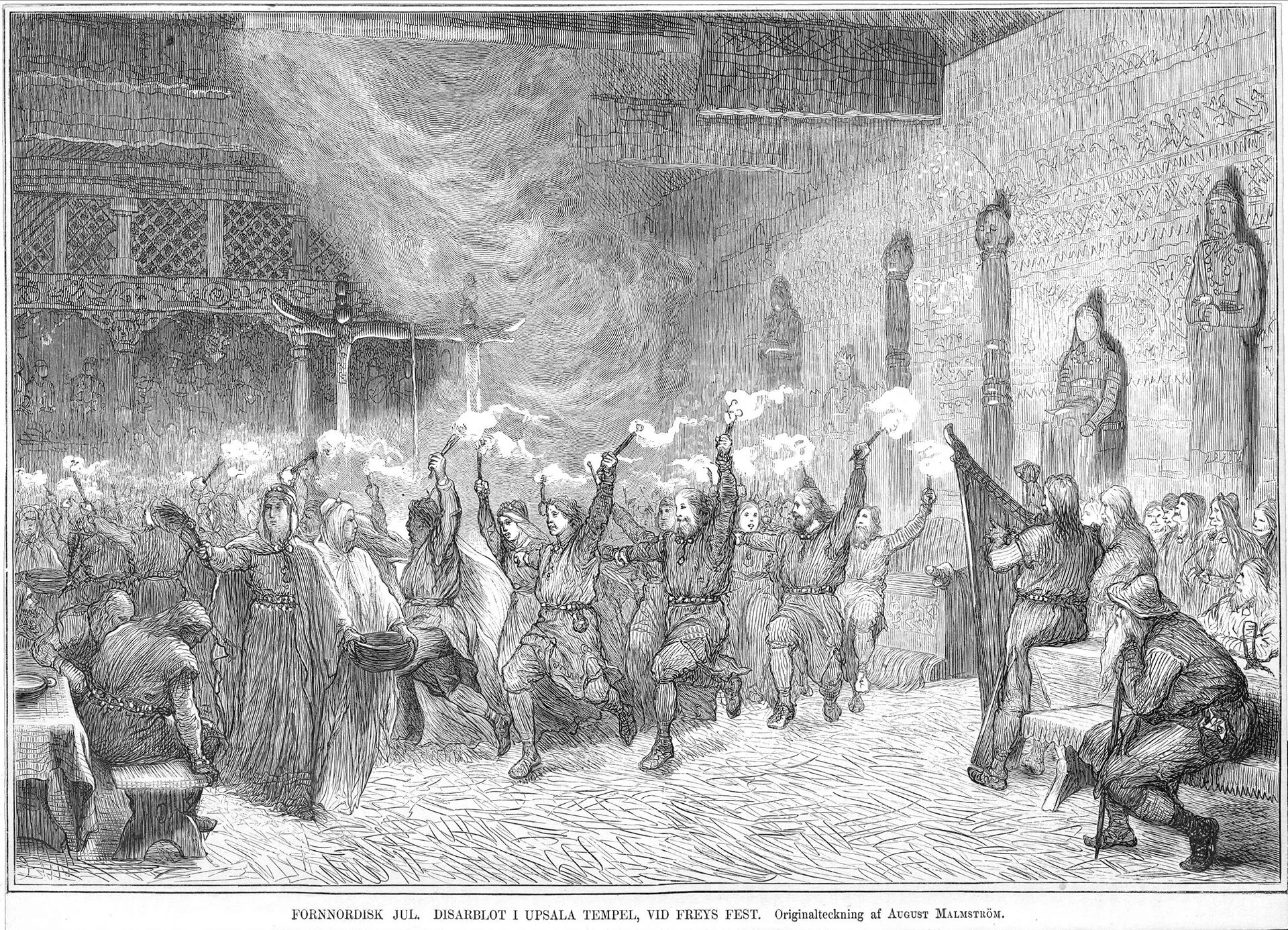

The popularity of the legend may be linked to the long and drawn-out process of Christianisation in what is now Sweden. Around the year 1100, much of the population was still pagan. It took nearly 300 years for Christianity to take firm root. During this extended missionary period, biblical stories were introduced alongside a growing cult of the saints.

The legend of Stephen and Herod was probably newly formed when it reached the North and was reshaped according to local traditions. In pre-Christian Nordic culture, the horse was central, and Yuletide was a time when special care was taken of one’s animals. Transforming pagan customs into Christian practice was one way for the new faith to establish itself. The legend of Stephen and Herod is a clear example of this.

With Gustav Vasa and the Reformation, the Catholic cult of saints, including that of Stephen, was abolished. Yet Staffan the stable boy never lost his popularity. Well into the 20th century he remained part of Christmas plays and the tradition of Staffanssång (to sing Staffan) on 26 December, Saint Stephen’s Day.

Sometime in the 19th century, Staffan was merged into the Epiphany singers and relegated to the feast of Saint Lucy (13 December) as part of her retinue. The connection to horses survives only in the songs, but the Star of Bethlehem remains, and the stable boy has become one of the star boys (stjärngossar).