Venetian glass from Läckö Castle

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

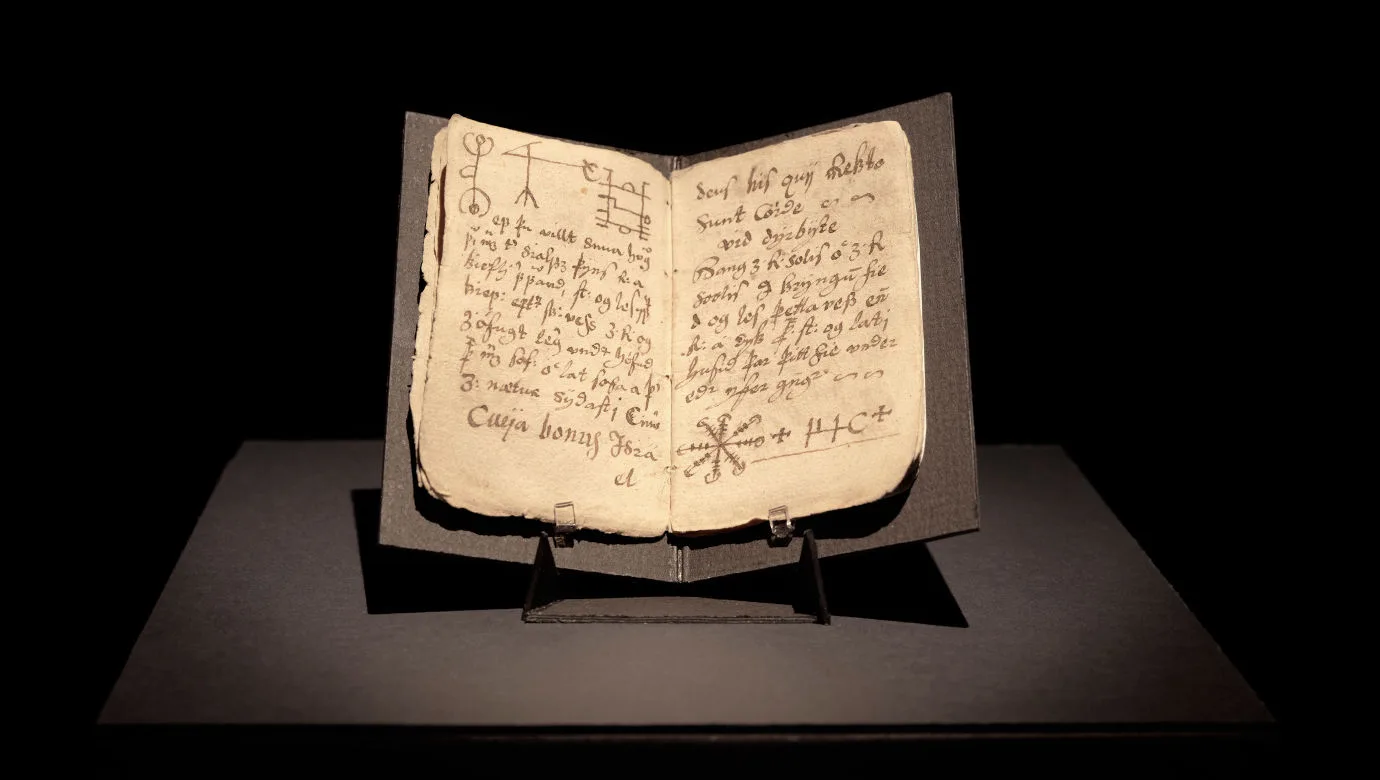

Glass is both hard and fragile. Despite its tendency to shatter, several exquisite pieces from earlier centuries have survived. Have you ever felt the urge to hurl a beautiful glass to the floor just to watch it explode into a thousand fragments? To experience the fleeting nature of this marvellous material, which uniquely combines hardness and fragility? If so, you're simply following an age-old tradition. As early as the first half of the 16th century, Olaus Magnus wrote:

Glass is either not used at all or only extremely rarely at the tables of northerners.

This was, he claimed, because northerners...

...take great delight in smashing glasses, whose shards can, by slicing tendons, cause not only irreversible injury to an arm but instant death. Such danger does not exist with mugs made of fir wood.

Despite these apparent dangers, the glasses in the picture were discovered during major archaeological investigations at Läckö Castle in the 1920s and ’30s.

Among the finds were at least two wine goblets, produced in Venice in the late 16th or early 17th century. Made of clear glass using a technique called filigrana, they were intended for serving red wine. The colour of the wine highlighs the contrast between the transparent glass and the embedded white glass threads.

Filigrana glass is often referred to as the aristocracy of glassware. It is made from clear glass interwoven with delicate threads, typically white, that form graceful patterns or intricate lattices. The process involves assembling rods of coloured and clear glass, melting them into a cylinder, and twisting it so that the threads spiral through the material. The technique was developed on Murano in the 16th century.

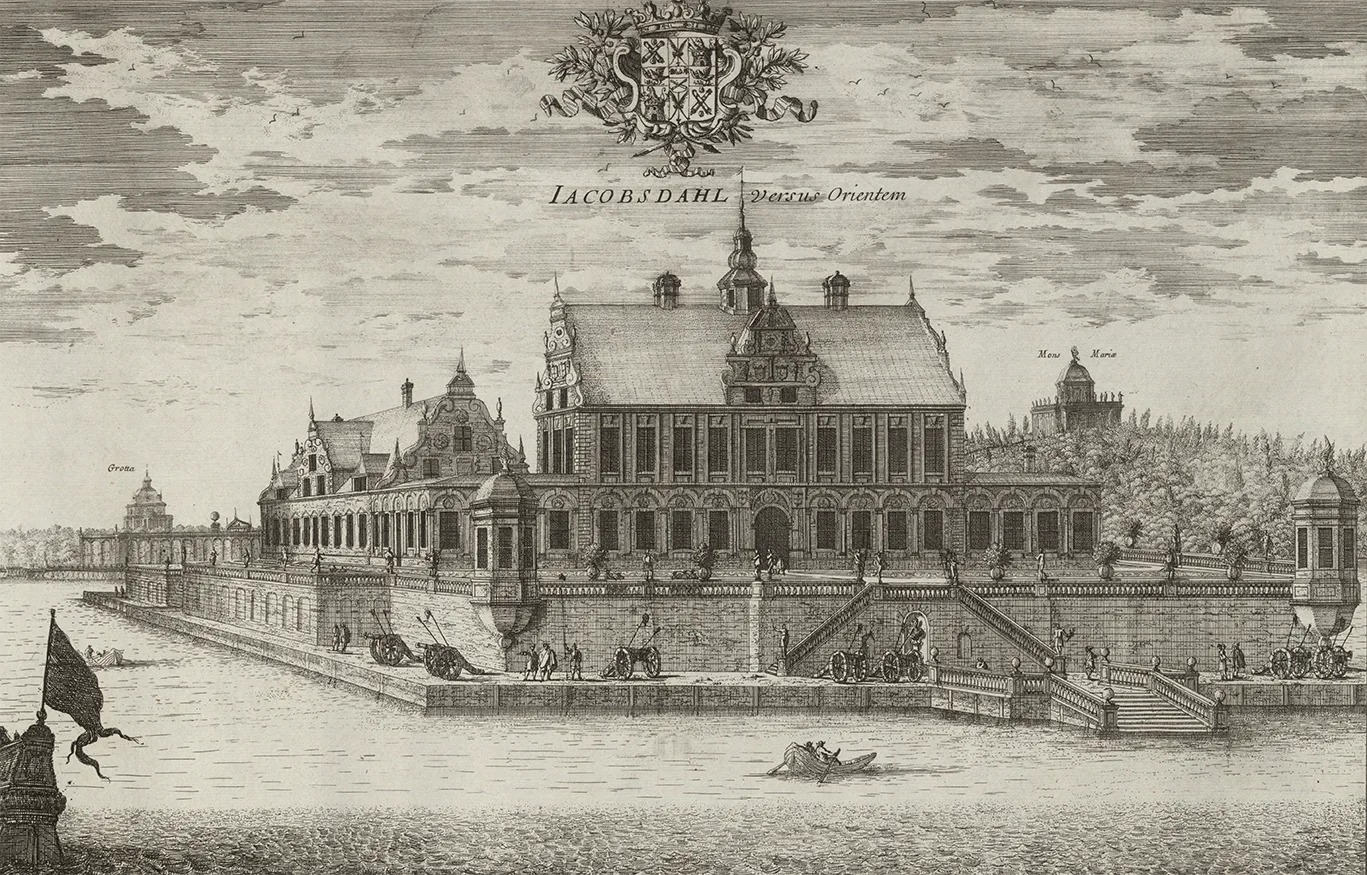

At the time these glasses were in use, Läckö Castle belonged to various noble families, including Jacob Pontus De la Gardie. These were people with strong connections to the rest of Europe, well aware of the shifting trends of continental fashion, not only in clothing, but also in the decorative arts.

Jacob de la Gardie

Unknown artist, 17th century. In the collections of Skokloster Castle.

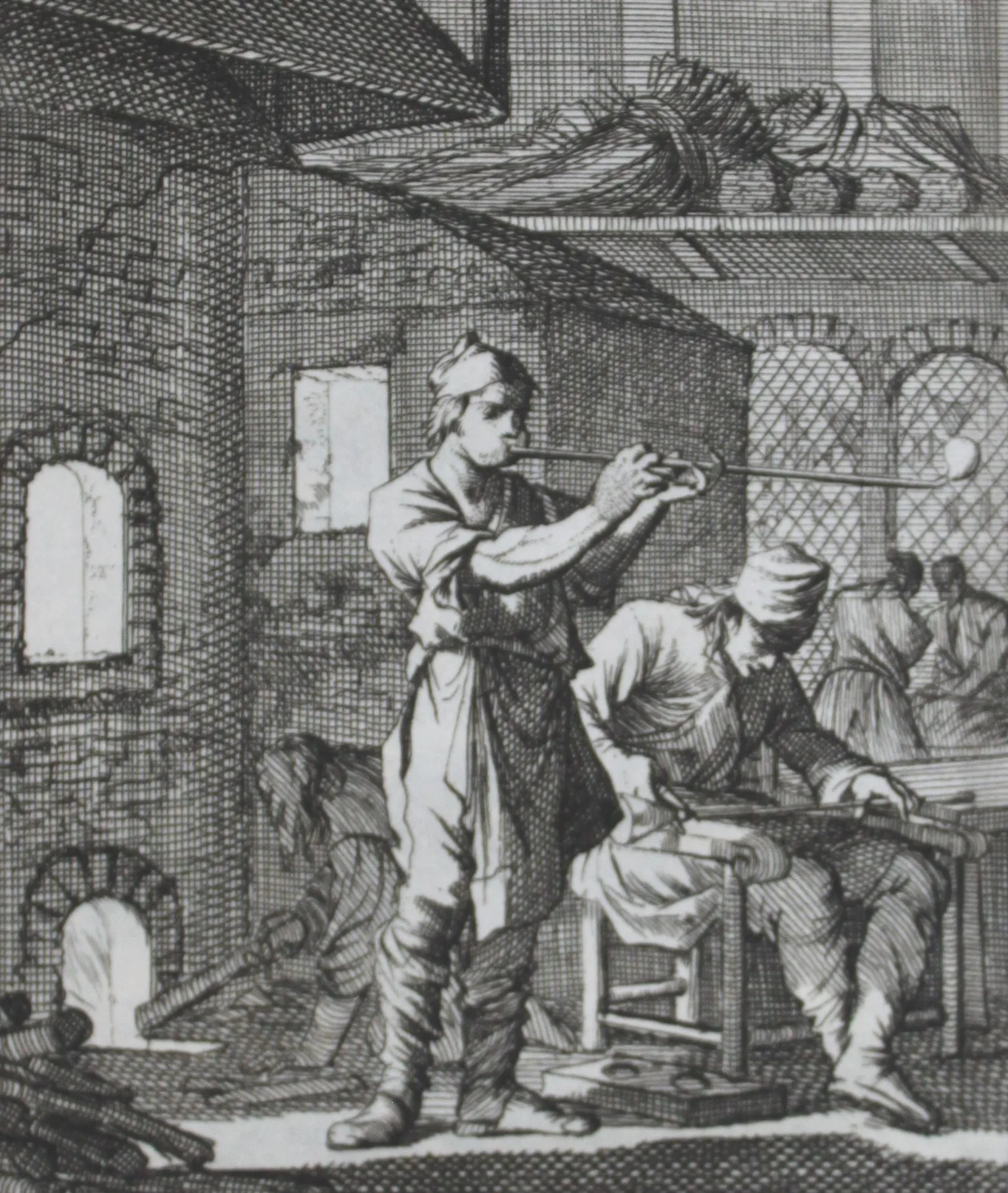

Venetian glassmaking

Venetian glass has a long and storied tradition. When the Läckö glasses were made, glass production in Venice had reached its peak in terms of technical skill, quality, and design. Venetian glass was a luxury item, highly fashionable and in great demand. The pieces were blown on the island of Murano, just off Venice, where glassmaking had been moved as early as the 1290s. There were two reasons for this: first, to remove a fire hazard from the city, and second, to keep tight control over the craft.

That control was necessary because the clear glass blown on Murano couldn’t be produced anywhere else in Europe at the time. The glass was a highly sought-after commodity, desired by kings and noblemen across the continent, and the trade was extremely lucrative. Despite intense surveillance on the island (escaping carried the death penalty), several glassblowers did manage to flee. With them, the secrets of clear glassmaking began to spread across Europe, leading to the establishment of glassworks in what is now the Netherlands, Germany, and England.

Venetian glass

Glass composition

Glass is made primarily from three components: a former, a flux, and a stabiliser. The former is typically silica, found in sand or quartz. The flux, which lowers the melting point, is usually potash or soda. The stabiliser, often lime, gives the glass its structure. When combined and heated to 1,000–1,500 degrees Celsius, the materials form a viscous, workable molten glass that can be blown, moulded, or spun into fine threads.

Glass can be either coloured or clear. Colouration may occur unintentionally through impurities or be introduced deliberately using various chemicals. Older glass often has a greenish tint due to iron oxide in the sand. This type is commonly referred to as waldglas or “forest glass”. If colour is intentional, several additives can be used: cobalt for blue, manganese for violet (and also to decolourise greenish forest glass), copper or gold for red, and selenium for soft reds or pinks.

Of the highest quality

At least two people at Läckö Castle once shared red wine, probably spiced to suit the taste of the time, from these supremely fine glasses, the very best money could buy. One hopes they appreciated the interplay between the red wine and the clear, white-threaded glass.

Perhaps they also felt the tension between fragility and strength, and in keeping with ancient tradition hurled the glass against a wall, watching it burst in a spectacular shower of shimmering shards.