Reading and writing in the Middle Ages

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Literacy was limited to a small segment of society. Wealthier families could afford to send their children to monastic schools, where instruction included reading, writing, arithmetic, and Latin – the principal language of learned and religious texts. An example of such manuscript culture is an from Gotland, preserved in the collections of the Swedish History Museum. Indulgence letters functioned as written confirmation of the remission of sins, obtainable through monetary payment. As a result, access to forgiveness and the promise of salvation was more readily available to the wealthy. The letter in question was bound into the Vallentuna Calendar, a manuscript compiled in 1198 containing a list of saints’ feast days and notes on the liturgical year.

Writing implements typically included quills fashioned from the wing feathers of birds, most commonly geese. Ink could be prepared from various substances, including carbon. Texts were written on parchment or wax tablets; from the late Middle Ages onwards, paper increasingly supplanted these earlier materials.

A medieval pen

This stylus (pen) is made of ivory from around 1100–1500. Found in Alvastra Abbey, Östergötland.

Medieval spectacles

The development of spectacles represents a significant technological innovation of the later Middle Ages. Although their inventor remains unknown, documentary evidence confirms their existence by the late 13th century. Their adoption was particularly marked among literate groups such as clergy, members of monastic communities, and the nobility.

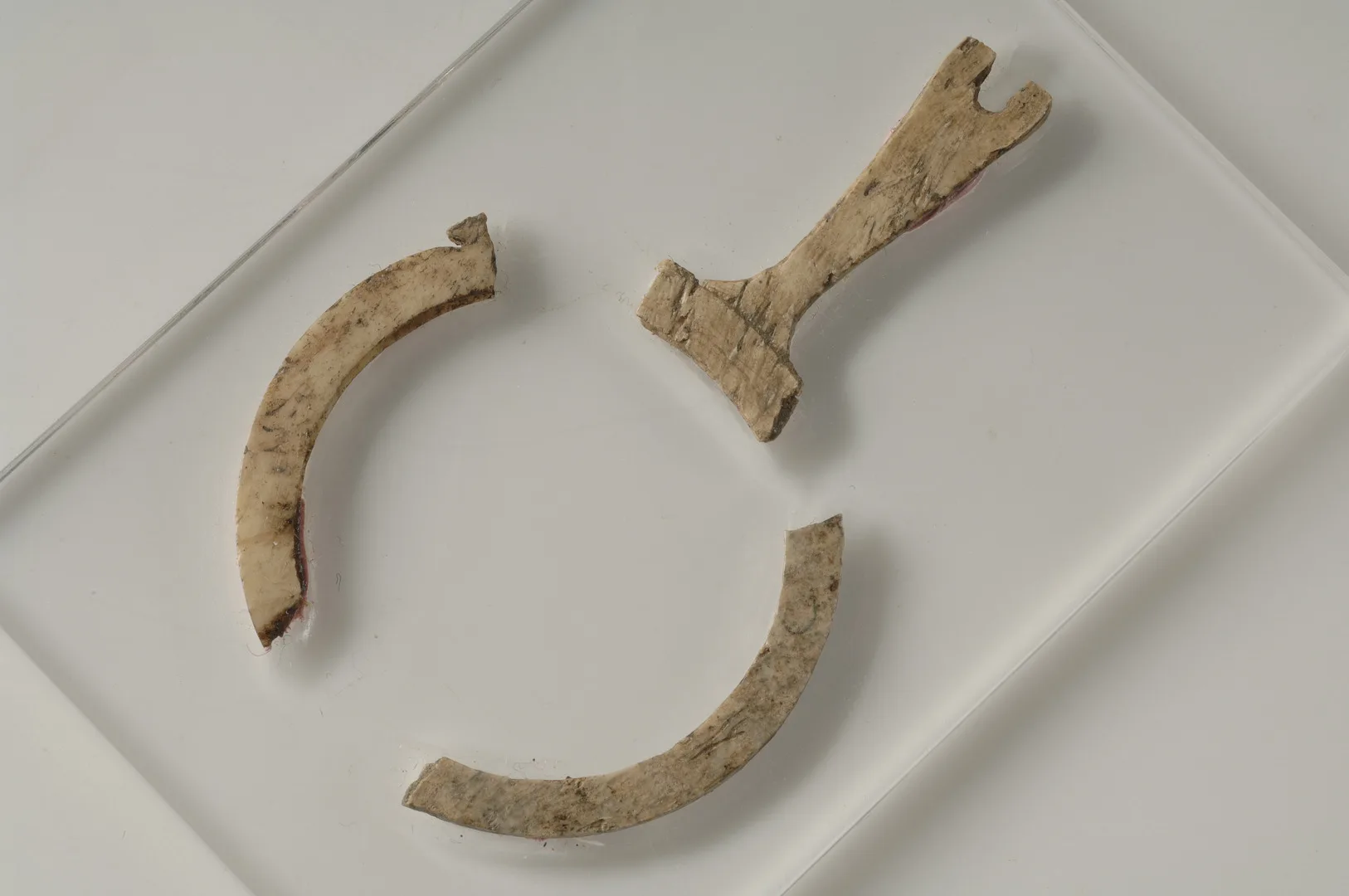

Spectacles

From Alvastra Abbey, Östergötland.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Medeltida liv

A surviving example from Alvastra Abbey in Östergötland consists of a fragmentary bone frame. Early spectacles lacked side-pieces and were designed to rest on the nose. The preserved frame represents one half of a pair; the lenses are missing. A second frame would originally have been attached with a rivet at the end of the shaft, hence the designation “rivet spectacles”. This construction allowed the circular lenses to be rotated outward so that they could grip the bridge of the nose. The design, however, required the wearer to remain relatively still, ideally seated in a slightly reclined position, in order to prevent the spectacles from falling.

Spectacles came to be regarded as symbols of learning and wisdom. In both medieval and later art, saints, scholars, and philosophers are frequently represented wearing them.

Initially, spectacles were intended only to assist those with presbyopia, and thus their principal function was to facilitate reading and writing. With the spread of printing in the 15th century and the subsequent proliferation of books, the demand for spectacles increased substantially, a development that has continued into the modern era.