The palace chapel that became a kitchen

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

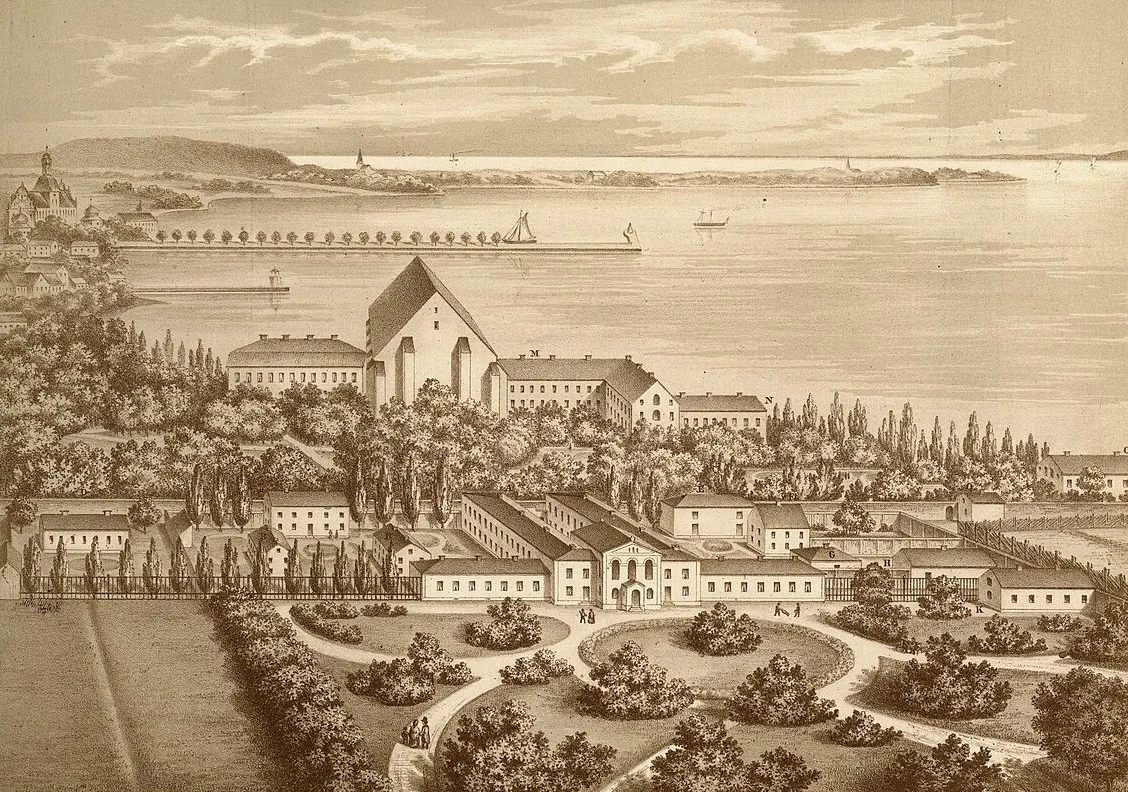

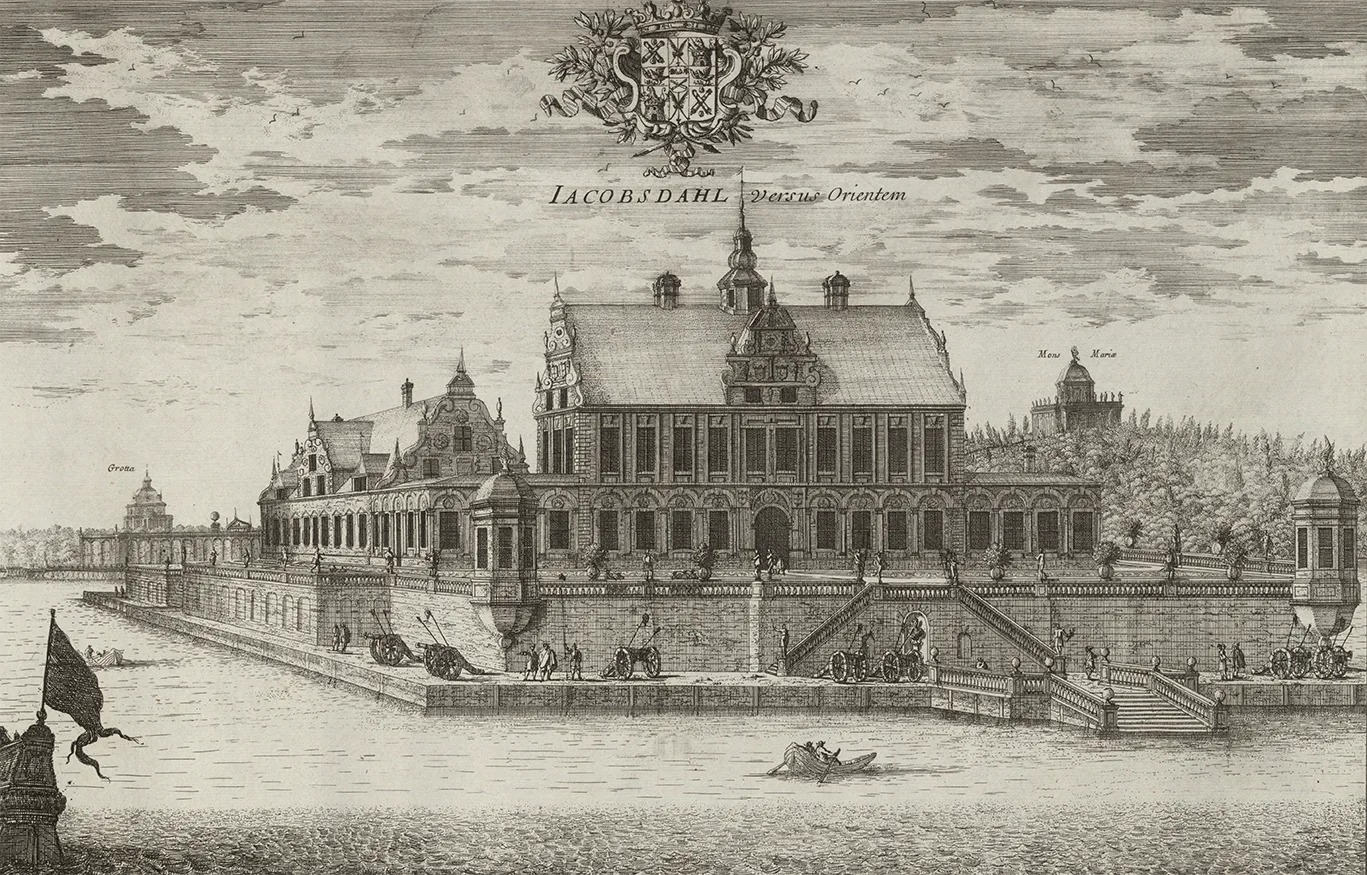

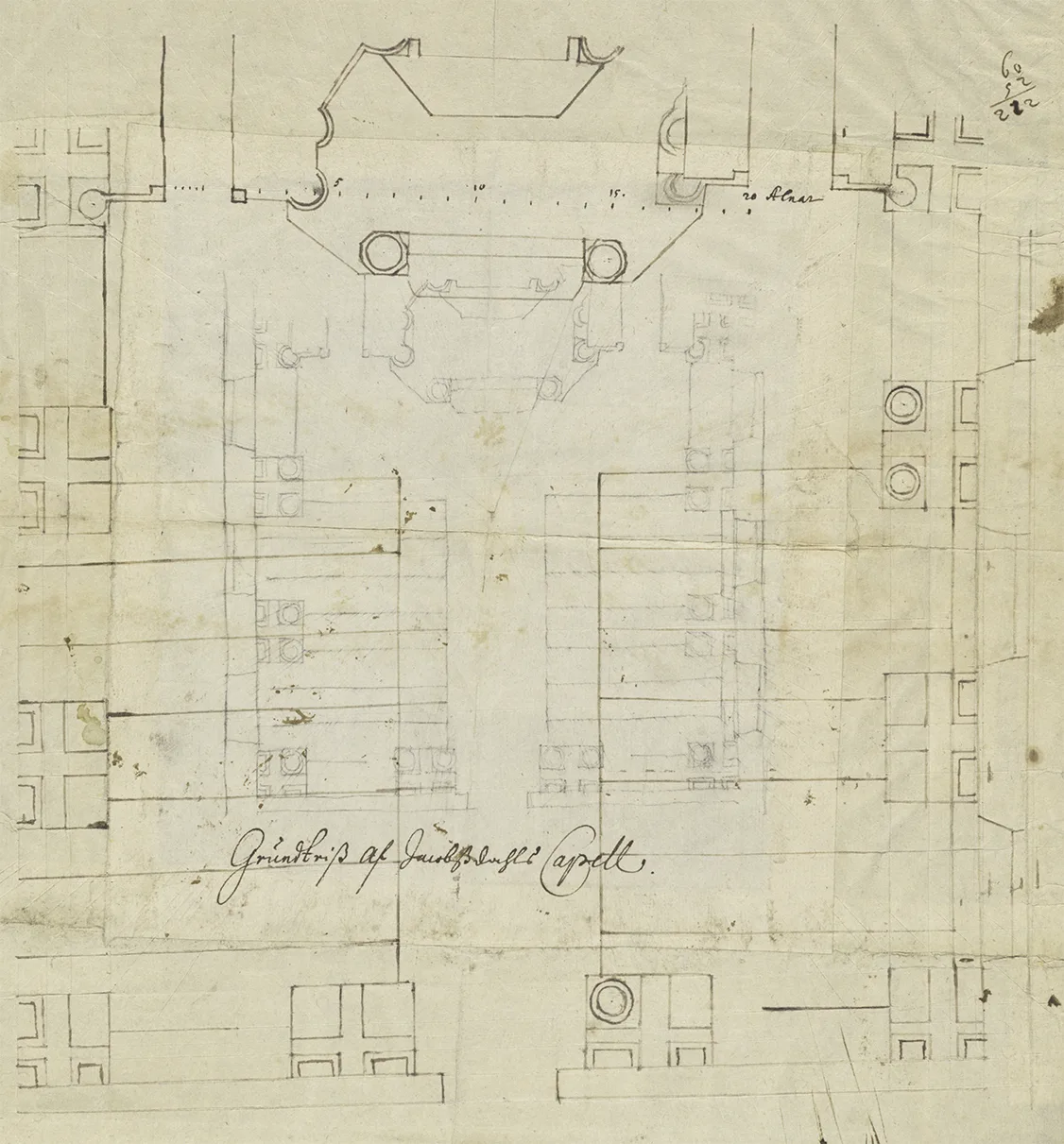

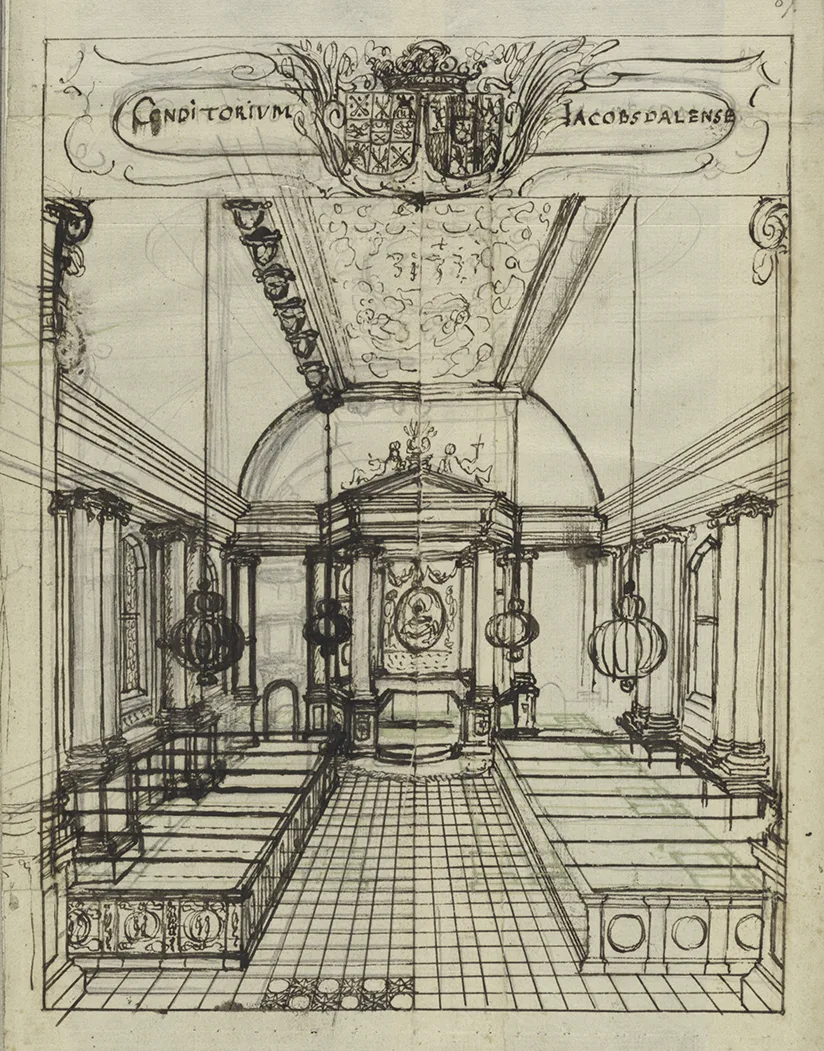

What many wedding guests or weekend strollers may not realise is that it had a predecessor, an earlier, grand palace chapel located inside the palace itself. That once magnificent chapel has, in fact, been converted into a kitchen. Ulriksdal was originally called Jacobsdal and was built in the 17th century by the de la Gardie family. Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie was one of Sweden’s most powerful men and largest landowners, with more than 1,000 estates and manors to his name. The architect of the chapel was Jean de la Vallée, best known for designing the House of Nobility (Riddarhuset) in Stockholm.

The chapel’s interior was lavishly decorated, as shown in Erik Dahlbergh’s illustrations for the Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna series, though he occasionally exaggerated to present the Swedish empire in the most impressive light possible.

A household fit for a king

In 1774, King Gustav III ordered the chapel to be demolished to make way for 12 new rooms, primarily intended for the palace staff. In the 1920s, part of this space was converted into a palace kitchen for Gustav VI Adolf. It became Sweden’s most modern kitchen, equipped with an electric stove, a food lift, and an internal telephone. The kitchen staff could call the butler’s pantry one floor up to announce that the food was ready and loaded into the lift, the serving staff then simply had to wind the food up to the dining rooms upstairs.

The chapel interior was dismantled, but much of its furnishing was preserved and repurposed. The floor, for example, was reused in Gustav III’s Museum of Antiquities at the Royal Palace in Stockholm, where it remains to this day. Some objects from the chapel interior are kept in the collections of the Swedish History Museum.

Splendid pieces preserved

The angels from the chapel’s altarpiece were carved in 1662 by Henrik Lichtenberg, while the oil painting by Hans Georg Flacht was completed four years later. At the bottom of the canvas is inscribed Ecce Homo ("Behold the Man"), the words spoken by Pontius Pilate when he presented the beaten Jesus to the crowd, wearing a crown of thorns and a purple robe.

Ecce homo

Painting on display in the Baroque Hall.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Barockhallen

Five smaller oil paintings from the chapel have also survived. Originally mounted on the pulpit, they depict Jesus and the four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. They were very likely painted by the French artist Nicolas Vallari, who was active at the palace at the time. The reclining lamb, finely carved in wood with curly gilded fleece, perhaps also adorned the pulpit.

Agnus Dei

Gilded wooden sculpture depicting the Lamb of God.

A few other items from the chapel also survive. Two inscription plaques with Latin texts were carved by the same artist who created the angels. One reads: OMNIS SPIRITUS LAUDET (“Let everything that has breath praise the Lord,” Psalm 150). The other: VERBUM TUUM VERITAS EST (“Your word is truth,” John 17).

Another object from the chapel is a gueridon, or a candle stand, shaped like a carved wooden urn with a sacrificial flame. The sacrificial fire appears in the Old Testament, where people sought reconciliation with God through burnt offerings, such as lambs. In church furnishings, the motif symbolises the faithful Christian’s communion with God, and also Christ’s sacrifice for humankind.

Gueridon

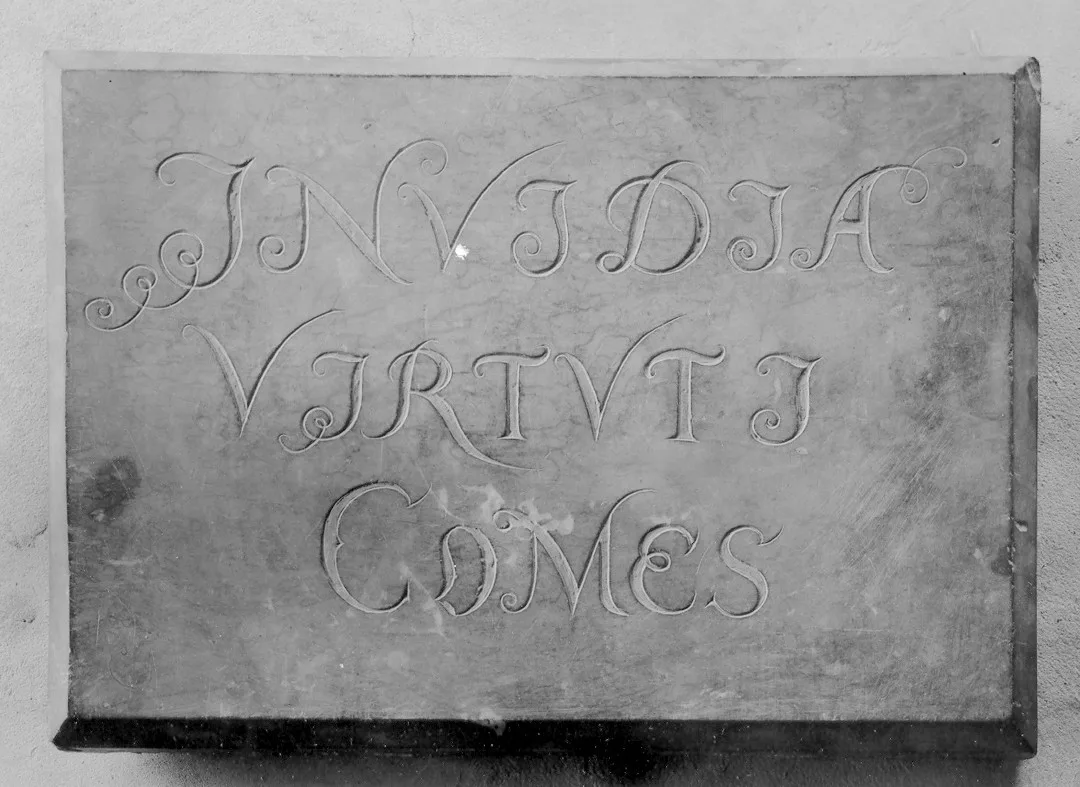

A plaque made of black limestone bears the Latin phrase INVIDIA VIRTVTI COMES (“Envy is virtue’s companion”). It’s possible that this slightly boastful message was intended to honour the chapel’s patron, Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie. After the de la Gardie family, Ulriksdal Palace became royal property. From that period comes a marble cartouche bearing the monogram of Dowager Queen Hedvig Eleonora, which once hung in the chapel.

Although only fragments of the once-splendid chapel survive today, the preserved furnishings and illustrations still allow us to form a fairly vivid impression of how it once looked, before it became Sweden’s most modern kitchen.