The woman from Barum

Stone Age

12,000 BC – 1700 BC

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

We know that people lived in and moved through the region where her grave was found. Discoveries from the same period have been made during construction work, archaeological surveys, and a few excavations. When nearby Lake Råbelövssjön was lowered around the turn of the 20th century, a wealth of Stone Age finds was also uncovered.

How the Barum woman was found

Her discovery also came during fieldwork. In early summer 1939, farmer Oskar Larsson and farmhand Sven Eriksson were digging near the shore of Lake Oppmannasjön. Working with picks and crowbars in the lime-rich soil, Sven struck what turned out to be the skull of a human being.

The skull belonged to the Barum woman. Archaeologists excavated the grave. A larger area around her was also investigated, but no other burials were found. Because her skeleton was unusually well-preserved and clearly very old, it was decided she should be brought to the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm. She arrived there in November 1939, where she has remained ever since.

What the skeleton reveals

Samples from her skeleton have been radiocarbon dated to between 7010 and 6540 BC. Isotope analysis (carbon-13) has also been conducted to learn more about her protein intake. The results suggest she mainly consumed terrestrial animals and plants, with some possible contribution from freshwater sources.

However, distinguishing between freshwater and marine protein based solely on carbon-13 is difficult for this period, since the Baltic Sea had a low salt content at the time.

Based on pollen found on the skeleton, it is believed she was buried in spring. Her body was placed seated in a pit, legs drawn up, hands in front of her chest, with the body and face leaning forward.

The woman from Barum

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Grave goods

Two objects were found in the grave. The first is a hunting weapon, which initially led archaeologists to believe the skeleton was male. The object is a a type of composite tool called a slotted bone point. It consists of a sharp bone point, originally mounted on a shaft. Grooves had been carved along its sides, where tiny flint blades, called microblades. These were attached using resin, a material that functioned as a kind of Stone Age glue. The microblades were made from flint. The purpose of these blades was to inflict additional damage to the target.

Slotted bone point

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Reconstructing the bone point

At the time of excavation, only five microblades remained in their original positions. The others were found scattered in the surrounding soil. Today, the bone point has been reconstructed, and all the microblades have been reattached but several indications suggest that their current placement is not original. For example, the ridges of microblades are typically aligned upward on one side and downward on the other, which is not the case in the reconstruction.

Interestingly, the flint used in the microblades does not come from local Kristianstad flint in northeast Skåne, but from Senonian flint found in the southwest of Skåne. We don’t know whether this means that the Barum woman came from southwestern Skåne, or whether the weapon was produced there.

The choice of material may have signalled valuable contacts and exchange, or simply reflected a preference for the aesthetic or quality of Senonian flint. Four incised lines are also visible near the base of the point.

Position of the weapon in the grave

When the remains were was excavated, the weapon was found within her right chest area. Based on this position, photo documentation, and comparisons with similar graves, researchers believe the object was originally placed in her abdominal area, with the point angled toward her head.

The second grave object is a bone chisel. It shows signs of wear and may have had multiple uses, such as woodworking, hide processing, or digging. It was found beneath her left pelvic bone.

Bone chisel

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Man or woman?

A debate arose at the time of discovery: was the skeleton male or female? Archaeologists assumed it was a man because of the hunting weapon. But the osteologist, or bone expert, who first studied the bones identified the remains as female. While some skeletal features appear male, the majority are typically female.

Initially, the osteologist’s assessment was questioned. But in the 1970s, a re-analysis noted changes to the pubic bone, interpreted as evidence that she had given birth multiple times. This led to wider acceptance that the skeleton was female.

Today, we know that similar pelvic changes can result from other physical stresses and occur in both men and women. While it is possible that the Barum woman gave birth, this cannot be said with certainty.

We now also know of other Stone Age graves where women were buried with hunting and fishing tools, showing that both women and men participated in these activities.

Life in the time of the Barum woman

The Barum woman and her group lived a mobile lifestyle as hunter-fisher-gatherers, residing in huts or temporary shelters. In winter, they may have gathered in larger groups. They sought ways to preserve food: for example, in Norje Sunnansund, just 20 kilometres east of Barum, archaeologists have found a fermentation pit used to preserve large quantities of fish. This has prompted new ideas that people in Skåne at the time may have been more settled than previously thought.

The climate was a few degrees warmer than today, and the area was covered with forests of pine, birch, and hazel. Other deciduous trees such as oak, elm, ash, and linden were beginning to establish. The forests supported hunting of elk, red deer, roe deer, and wild boar. The area was also rich in plants, nuts, and berries.

Nearby wetlands and lakes such as Råbelövssjön, Oppmannasjön, and Ivösjön offered abundant fish and waterfowl. Lakes and waterways also served as transport routes.

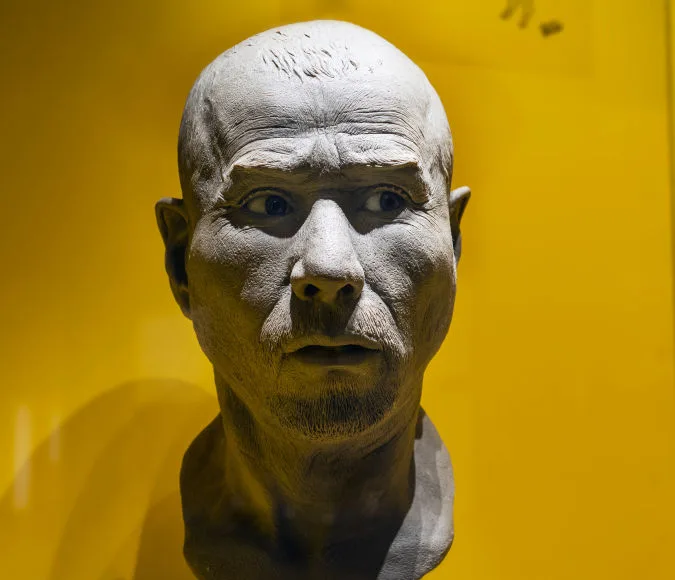

Osteological analysis shows that the Barum woman was 151 centimetres tall, slenderly built, and between 40 and 50 years old at the time of her death. A facial reconstruction has been created based on her skull.

The Barum woman in the exhibition Prehistories

Today, her skeleton is on display in the exhibition Prehistories at the Swedish History Museum. However, it is shown in a more upright and reclined position than how she was likely originally buried. No attempt has been made to place the grave goods in their original locations, instead, they are positioned at the front of the display case for easier viewing.