The ritual meal

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Today, we might not think of this connection as self-evident. But the Christian Eucharist is a clear example of a shared ritual meal: the breaking and eating of bread, and the drinking of wine. Long before Christianity arrived, however, there were links between food and religion in Scandinavia, although with different ingredients. Some votive finds from the Early Iron Age (500 BC–AD 550) contain remains that can only be interpreted as sacrificial meals. This is the case, for example, at Skedemosse, in the heart of Öland.

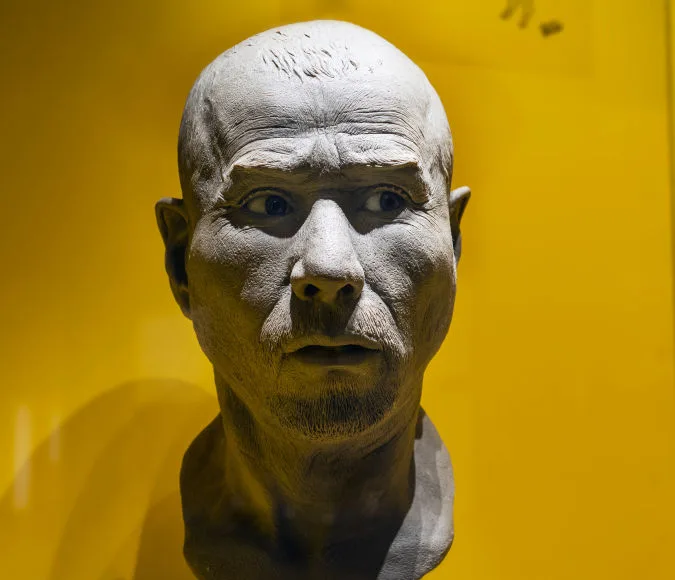

Part of a horse's jaw

Horsemeat in sacrificial feasts

These finds generally consist of the bones of animals that were both sacrificed and eaten. Almost without exception, the bones are from horses, and most are split, indicating that people sought to extract the nutrient-rich marrow.

Horse bones are found not only in large sacrificial deposits, but also at certain settlement sites. During an excavation in 1986 in Tibble, Litslena parish in Uppland, archaeologists uncovered a pit containing the remains of sacrificed and consumed horses.

No horse bones were found in the waste pits used for everyday food preparation, where bones from cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were common. This special pit strongly suggests that horsemeat held a specific ritual significance and was consumed only in particular ceremonial contexts.

Horse bone

Sagas and chronicles speak

Icelandic sagas written down in the early Middle Ages but recounting much older events contain numerous references to horsemeat being eaten in cultic settings. One tale tells of King Olaf Haraldsson (better known as Saint Olaf) refusing to participate in a sacrificial feast because it involved eating horsemeat. To avoid deeply offending the worshippers, however, he leaned over the pot and inhaled the steam from the cooking meat. This, it was said, was sufficient.

Adam of Bremen, writing in the mid-11th century in his chronicle of the Archbishopric of Hamburg-Bremen, also described horse sacrifices as part of religious rites.

Even the Roman historian Tacitus, writing as early as the first century AD, reported that among the peoples north of the Roman frontier, horses were used to deliver oracular messages.

An animal of the elite

Why the horse came to be associated with sacrificial rites remains unclear. It clearly held special symbolic significance from an early stage. Horses appear in Bronze Age rock carvings and, in that era, were depicted pulling the sun across the sky.

In one way or another, horses came to be viewed as extraordinary animals. Their meat was reserved for religious rituals and the communal meals that were a central part of these ceremonies.

It was likely not within everyone’s means to sacrifice a horse. When evidence of ritual meals involving horse bones is found at a settlement, it may indicate the presence of a local elite. Such leaders may even have used these communal meals to reinforce their own authority.

The act of distributing food has always been powerful. It creates bonds of obligation and gratitude. Just as the Roman emperors distributed bread and staged games to secure popular favour, so too might Nordic chieftains have served horsemeat in abundance. The goal, and the outcome, was likely the same: to secure power and prestige.