Medieval art: wooden sculptures

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

When Christianity arrived in Sweden, the country became not only ecclesiastically but also politically and socially integrated into Europe. The earlier native art style, Viking animal ornamentation, disappeared, as the Catholic Church regarded it as pagan. There were no local models for the wooden sculptures created for Sweden’s first Romanesque churches.

The art produced in the early Middle Ages was heavily influenced by Christian Europe. Adam of Bremen does mention three statues of Norse gods in the temple at Old Uppsala, but we have no idea what they looked like, or even if they truly existed.

Romanesque or Gothic?

In art history, wooden sculpture is generally classified into two styles: Romanesque and Gothic. In the Nordic region, the traditional dividing line between these styles is placed around the mid-13th century. Of course, this is an artificial distinction. No such clear boundary exists in reality, and the styles often overlap.

When examining ecclesiastical art, it’s important to remember that medieval church art in Sweden was never intended merely for decoration. It always served a religious purpose. The demand for images of saints and crucifixes must have been immense, as every church would have needed at least one crucifix, one Madonna, and eventually a depiction of its patron saint.

The Viklau Madonna

Wooden sculpture from Viklau, Gotland

Video: The Swedish History Museum/SHM.

Behind the scenes with the Viklau Aadonna

Pia Bengtsson Melin, Senior Curator at the Swedish History Museum, shares a fascinating discovery: a cavity in the Madonna’s head.

Wooden sculptures in the Church

Medieval wooden sculptures had designated places within the church interior, depending on their role in religious practice.

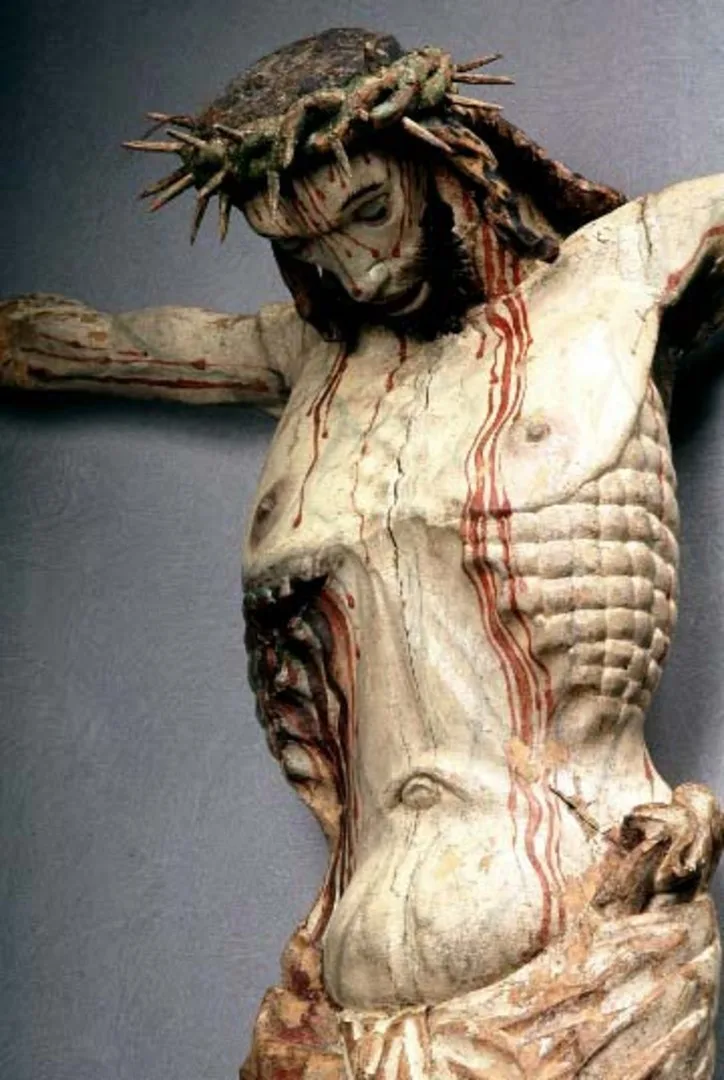

Between the chancel and the nave hung the triumphal crucifix. In addition to the high altar, churches often had two side altars: one dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the other to the church’s patron saint. The triumphal crucifix was suspended in the triumphal arch, the archway between the chancel and the nave. It was a large crucifix featuring a sculpture of the crucified Christ. The term “triumphal” refers to Christ’s victory over death through his crucifixion and resurrection on the third day. Besides the triumphal crucifix, there would also be a crucifix on the high altar and one or more processional crucifixes.

Sculpture of Christ

From Sorunda parish, Södermanland

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Sveriges historia

The Calvary group

Sometimes the triumphal crucifix was accompanied by additional sculptures placed in the triumphal arch. These are known as Calvary groups, a simplified version of the Crucifixion scene, typically featuring just three figures: Jesus on the cross in the centre, flanked by Mary and the disciple John.

Church interiors often included at least three altars. The high altar was always located in the eastern chancel. Two side altars were also common: one on the north wall, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and one on the south wall, dedicated to the church’s patron saint. In monastic churches, cathedrals, and larger urban churches, there could be many altars dedicated to various saints.

The Virgin Mary

By the time Sweden became Christian, the Virgin Mary had already attained a central role in the Catholic Church. It is likely that her image was present at the consecration of many early churches. The number of surviving wooden sculptures of Mary with the Christ Child is so great that we can reasonably assume every church acquired one as soon as it could afford to.

The sculpture of Mary, the Madonna, was placed on the northern side altar, to the left of the triumphal crucifix, which is to say on Christ’s right-hand side. The southern side altar held the church’s patron saint, who might also have given the church its name, for example, Saint Clare, Saint Nicholas, Saint Lawrence, Saint Stephen, and others.

The Mosjö Madonna

From Mosjö, Närke.