Unna's stone

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

However, literacy was likely not widespread during the Iron Age. Society was primarily oral, with strong storytelling traditions. Nor could just anyone carve a runestone during the Viking Age, this was the work of specialised masters and workshops.

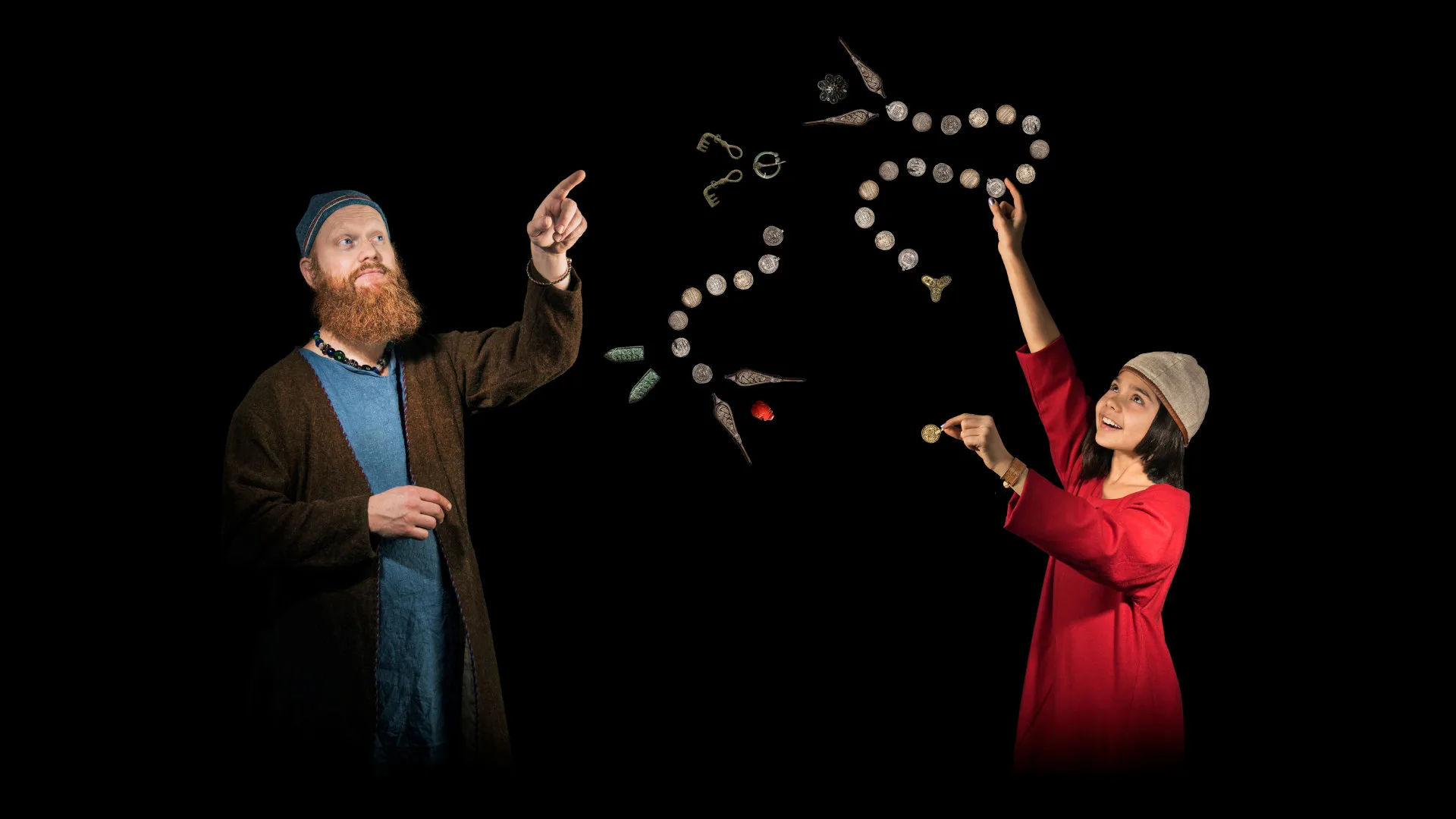

A woman commissioned a runestone

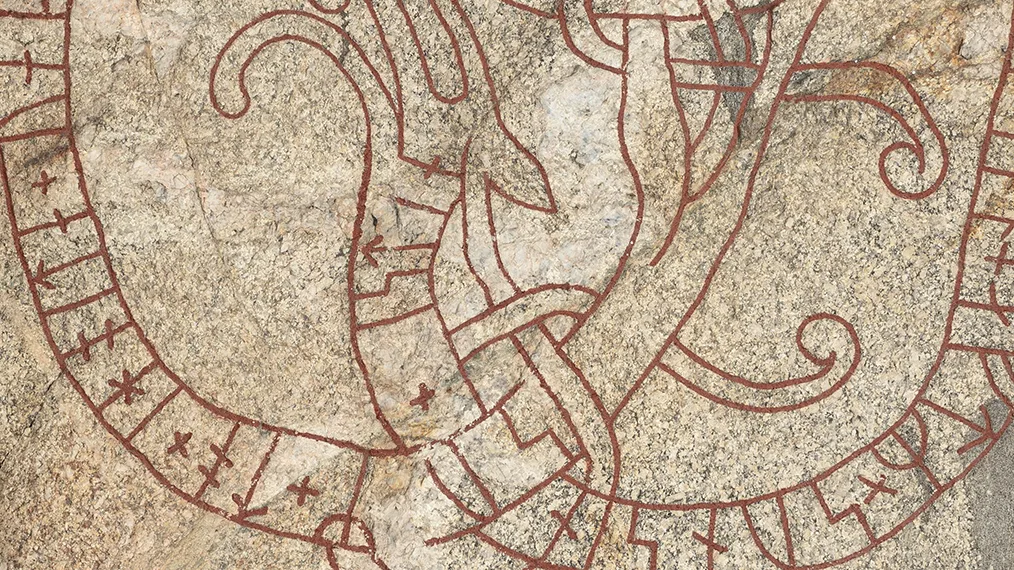

Sometime between AD 1050 and 1080, a woman named Unna had a runestone raised in memory of her son Östen. The dating is based on the ornamentation, as the style of serpent head in profile with a large eye was fashionable at that time.

The inscription reads:

Unna had this stone raised in memory of her son Östen, who died in white garments. May God help his soul.

That Östen died in white garments indicates he had been baptised, and it is clear that Unna was Christian. She commissioned a stone bearing a cross and concluded the inscription with a prayer.

Most runestones in Scandinavia were erected during the 11th century, and many are clearly Christian in character, featuring crosses and/or prayers.

Unna's stone

Runestone U 613 from Torsätra, Uppland.

Visäte carved the runestone

Unna’s runestone does not name the carver, although this is quite common on other stones.

Two of the most well-known signatures in the Mälaren region are Öpir and Fot, both active rune carvers during the latter half of the 11th century. By comparing signed and unsigned runestones, researchers have shown that many unsigned stones were carved by the same individuals who sometimes left their names.

In this way, scholars are fairly confident that the signature Visäte can be attributed to the carving of Unna’s stone.

Rune masters and craftsmen

Visäte was not alone in working on Unna’s stone around the mid-11th century. Recent research using laser scanning has revealed that multiple individuals were often involved in the creation of a single runic inscription.

Analyses show variations in carving techniques, indicating that behind each signature was a master supported by craftsmen and apprentices.

It appears to have functioned as a workshop, working on commission from people like Unna, those who could afford to have a runestone made. If a signature was included on the stone, it was, of course, the master’s name.