Medieval art: animals

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

People and animals lived side by side in the Middle Ages. By studying animal bones found at medieval settlement sites, we know which species coexisted with humans at that time. Most of the bones come from cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, horses, hens, and geese. Dogs and cats are also common finds.

From animals, people obtained both food and raw materials for tools and clothing. Animals also served as essential aids in daily life, as draught, pack, and riding animals. To own many different domestic animals was a sign of wealth.

Sheep

Like other livestock, sheep were smaller than today’s breeds. Mutton and lamb, as well as wool, were important products. Milk was also used, for example, in cheese-making. The lamb has long been a symbol of Christ as the bearer of humanity’s sins. In the Middle Ages, newly baptised children were often given a small wax tablet bearing the image of the Lamb of God (Agnus Dei).

Goat

In the Middle Ages, goats were most common in the countryside and far less so in towns. They were kept mainly for milk, butter, and cheese. The goat was sometimes called the “poor man’s cow”. A poor farmer who could not afford a cow had to make do with a goat for milk and meat. Goats also provided bones and hides that were used in handicrafts.

Pig

Domestic pigs were very similar to wild boar and were much smaller than modern pigs. In summer they roamed freely, feeding on beech mast and acorns. In towns, pigs were among the most common livestock, as they could live on household refuse. Domestic pigs were usually slaughtered young, and archaeological finds often include bones from piglets. The main slaughter took place in autumn, and the meat was preserved by drying, smoking, or salting.

Goose

Geese were common on medieval farms. Their meat and eggs were valuable, and their feathers were also put to use. Quill pens for writing were made from the wing feathers. The nib was cut broad, flat-ended and split, a form that later continued in steel and fountain pens.

Eating goose on Saint Martin’s Day comes from the legend of Saint Martin. The story tells how Martin, not wishing to become bishop, hid in a goose pen. The cackling of the geese gave him away. In anger, Martin decreed that geese should be slaughtered every year on 11 November.

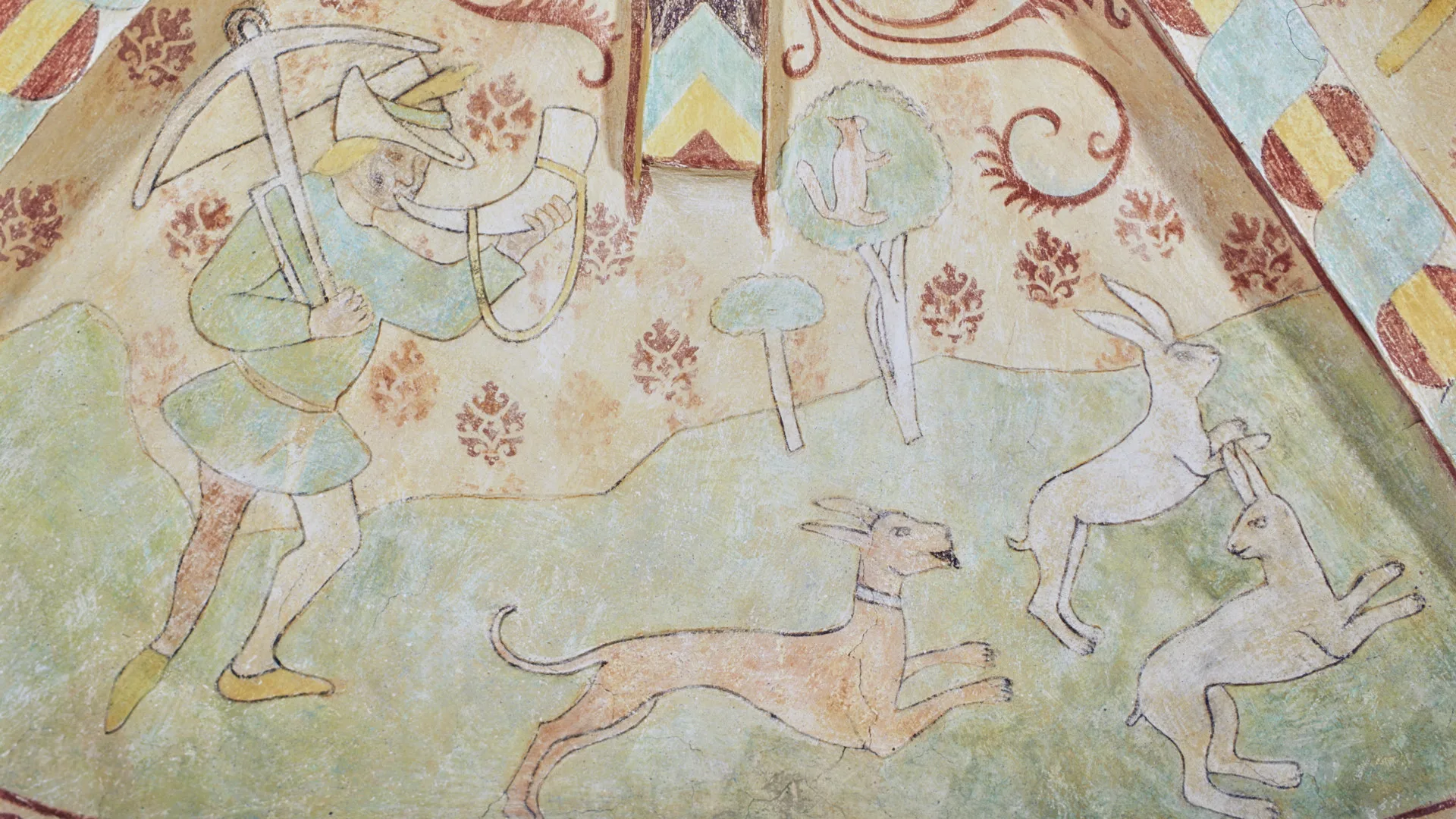

Painting from Tensta church, Uppland. ID 9413526. Photo: Lennart Karlsson/SHM (CC-BY 4.0)

Dog

The dog has been humankind’s companion for thousands of years. In the Middle Ages there were several different breeds. Greyhounds, mastiffs, hounds, and spaniel-like dogs were kept by princes and the wealthy nobility. In towns, smaller dogs were more common. On farms, sheepdogs, guard dogs, and hunting dogs were important domestic animals.

The dog’s significance is evident in medieval law texts, textbooks, and stories of saints and heroes. On the tomb slabs of crusaders, a greyhound is often depicted as a symbol of noble birth, speed, and courage. The dog also symbolises loyalty and marital fidelity.

Horse

Medieval horses were relatively small and sturdy, standing only about 130–135 centimetres at the withers. Their hides were coarser, and their tails and fetlocks more heavily haired. In appearance they resembled today’s Icelandic horses, Norwegian Fjord horses, and Finnish trotters. Horses were used mainly as riding and pack animals, but also as draught animals for wagons and ploughs.

Sweden exported large numbers of horses during the Middle Ages, so many that certain exports had to be banned, lest the supply become too scarce. To replenish stock, horses were imported from Spain, France, Flanders, and northern Germany. These horses were called Frisians and were considered the best riding horses because of their size and strength.

Painting from Dädesjö church, Småland. ID 9118012. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC-BY 4.0)

Hen

Hens were important in medieval households. Both meat and eggs were used, and eggshells are often found during excavations of settlements. The cock symbolised watchfulness, as he guarded his hens and warned them of approaching danger.

The cock was also thought to protect against lightning, since he always sought out the highest point on the farm. With his crowing he drove away the forces of evil and darkness. For this reason, a rooster often sits atop the highest church tower.

Painting from Vreda church, Småland. ID 9113808. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC-BY 4.0).

Cows and oxen

Cattle in the Middle Ages were much smaller than today’s. The withers height was only about one metre. From cattle, people obtained both milk and meat. Bones and hides were also used to make tools and clothing.

Oxen were also used as draught animals. In towns there were not enough animals to feed the population. Only property owners were allowed to keep cows, and only one each. Both rural and urban law codes contained strict provisions against illicit milking and the killing of animals.

Milking cows and churning butter

Milking was women’s work. Milk was used to make both butter and cheese. Butter was made using a churn: cream was pounded with a staff until lumps of butter formed. This is a common motif in paintings from medieval churches.

Women who had sworn themselves to the Devil, according to folklore, could be aided by a milk-hare that stole milk from the neighbour’s cow. With the stolen milk, the women, together with the Devil, could churn butter and build piles of butter. The milk-hare was a creature of fantasy, probably invented in years of famine when cows ran dry. In the picture you can see a woman churning butter with the Devil’s help.

Hunting wild animals

Alongside farming, hunting was an important source of livelihood. Landowners had the right to hunt and fish. Some forms of hunting, such as deer hunting, were reserved for the nobility. Peasants, on the other hand, were obliged to keep down predators, or they faced fines. The hunter’s main weapons were bow and spear, and he was aided by dogs that drove or retrieved the prey.

Traps were also widely used, often cleverly constructed. To prevent harm to people or livestock, traps were set out in autumn, when the grazing animals were no longer in the forest. In the picture you see a hunter on a hare hunt. He carries his crossbow over his shoulder and blows a hunting horn. A dog drives the hares, and behind him in the tree a squirrel can be glimpsed.