The old man and the child – a grave from Skateholm

Stone Age

12,000 BC – 1700 BC

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

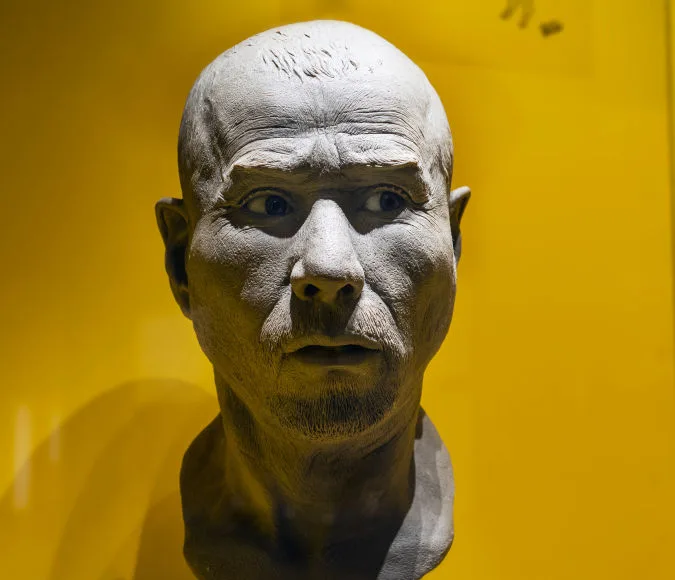

In this grave lies a man approximately 60 years old. Closely beside him, with its face turned toward his chest, is a small child aged 4–5. Both the man and the child were placed on their sides, facing each other. One of the man's arms appears to be encircling and protecting the child's head. Ornaments made from bear teeth, large pieces of amber, and a bone point lay on the child's chest.

The child’s body had been sprinkled with red ochre. Red ochre is a pigment that was common during the Stone Age and is often found in graves. It originates from iron-rich deposits in water from streams and springs, which, when collected, dried, and heated, turn a strong red color. The traces of red ochre in graves may come from dyed clothing or may have been applied directly to the body. The reasons for its use are unclear, but it is believed to have had strong ritual significance.

The discovery of the grave

Skateholm is known as a site with numerous Stone Age graves. It was first identified in the 1930s when workers digging for gravel discovered several skeletons. Only one of the skeletons was examined and preserved in the early 20th century. It wasn’t until the 1980s that archaeological excavations were carried out.

The Skateholm grave displayed at the Swedish History Museum is one of several excavated in blocks of earth. Archaeologists first exposed the grave in the field after unearthing the skeletons and surface finds. The skeletons and the surrounding soil were then stabilized using many liters of clear lacquer.

Once the lacquer had dried, the archaeologists built a steel box around the entire grave. The box weighs nearly 800 kilograms and eventually made its way to the Swedish History Museum. It is now on display in one of the central areas of the exhibition Prehistories. The individuals in the grave still lie in the soil in which they were originally buried. The grave is known as "the old man and the child."

Grave goods and rituals

During excavation, archaeologists initially interpreted that the child had been buried later than the man. This was partly due to the unusual angle of the man’s right hand. Later studies, however, suggest that both were buried together at the same time. In a contemporary perspective, their remains convey a universal human expressions of love, grief, and care. However, not all graves at the site evoke such feelings. The graves at Skateholm are known to contain traces of many different types of rituals, and there are also signs of violence, both before and after death.

One person, who had a healed but serious injury to the thigh bone, appears to have been killed by an arrow found embedded in the pelvis. This individual also seems to have been dismembered before burial. Another person was buried lying on their stomach. In the fill of the grave, a few centimetres above the body, several arrowheads were found in positions suggesting they were shot into the grave at the time of burial.

In another grave, selected bones from the deceased were removed after the body had decomposed. There are also pits containing objects but no skeletons. Perhaps the dead were fully removed, or maybe these were cenotaphs (symbolic graves). Traces of fire have also been found in some graves, and burnt human bones have been discovered at the site in what some interpret as burial contexts.

Dog burials

The site is also known for its dog burials. Some dogs were killed and placed in the fill of a few graves; others were laid down whole or in parts as grave goods alongside humans. There are also separate dog graves, where in some cases the dogs received grave goods and were sprinkled with red ochre, just like the humans. A beautifully decorated antler hammer was found with one of the dogs.

There are differing opinions on how to interpret these various traces of rituals. Were they unusual practices at the time, or did they reflect norms and beliefs about death and the afterlife?

One idea archaeologists propose is that Skateholm was a place for disposing of the bodies of people who were in some way deviant or dangerous, and that the use of islands was a way to separate the dead from the living.

Others argue that such a separation didn’t exist, that the boundary between the living and the dead was not clearly defined. In this interpretation, Skateholm is instead seen as a settlement area where people lived ordinary lives and simply buried their dead in and around the place where they lived.

Tooth pendant

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider

What does Skateholm tell us about Stone Age people?

At Skateholm, not only graves have been found, but also cultural layers containing finds such as tools, food waste, and animal bones. Other remains include hearths, pits, postholes, and various structures, among them a small number of houses. Some of these houses have been interpreted as dwellings, but one house containing red ochre has been linked to the burials.

It may have been a tent for the dying or for the dead awaiting burial. It’s difficult to determine whether the food remains, fire traces, and structures were part of the many rituals surrounding the dead or related to everyday activities. How these features are interpreted greatly influences how the site as a whole is understood.

The various areas around the lagoon that were used during the Mesolithic appear to have been in use for a long time. Dating and finds suggest that they were used for nearly 2,000 years, from around 6000 to 4000 BC. This period marks the end of the Early Stone Age and is associated in Skåne with the final phase of the archaeological Kongemose culture and the subsequent Ertebølle culture.

Throughout this period, people lived as hunters, fishers, and gatherers. However, at this time, there were already nearby cultures practicing agriculture and animal husbandry. The people of Skateholm must have been aware of this, but they do not seem to have had the means, nor the desire, to become farmers.

They did, however, adopt something else new during the last centuries of the Mesolithic: the craft of pottery. The knowledge of pottery is believed to have come from the south, where pottery traditions in the Ertebølle culture of northern Poland and northern Germany are somewhat older than those in Denmark and Skåne. Ertebølle pottery in Skåne has its own distinct style and characteristics, and it represents the oldest pottery found within present-day Sweden.