Two Icelandic books of black magic

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Both books are small enough to fit in a pocket and contain spells intended both to help and to harm. One is written on parchment, prepared animal skin, the other on paper. Judging by the handwriting, each book was compiled by at least two different individuals, suggesting they were shared or passed down through generations. The texts were written from the late 1500s through to the mid-1600s.

Black magic book

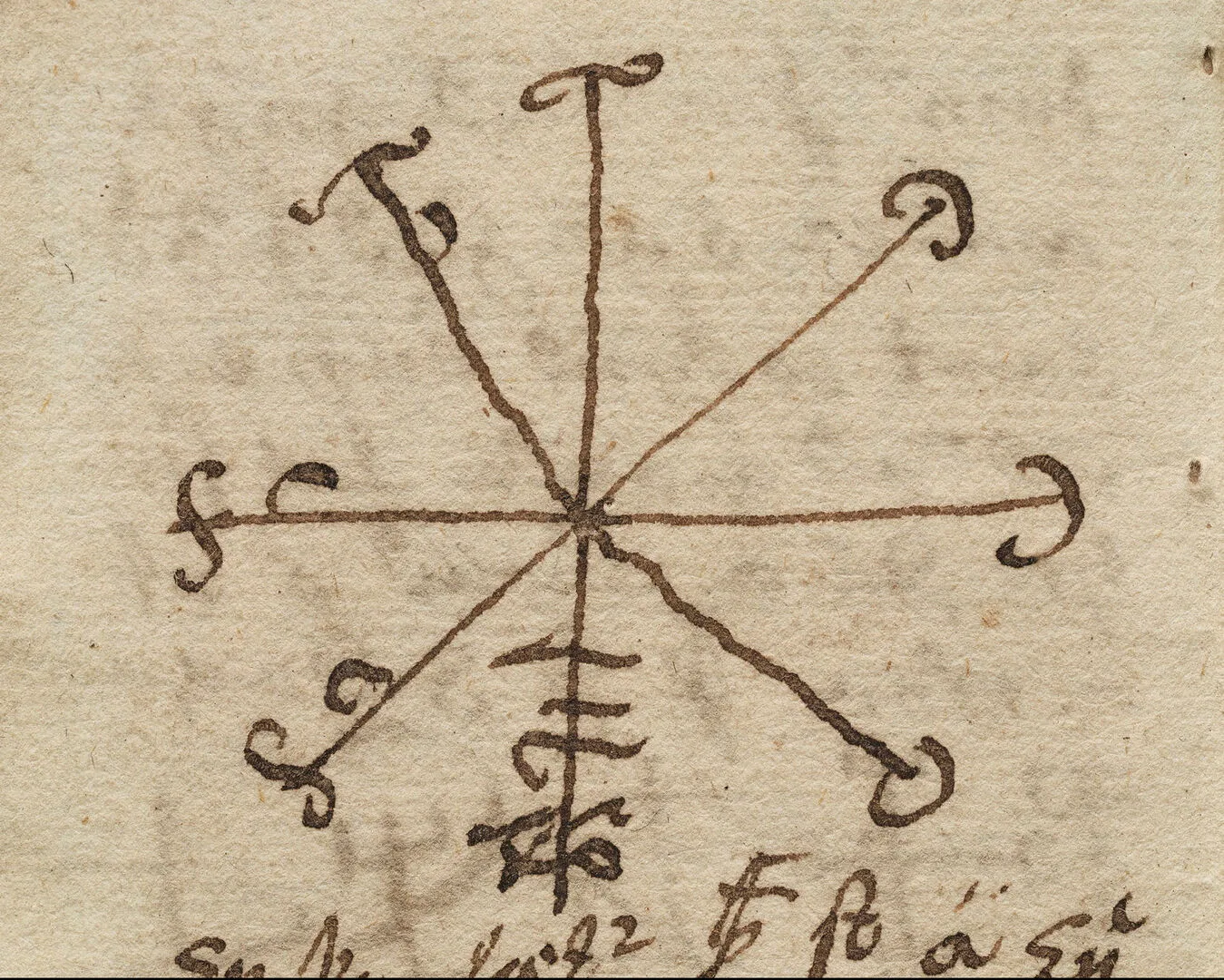

The stave (symbol) for good fortune in trade (kaupaloki) is visible on the right hand page.

These books reflect the belief that it was possible to influence the world through magic. White magic, or benevolent magic, was used to heal illness or protect against evil forces. This stood in contrast to black magic, maleficium, which involved summoning dark powers, often with the intent to harm.

The magic in these books is carried out using magical signs, or staves, known in Icelandic as galdrar, often accompanied by spoken or written incantations. Words, whether uttered aloud or recorded, were believed to hold great magical power.

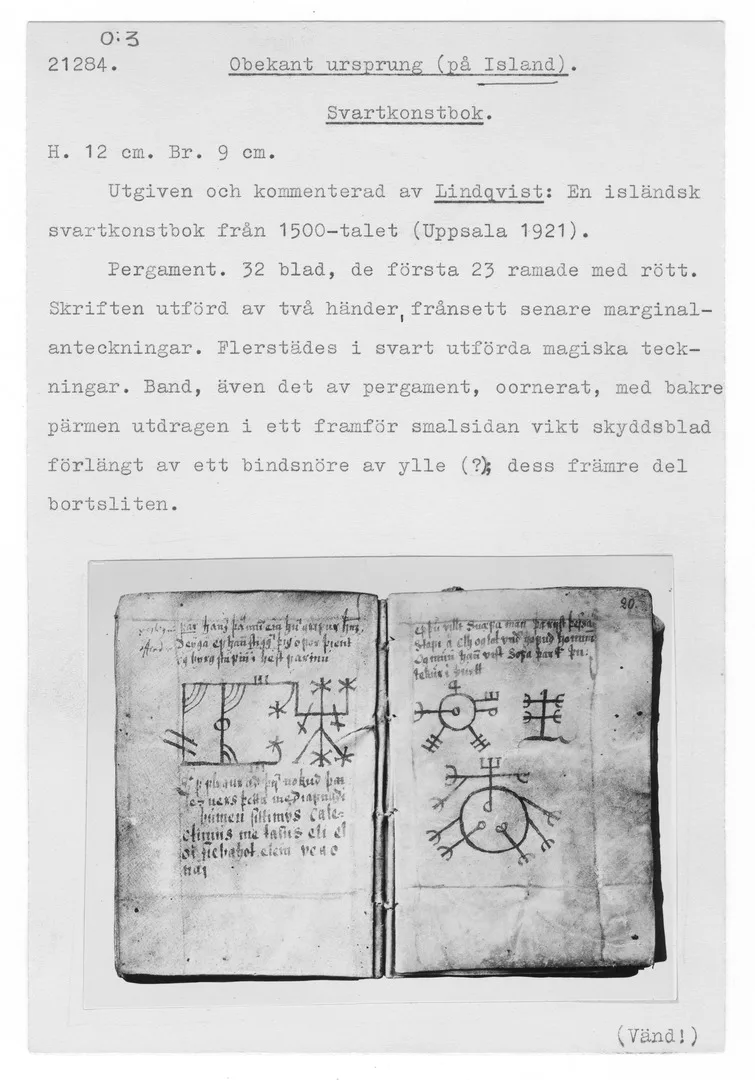

Book of black magic

Archival information about an Icelandic book of black magic.

To invoke the force behind the spells, the practitioner might call upon Jesus, God and the Holy Trinity, but also ancient Norse gods such as Odin. While Christian references dominate, the presence of older formulae and symbols suggests that the Norse pantheon was still part of people’s cultural consciousness well into the 16th and early 17th centuries.

Many of the magical staves, or galdrastafir, evolved from Norse runes. Their forms varied depending on their purpose. For instance, one galdr called Ægishjálmur (the “helm of awe”) was used for protection against evil and aggression; Vatnahlífir offered safety from water; and Kaupaloki ensured success in trade.

Magical stave

From an Icelandic book of black magic in the museum collections.

Runes to induce flatulence and helmets of invisibility

To increase the power of a symbol, it could be carved multiple times. Particularly potent was the ass-rune, associated with the god Æsir. In one spell from the book, this rune is inscribed eight times to cause severe abdominal discomfort, and uncontrollable flatulence, in an enemy:

I carve for you eight ass-runes, nine nauthiz-runes, thirteen thurisaz-runes, may they torment your belly with violent bloating and... unrelenting flatulence... may you never cease to break wind, day or night...

The black books include spells for everything from curing headaches, stopping bleeding and easing childbirth, to killing livestock, seducing women, inciting fear, and shielding oneself from the wrath of powerful men.

The staves could be carved on parchment, paper, wood, plates, even food. To cause vomiting in an enemy, you might inscribe the magical signs on cheese or fish and serve it to your victim:

He shall gain no benefit from that which he eats that day.

If instead you wish to become invisible by crafting an invisibility helmet, the procedure is as follows:

Take a hen’s egg and pour into it blood from the big toe of your left foot. Place the egg beneath a bird and let it be incubated. Once it hatches, burn the chick on oak wood. Place the ashes in a linen pouch and wear it on your head.

The witch hunts

One of the darker chapters in European history is the wave of witch hunts that swept the continent from the late Middle Ages through to the mid-1700s, costing thousands of lives. In the 17th century, this hysteria reached the Nordic countries.

In Iceland the most intense persecution took place between 1604 and 1720. At the time, Iceland was a struggling outpost under Danish rule, plagued by cold climate, famine, livestock deaths, and outbreaks of the plague. People searched for answers. Surely, they reasoned, such suffering must have been caused by evil acts.

In Iceland, the witch was a man

Historically, witchcraft accusations across Europe were overwhelmingly directed at women. Of the nearly 300 people executed for witchcraft in Sweden between 1668 and 1676, the vast majority were women.

Iceland, however, was an exception. The archetypal Icelandic witch was male. Of the 120 known trials, only nine were against women. Among the 22 people sentenced to be burned at the stake, just one was female. Why the difference?

In Iceland, magic was more strongly associated with literacy. It was seen as the domain of educated men. The boundary between scholarly learning and occult practice was often blurred, and magical texts were even studied at Icelandic universities. It is likely that the black books were written by men from this educated class. The inclusion of spells designed to enchant women and win their love suggests a male authorship.

The book’s journey from Iceland to Stockholm

To be caught with a book of black magic during the height of the witch hunts could mean a death sentence. Was this book smuggled out of Iceland during the persecutions? Or perhaps it was confiscated from someone condemned for sorcery?

What we do know for certain is that the book eventually made its way from Iceland to Copenhagen (then also Iceland’s royal capital). There, it was purchased in 1682 by the Swedish linguist and antiquarian Johan Gabriel Sparfwenfeld. It then travelled to Sweden, where it entered the collections of the Royal Academy of Letters and the Swedish History Museum, where it now rests in storage, quietly keeping its secrets.