The Virgin Mary in medieval art

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Two examples of objects featuring the Virgin Mary are the engagement ring of King Gustav Vasa’s parents and the Edshult Madonna. After a long search, the latter can now be seen at the Swedish History Museum.

During the Middle Ages, Sweden was a Catholic country where the Virgin Mary held a special place. She was the one closest to Christ. Almost every church had an altar in Mary’s honor with a sculpture or altarpiece depicting her. The cult of Mary was significant not only in churches but also appeared on everyday objects.

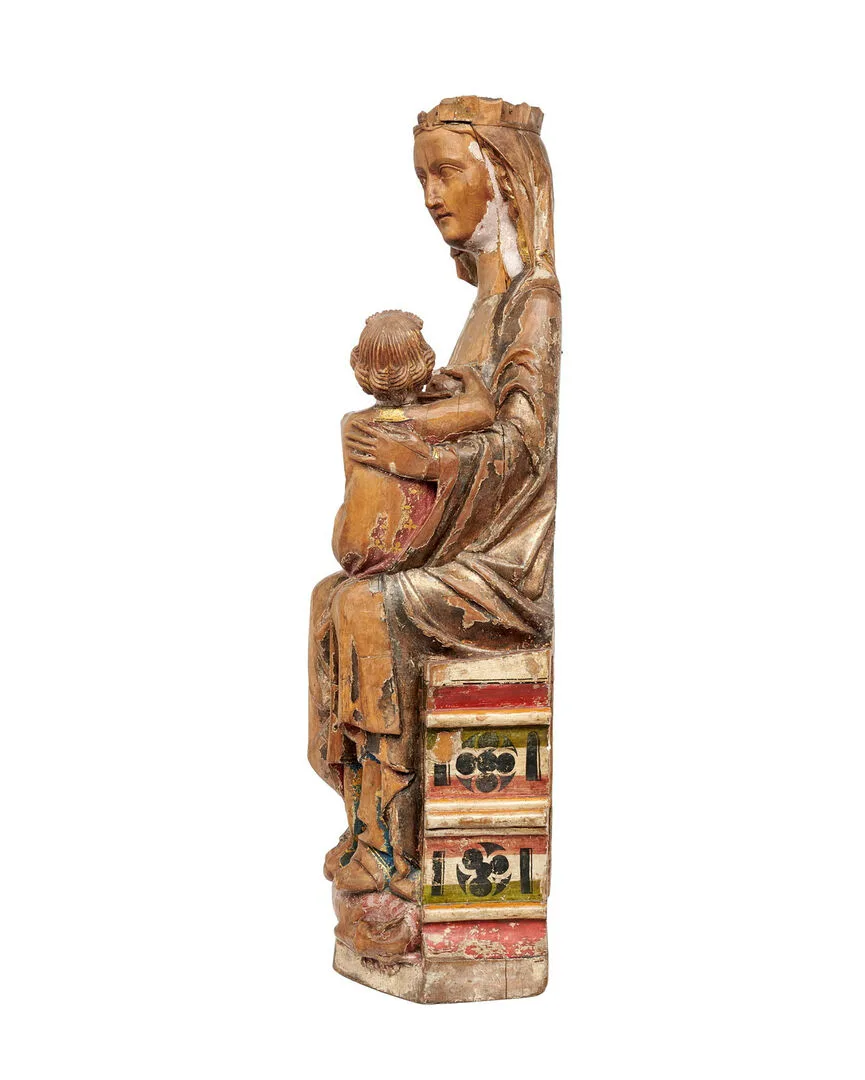

The Madonna from Edshult

One of the Swedish History Museum’s most beautiful depictions of Mary is the Madonna from Edshult Church in Småland. The Virgin Mary, holding the Christ Child, is usually portrayed as a young girl. But Mary from Edshult is truly a heavenly queen; serious, almost a little haughty, she sits to nurse her child.

The Madonna from Edshult

During the 12th century, the Christ Child was often depicted rigidly as a little king in Mary’s lap. But when this sculpture was created, in the early 14th century, artists had begun to show interaction and tenderness between mother and child. She offers her left breast to him, and he looks up at her face, placing one hand on her arm and the other on her chest. Mary gazes far beyond his head, perhaps thinking of his fate.

Original colors

The sculpture was once painted. Although some of the paint has been lost, enough remains to imagine how magnificent it once was. Beneath her golden crown, Mary wears a white veil with red stripes. She is dressed in a light blue gown with gold patterns, cinched at the waist with a belt decorated with gold roses. The hem has a finely patterned border. The neckline was likely trimmed with a stiff gold-embroidered band.

Original paint details

On the Madonna from Edshult

Over her gown, she wears a golden cloak with red lining. The Christ Child wears a purple garment decorated with gold leaf patterns, with gold trims at the neck and hem. Mary sits on a bench painted red and green, and the black ornaments on the ends likely represent carved details of the bench.

Mary rests her feet on a pink dragon, which looks surprisingly docile. The dragon can symbolize evil, but here Mary is likely represented as “the second Eve,” an Eve who would have resisted the serpent’s temptations in the Garden of Eden.

How the sculpture came to the collections

In the early 19th century, Edshult Church was a small red-painted timber church with red shingles. By the late 1830s, it was to be replaced with a new stone church. The wooden church was demolished in 1838, and both materials and furnishings were sold at auction, spreading pulpits, altar rails, paintings, and sculptures into the local community.

Traces and reuse

Nils Månsson Mandelgren, a 19th-century Swedish folklorist, artist, and art historian, documented and collected medieval Swedish cultural heritage for the Academy of Letters. He managed to trace some of the church’s objects. Villagers had used planks from the painted interiors for stables and the poorhouse’s wood shed. The pulpit was repurposed as a chicken coop or doghouse at Skäljarp farm.

He drew some of the painted planks and published them in Monuments scandinaves du moyen age. Even though the church no longer exists, Mandelgren’s sketches provide insight into the paintings.

The bicycle search

Andreas Lindblom, a Swedish art historian and museum curator at the Swedish History Museum (then called the State Historical Museum) in the 1910s, followed Mandelgren’s traces. In the summer of 1912, he searched for preserved objects from Edshult Church.

He located fourteen painted planks in the poorhouse wood shed. Lindblom knew that the Madonna image from the church auction had been sold to a farmer, who then passed it to another farmer named Birger.

By asking around from farm to farm, Lindblom finally learned who possessed the Madonna nearly a century later: a farmer in the village of Ärnaberg. He wrote: “Fredrik Samuelsson (the farm owner) instructed his daughter to retrieve the image. The farm girl resolutely took the Mother of God in her arms and carried her down the stairs.”

Mary in Miniature

Images of Mary and prayers to Mary have been preserved from many different contexts, some surprising to us. Marian images and texts appeared on jewelry, daggers, drinking vessels, fittings, spoons, matchlocks, and tiled stoves. Religious motifs often appeared on objects that were close to people and touched or looked at frequently.

On a 15th-century finger ring found in Borgholm on Öland, Mary is depicted in half-length, surrounded by a fence of twigs. The twig fence is a metaphor for paradise—the Garden of Eden as a better world separated by high walls.

Ring with miniature Madonna

Found in Borgholm, Öland.

Apocalyptic Madonna

Another motif in small art is Mary as the Apocalyptic Madonna, surrounded by a halo and standing on a moon. On this ring, Mary is depicted in half-length within such a halo, surrounded by seven semi-precious stones of different colors, likely symbolizing Mary’s Seven Sorrows. The ring is said to have been the engagement ring of the parents of Gustav Vasa, king of Sweden.

Ring with Apocalyptic Madonna

Likely Cecilia Månsdotter’s wedding ring.

Mary in Bergslagen

People in the Middle Ages did not only practice religion in churches. There were also associations called guilds, which played an important role in religious life. The guilds held memorial feasts for deceased members, donated money to church altars, and funded memorial masses. Some guilds were specific to certain trades, while others were open to people from all social classes, both men and women.

Objects with Marian prayers or images were used by people from many social classes, in many forms, and could be worn by both women and men. Both men and women could also be members of Marian guilds.

Seal stamp

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Medeltida liv

The guilds often had a patron saint, which could appear on their seal. The seal functioned in the Middle Ages roughly like a signature today. Seals confirmed a document’s authenticity and content and were often of high artistic quality.

An example is the seal stamp from the Norberg bergslag, showing Mary with the Christ Child. In her left hand, she holds a lily staff. Around the edge of the seal is the inscription stating it belongs to the Brotherhood of Saint Mary at Järnberget.

Protector of humanity

Why was it so important to surround oneself with images of Mary and Marian prayers? Today we think of our senses as biological processes that take in information and pass it to the brain. In the Middle Ages, people believed that sight and touch functioned as a kind of communication channel between the senses and the soul. This affected how images and texts were used; they served as aids in devotional practices such as meditation and prayer.

The cult of saintly relics was also based on the idea of being close to the sacred—seeing it, touching it. This was thought to influence the soul and its fate after death. In church, it was important to see the Eucharist, believed to be transformed into Christ’s body through the miracle of the mass. Similarly, surrounding oneself with holy images and prayers had special significance for medieval people.

Mary in Monasteries

Archaeologists have also found objects related to the Virgin Mary in medieval monastery excavations.

A monastery is a building designed to house a religious community of men or women living according to a specific rule. During the Middle Ages, as today, there were many different monastic orders—Benedictines, Cistercians, Dominicans, and Franciscans being among the best known in Sweden.

Mary and Alvastra monastery

The first Cistercian monasteries in Europe were founded in late 11th and early 12th-century France. They arrived in Sweden in 1143 or 1144. Sweden had both male (monks) and female (nuns) Cistercian monasteries, most founded in the 12th and early 13th centuries.

The first monasteries were founded in Alvastra in Östergötland and Nydala in Småland. King Sverker the Elder and Queen Ulvhilde likely founded Alvastra, while Nydala may have been founded by Bishop Gisle. Life in the Cistercian monasteries revolved around prayer and mass. They farmed, practiced medicine, embroidered, wove, read, and wrote—a rare skill in medieval Sweden.

Abbot's crook

All Cistercian monasteries were named after Mary. Objects related to the Virgin Mary have been found in several Swedish Cistercian monasteries. In Alvastra, a male monastery, archaeological excavations uncovered a small ivory Madonna. It was mounted on a crook, a staff with a hook at one end, carried by the abbot as a symbol of authority. Mary is depicted seated on a throne wearing a crown, likely part of a motif called the Coronation of the Virgin, where Mary is crowned Queen of Heaven by Christ. The crook was made in Paris in the 14th century and imported to Alvastra.

Gudhem nunnery and Marian objects

Gudhem nunnery in Västergötland was founded shortly before 1175, first mentioned in written sources then. It was a nunnery, and in 1250 received a large donation from Queen Katarina Sunesdotter, who was also buried there. Her tombstone is exhibited at the Swedish History Museum.

A small bronze fitting from Gudhem nunnery depicts an “M” with a crown—a symbol of Mary. It was found in the monastery courtyard.

"M" for Mary

A small bronze fitting found at Gudhem nunnery.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Medeltida liv

The second fitting likely adorned one end of a belt. It features letters used in the Middle Ages, an A and an M, standing for Ave Maria, the opening words of the prayer of the same name. Below the letters is a small dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit. The fitting may have been worn on a nun’s belt as a daily reminder of her primary duty: prayer. In monasteries, the design of everyday objects was influenced by religious symbolism. Fittings with Marian motifs were common in nunneries. Mary likely held special significance for medieval women.