Medieval professions and the feudal system

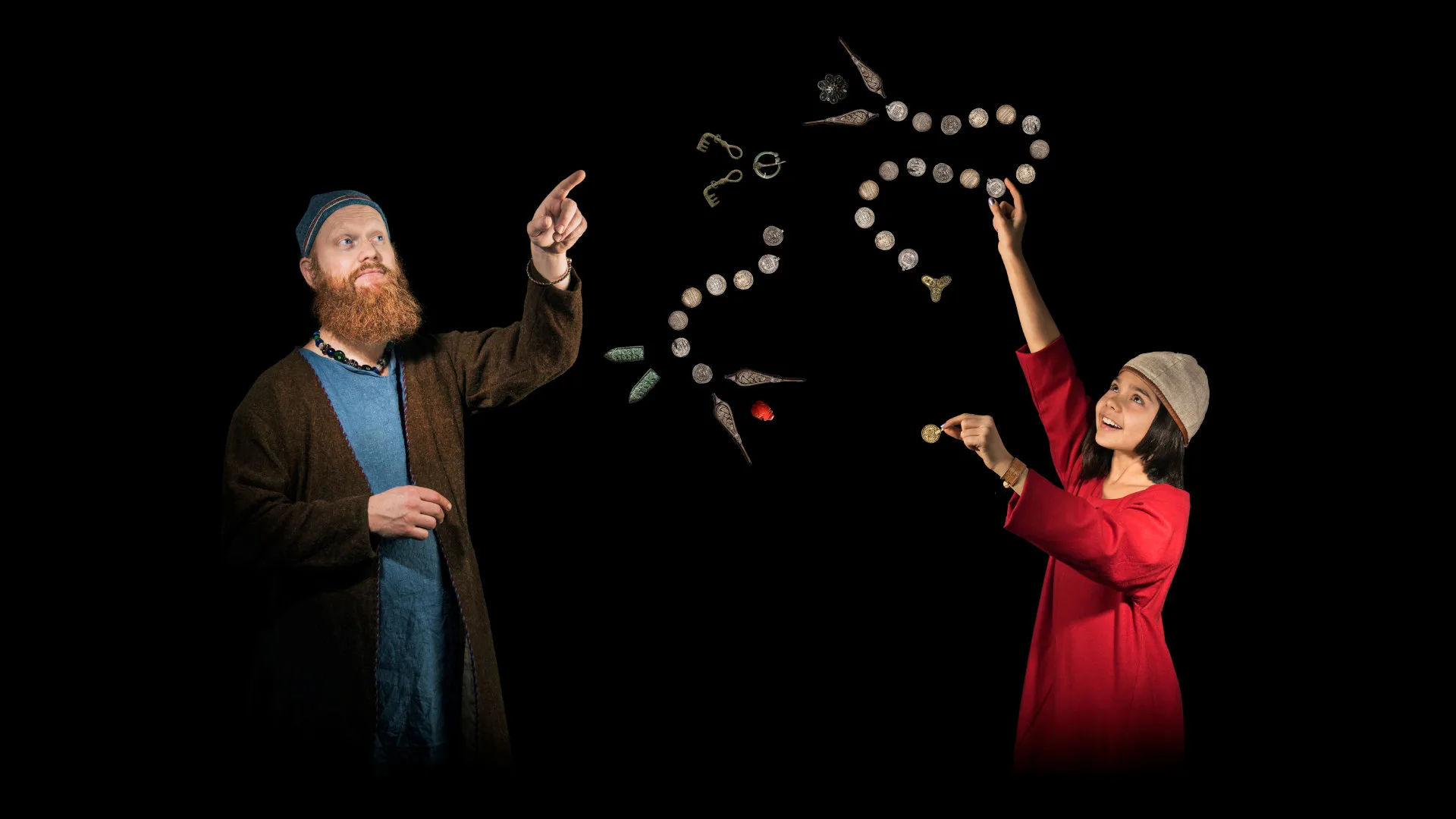

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Feudalism – like a pyramid

Feudalism was a system of governance that existed in Europe during the Middle Ages, and also in places like ancient Rome and Japan. The term itself was coined after the medieval period. Feudalism functioned like a pyramid.

At the top stood the king, who owned vast tracts of land but could not defend them all himself. He therefore granted portions of land to others who supported him, particularly in times of war. These men were known as vassals. They managed the land and collected taxes from the peasants who lived there. A vassal could also pass on parts of his land to sub-vassals, who assisted him in the same way. The system was based on exchanging land (or other privileges) for service.

At the bottom of the feudal hierarchy were the peasants. They were essential, as they cultivated the food everyone depended on. However, they did not own the land themselves. To use the land, peasants had to pay a fee, sometimes by working for free on certain days, sometimes with food or money. Many peasants were serfs, meaning they were bound to the estate where they were born and were not permitted to move elsewhere.

The feudal system became unstable as more layers were added. Moreover, peasants occasionally rebelled. In Sweden, the feudal system was neither as rigid nor as clearly defined as in Western and Central Europe.

The society of estates

Historians divide medieval society into four estates: peasants, burghers, clergy, and the nobility.

Peasants formed the largest estate. By the end of the 13th century, Sweden had around half a million inhabitants, 90–95% of whom were engaged in farming and livestock rearing.

The burgher class initially consisted only of merchants and craftsmen living in towns. To live and work as a burgher required special permission from the king.

The clergy comprised powerful men and church leaders who supported the monarchy. They were exempt from paying taxes. In 1280, the king decreed that a nobleman could become a knight and be exempt from taxation if he provided military service with armour, a warhorse, and soldiers. These noblemen were henceforth known as the aristocracy (the secular nobility), distinct from the clergy (the spiritual nobility). Thus, the three estates became four.

This division into four estates became more formalised towards the end of the Middle Ages, when representatives of both the higher estates (nobility and clergy) and the lower (burghers and peasants) were summoned to so-called “diets” or estate assemblies, where the monarchy sought to anchor and gain support for political decisions among the broader population.

Burghers

Burghers engaged in crafts and trade, held a share in a town, known as “burghership”. Burghers were required to pay taxes to the town and participate in fire protection, night watch, and defence. They were also obliged to perform military service for the crown.

Many towns emerged during the Middle Ages. In present-day Sweden, 70 localities gained town status during this period. These growing urban centres required specialised professionals and craftsmen, as households no longer produced their own tools and implements. Shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths, and bakers are just a few of the new professions that arose. Merchants also played a significant role in the development of towns, engaging in the import and export of goods, particularly in port cities.

Peasants

The majority of the medieval population were peasants. Life as a peasant was often harsh. Poor weather could lead to failed harvests, resulting in hunger and heavy debts. Tenant farmers, who owned very small plots of land, were especially vulnerable.

More than half of Swedish peasants owned their land and farms outright. They paid taxes directly to the king and were known as “odal peasants”. To be an odal peasant, one had to have inherited the land over several generations. The other type of peasant worked land owned by the nobility. They paid rent to the landowner, often in the form of produce such as butter, meat, or bread. Hunting and fishing remained important for peasants. In many parts of the country, especially in Norrland, taxes were paid in the form of animal skins.

Self-owning peasants had to pay taxes to both the king and the church. They were therefore called “tax peasants”. The many levies imposed on peasants, along with the labour they were required to perform on others’ land, led to numerous peasant uprisings during the Middle Ages.

During the Middle Ages, it was the peasants who sustained the country. By the early 11th century, all fertile land in the plains of southern and central Sweden had already been cultivated, and farms were densely packed. However, more efficient farming methods and new tools led to rapid population growth and the spread of settlements into new areas. As early as before 1100, settled peasants could be found as far north as the Torne Valley. Rules for new cultivation were included in the provincial laws. For example, one could not claim land that someone else was already farming.

Craftsmen

To supply the growing urban population with food and tools, more specialised crafts emerged during the Middle Ages. Professions such as shoemakers, tailors, potters, and coppersmiths became common. Most crafts were organised into three levels: apprentice, journeyman, and master.

Masters belonged to guilds governed by specific laws called guild statutes. These statutes regulated meetings, procedures, and punishments for rule-breaking. Journeymen were paid workers who needed a master's permission to work but could change employers. Apprentices lived with their masters and were paid in food, lodging, and training.

Becoming a master required years of training, starting with 4 to 5 years as an apprentice, followed by a journeyman’s test. Few advanced beyond journeyman. Those who could afford it and had guild support could take a master’s test, apply for town citizenship, and join the guild.

Guilds also had social roles, supporting sick members, orphans, and widows. A master’s widow could inherit the workshop, one of few paths to female independence.

Were there doctors in the Middle Ages?

There were no doctors or healthcare systems as we know them today. Many died from disease and malnutrition. The plague and leprosy were especially feared. Women often died from childbirth fever. Local wise women or men provided remedies. Monasteries and charitable institutions like “Holy Spirit houses” cared for the sick, poor, and abandoned children. Wealthy burghers could receive care if they were elderly and unable to manage on their own.

Tailors and textile workers

Most people lived through subsistence farming, producing food and tools at home. Wool was spun into yarn using a spindle, later replaced by the spinning wheel. Women spun, wove, and sewed on farms, while male tailors dominated in towns and held respected positions.

Blacksmiths

Blacksmiths were highly regarded, making tools and weapons. Village smiths made everyday items and weapons, while farmers often had small forges. Travelling smiths also offered services. In towns, specialised smiths emerged: sword polishers, armourers, and knife makers.

Minstrels and court jesters

Performers were called minstrels or jesters. They had low status and few rights, often travelling between villages, playing instruments like flutes, fiddles, drums, and jaw harps in exchange for food.

Thieves and criminals

Being a thief was dangerous. There were no prisons; punishments included fines, flogging, or having an ear cut off. Some were executed. Others were declared outlaws, anyone could kill them without consequence. Outlaws lived hidden in forests, sometimes for life.

A thief with the Devil and an angel. Painting from Litslena church, Uppland. ID 9315314. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC-BY 4.0).

Work-life balance?

Medieval towns housed everyone from wealthy merchants to beggars. Most people lived on farms and practised self-sufficiency, producing food, clothes, and tools. Surplus goods were sold in towns to buy items they couldn’t produce.

In the late 13th century, rural trade was banned; all commerce had to occur in towns. This allowed the king to collect taxes and tolls. Merchants bought goods from farmers and craftsmen and sold imported items like wine, salt, spices, and fine fabrics. Weekly markets and annual fairs were key social and economic events.

Celebrations

In a society where hard work began early in life, festivals offered a break. People celebrated births, baptisms, churchings, engagements, weddings, funerals, and inheritance divisions, occasions to gather, eat, dance, and enjoy life.

Medieval jug

Glazed earthenware jug found in Kalmar harbour.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Medeltida liv