Baptism and exorcism in the Middle Ages

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

In medieval Sweden, baptisms were performed at a baptismal font, one of the most important sacred furnishings in the church. These fonts were often made of stone, and sometimes of wood. Many medieval fonts have survived to this day in churches and museums, and many are held in the collections of the Swedish History Museum.

A holy act by water

In Christian belief, baptism brings a person into the Christian Church and into the fellowship of believers. Baptism is a holy act, a sacrament. An infant who died at birth was lost if it had not been baptised, for the unbaptised could not enter heaven. Jesus himself was baptised in the River Jordan. In the earliest Christian times, people continued to be baptised in rivers and streams. Quite soon, however, dug-out pools or large wooden tubs began to be used instead. Up until the mid-13th century, it was preferred that the whole body be immersed in water at baptism, but gradually the practice shifted to pouring water over the head only.

The reason was the cold northern climate, which made it dangerous to chill the whole body. Infants sometimes died after being baptised in icy churches in winter. During the mission period in Sweden, from the mid-9th century until the 12th, both adults and children were baptised. Once Sweden was fully Christian, only infants were baptised.

The baptismal font

For most of the Middle Ages, the font, together with the altar, was the most important sacred furnishing in the church. It symbolised both the River Jordan, where Jesus was baptised, and the rock-hewn tomb from which he rose on Easter Day.

The font was placed near the entrance, for the unbaptised were heathens, and heathens could not be allowed too far into the church. To do so was thought to give free rein to dangerous powers to enter. Today, the font has been moved further into the church, usually into the chancel, since no one believes any longer that the little unbaptised child poses a threat.

Made by master masons

When a new church was to be built in the Middle Ages, large workshops and lodges were established around the building site. Many craftsmen were needed for such an extensive project, among them the makers of baptismal fonts, of whom only a few are known to us by name.

The vast majority of fonts are anonymous. Mårten the master mason made a large number of fonts found in Scania, five of them signed with runes. Tove, who carved the fonts in Gumlösa and Lyngsjö, was a very skilled stonecutter. Another known mason was Sigraf, whose fonts are found in several Swedish provinces, from Hälsingland down to Scania.

Artistically, however, the most significant is the so-called Tryde Master. The font at Tryde in Scania is among the most remarkable works of art of its kind. The Tryde Master also worked on Gotland, where several of his fonts remain in the island’s churches.

The material used for baptismal fonts

Of the stone types used for fonts, sandstone and limestone were most common, as these were easiest to work. On Gotland both sandstone and limestone were used, as in Scania. The people of Gotland exported fonts of these stones throughout the Baltic region.

In western Sweden, for example Bohuslän and Dalsland, soapstone was common. In Denmark, the hard granite was used. Fonts were occasionally made of wood, though rarely. In Sweden there are a few surviving wooden fonts, among them a pine font from Alnö Church in Medelpad.

The parts of a font

Stone fonts usually consist of two parts: a base and a bowl (known as a cuppa). Sometimes a middle section or shaft is also present. The varying shapes of the bowls were linked to the way baptisms were performed. When full immersion was required, a deep bowl was necessary. Where the bowl was too shallow, immersion had to be supplemented or replaced by the priest pouring or sprinkling water over the child.

Some fonts contain a drainage hole. Baptismal water was holy and could not be disposed of like ordinary water. The water in the font was therefore not emptied very often between baptisms, as this meant consecrating fresh water. By letting it out through the drainage hole, the water ran down through the base of the font into the consecrated earth beneath the church.

Because the baptismal water often remained in the font for long periods, it was covered with a lid to protect it from falling dirt. Such lids could be so heavy that a special hoisting device was needed to remove them. The lid also prevented theft of the power-laden water, which was sought after in magical contexts.

Images, symbols, and decoration

Medieval fonts are often richly decorated. Scenes from the lives of Jesus and the Virgin Mary are common. Many fonts also display ornamental designs, such as plant and animal motifs, which often carried symbolic meaning.

In Romanesque image cycles, the stories of Christ’s childhood often end with his baptism. These images explained the meaning and importance of baptism. The most significant scene, of course, is Jesus’ own baptism in the River Jordan. This motif appears on some of the oldest fonts, for example at Dalby in Scania, where John the Baptist is shown baptising Jesus in the river, while a dove descends from heaven. The dove became the general symbol of baptism, representing the Holy Spirit.

Many fonts also show scenes from the life of Mary. One is the Annunciation, in which the archangel Gabriel tells Mary that she will give birth to Jesus, the Son of God. Another is the visit of the three Magi, bringing their gifts to the infant Jesus in the stable.

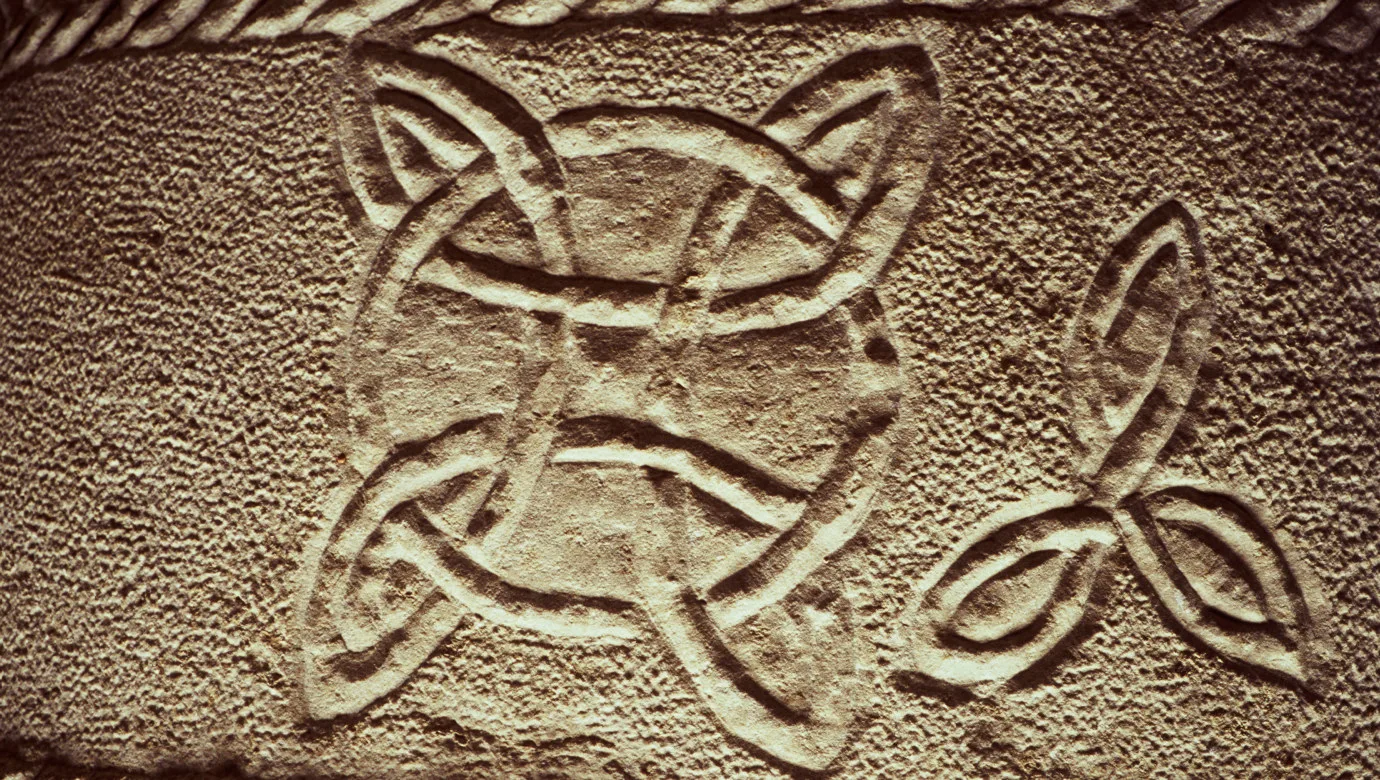

Bands and knots to ward off evil

Besides biblical figures and stories, other symbols also appear on fonts. Knotted bands, so common in medieval art, go far back in history. The significance of bands and knots has been profound across cultures and throughout time.

They are symbols of averting evil, of binding it. Many such signs were taken over by Christianity, and became important protective symbols against evil forces, including on baptismal fonts. Their decorative quality also made them attractive for artistic use.

Triquetra, tetragram, and pentagram

Among the knotted motifs are the triquetra, with its three pointed loops. Often seen as a symbol of the Trinity, it predates Christianity in the Nordic region.

The tetragram, also called Saint John’s Cross, associated with John the Baptist, also has ancient roots and appears for example on Gotlandic picture stones. This too was a symbol to ward off evil.

Finally, the pentagram, a five-pointed star, served as a protective sign against the Devil, demons, and witches. In ethnographic records it is referred to by various names such as trollfot (troll’s foot), markors (mare's cross), älvkors (elf’s cross), häxlås (witch’s lock), and more.

Symbolic animals

Fonts also feature animals, each with symbolic meaning. Examples include the pig (lust), lion (always strength, but representing either good or evil), dragon (the Devil), bear (wrath, counted as a sin), hare (shame), he-goat (in folk belief the Devil bore a goat’s beard, horns, and hooves – compare the Swedish word horbock, “old goat”), and other “unclean” animals as expressions of exorcism.

Exorcism is the casting out of evil spirits. At baptism, little devils were thought to leave the baptised child. The demonic forces, the beasts, are usually shown on the base beneath the font, while the saving baptismal water lies above.

By studying the material, form, technique, and decoration of baptismal fonts, one can often determine their age and place of origin. Sometimes fonts are so similar that they may be thought to have been made in the same workshop.