When Sweden became Sweden

Swedish rulers and monarchs – the complete list

The rulers we know most about are those who have been widely written about. The practice of numbering monarchs as Oscar I, Oscar II, and so on was introduced by Gustav Vasa’s son, Erik XIV. He chose his number by counting many royal predecessors who today belong more to the world of legends than to history.

It is difficult to say exactly when Sweden became a country. The answer depends on what we mean by the word country. Today we usually think of a country as a self-governing territory bound together by, for example, a common legal system and recognised as a state by other countries. At the end of the Viking Age and the beginning of the 11th century, Sweden did not yet exist in that sense. But even at that time, a realm that would eventually become Sweden had begun to take shape.

An important part of this process was Sweden’s conversion to Christianity. In the Middle Ages religion and politics were closely intertwined, and by becoming Christian, kings could be acknowledged by their peers in Christian Europe as well as by the Pope in Rome. Non-Christians were at that time regarded as legitimate targets for violent expansion, and by the late 11th century they could even be subjected to so-called crusades.

Olof Skötkonung

The first Christian king of Sweden is generally considered to have been Olof Skötkonung. Olof was baptised, had Sweden’s first coins minted, and was the first ruler to claim authority over both the Mälar Valley and Götaland. Strictly speaking, Olof was not king of a united Sweden, but his reign was nonetheless an important step towards the lands he ruled beginning to be regarded as belonging to one single country.

Coin stamped with Olof Skötkonung's image

Swedish silver coin, minted c. 995 in Sigtuna. Image of Olof Skötkonung (c. 995–1022). On the obverse the text 'ULAVAS REX SVENO' (Olof, King of the Swedes) and on the reverse 'IN NOMINE DNI MC' (In the name of the Lord, Creator of the World). Found at Digeråkra, Gotland.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Vikingarnas världFind this object in display 91, Vikingarnas värld Monter 91

By the late 12th century, Sweden consisted of Svealand, Götaland, and the southern parts of the Norrland coast. The realm was divided into provinces, each with its own laws. The areas we now call Skåne, Halland and Blekinge belonged to Denmark, while Härjedalen and Jämtland were Norwegian provinces. A significant step in clarifying the borders between the Scandinavian kingdoms was the establishment of new archbishoprics in the three realms. Uppsala was made the seat of a Swedish archbishopric in 1164, and Sweden thus became an independent ecclesiastical province, which strengthened the idea of the country as a distinct and unified entity.

At this time, two powerful dynasties were competing for the throne: the House of Sverker from Östergötland and the House of Erik from Västergötland. In 1250 King Erik Eriksson, known as the Lisp and Lame, died, bringing the House of Erik to an end. Under the three rulers who followed – Birger Jarl, Valdemar, and Magnus Ladulås – major changes took place that strengthened royal power. Tax collection became more efficient, and each province’s laws were written down. There was still, however, no single legal code for the entire realm.

The political centre of the country was now the Mälar Valley. Stockholm was founded in 1252 and quickly grew into the kingdom’s largest city. During the 12th and 13th centuries, Finland was conquered and Christianised through three crusades. Finland remained part of Sweden until 1809, when it was seized by Russia.

Part of a seal belonging to Magnus Ladulås

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Sveriges historia

Magnus Eriksson

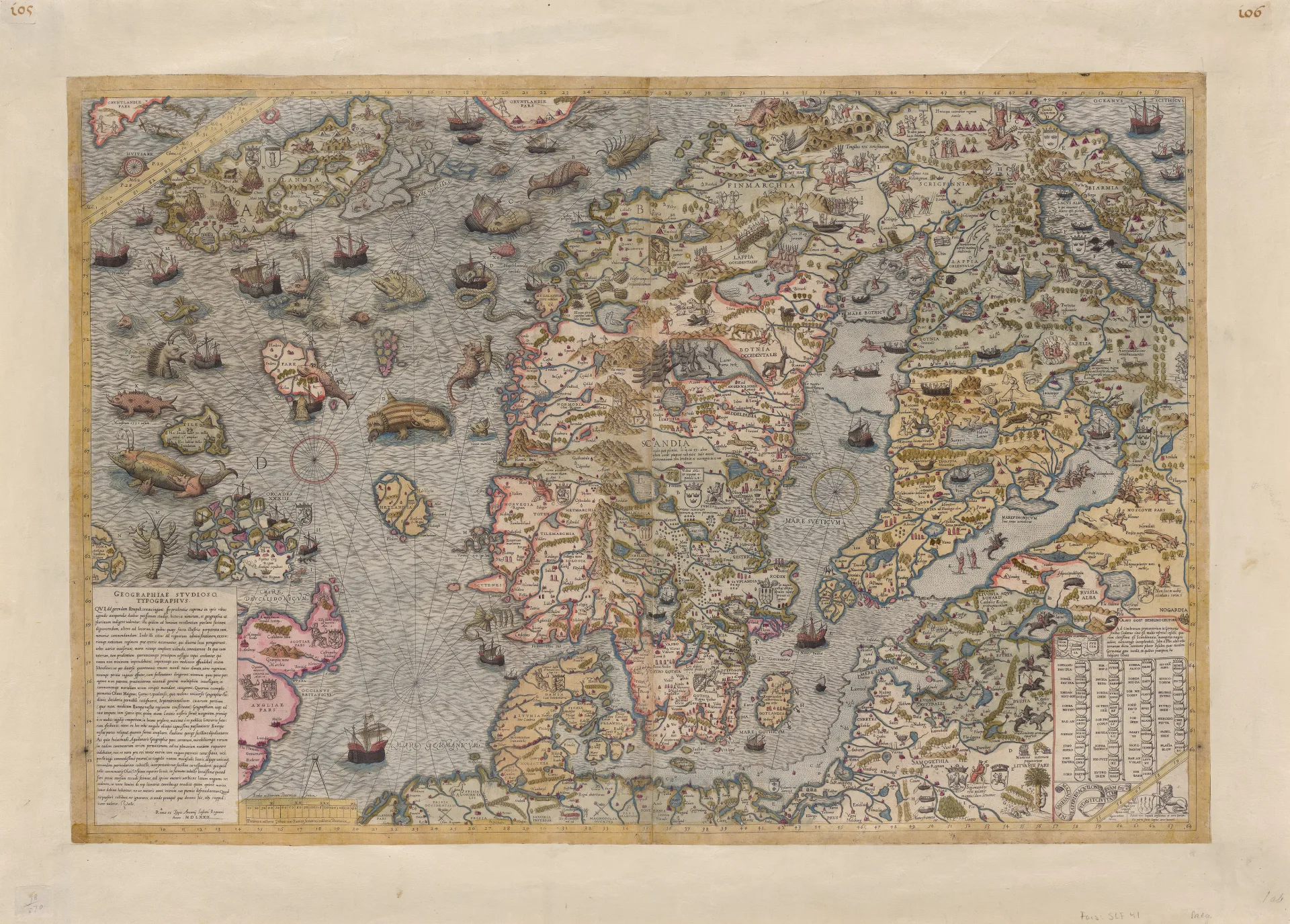

No Swedish king has ever ruled over a larger realm than Magnus Eriksson. It stretched from Karelia in the east to Greenland in the west, and from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Sound in the south. He inherited Norway and Iceland. Magnus was only three years old when he inherited the crown, so a regency governed until he came of age. Even so, his early reign was a success, bringing many reforms that benefited the peasantry.

In 1335 King Magnus abolished serfdom. It was no longer permitted to keep people as slaves. In 1350 the old provincial laws were replaced by a single law code for the whole kingdom: Magnus Eriksson’s Law of the Realm. At the same time, a separate law for the towns was introduced.

Silver crown

Found in Småland.

A time of unrest

Then came the plague, or the black death, and many died. As a result, the state collected less tax. King Magnus Eriksson and the magnates fell into conflict over how the kingdom’s finances should be used. This marked the beginning of a long power struggle between the monarchy and the aristocracy in Sweden.

The magnates rebelled, and Magnus Eriksson was deposed and restored to power several times. This weakened the country, and in 1360 the Danish king Valdemar Atterdag reconquered Skåne, Halland and Blekinge. The following year, the Danes invaded and plundered Öland and Gotland as well.

In 1363 the royal houses of Sweden–Norway and Denmark were united by the marriage of Magnus’s son Håkon and Valdemar Atterdag’s daughter Margaret. The Swedish magnates at first opposed this and instead wanted Magnus Eriksson’s nephew, the German prince Albert of Mecklenburg, to be chosen as king.

King Albert was supported by the North German towns of the Hanseatic League, a powerful trading alliance. When he moved to Sweden, he granted German nobles and merchants high offices and considerable influence. Many royal castles came under German lords, and Swedish towns were dominated by the Hanseatic League, which now controlled the Baltic Sea. Meanwhile Albert continued to wage war against the deposed Magnus Eriksson and his supporters in Norway. These wars drained the royal treasury, and the people had to bear the cost through increased taxation.