The grave of Ulf Gudmarsson

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

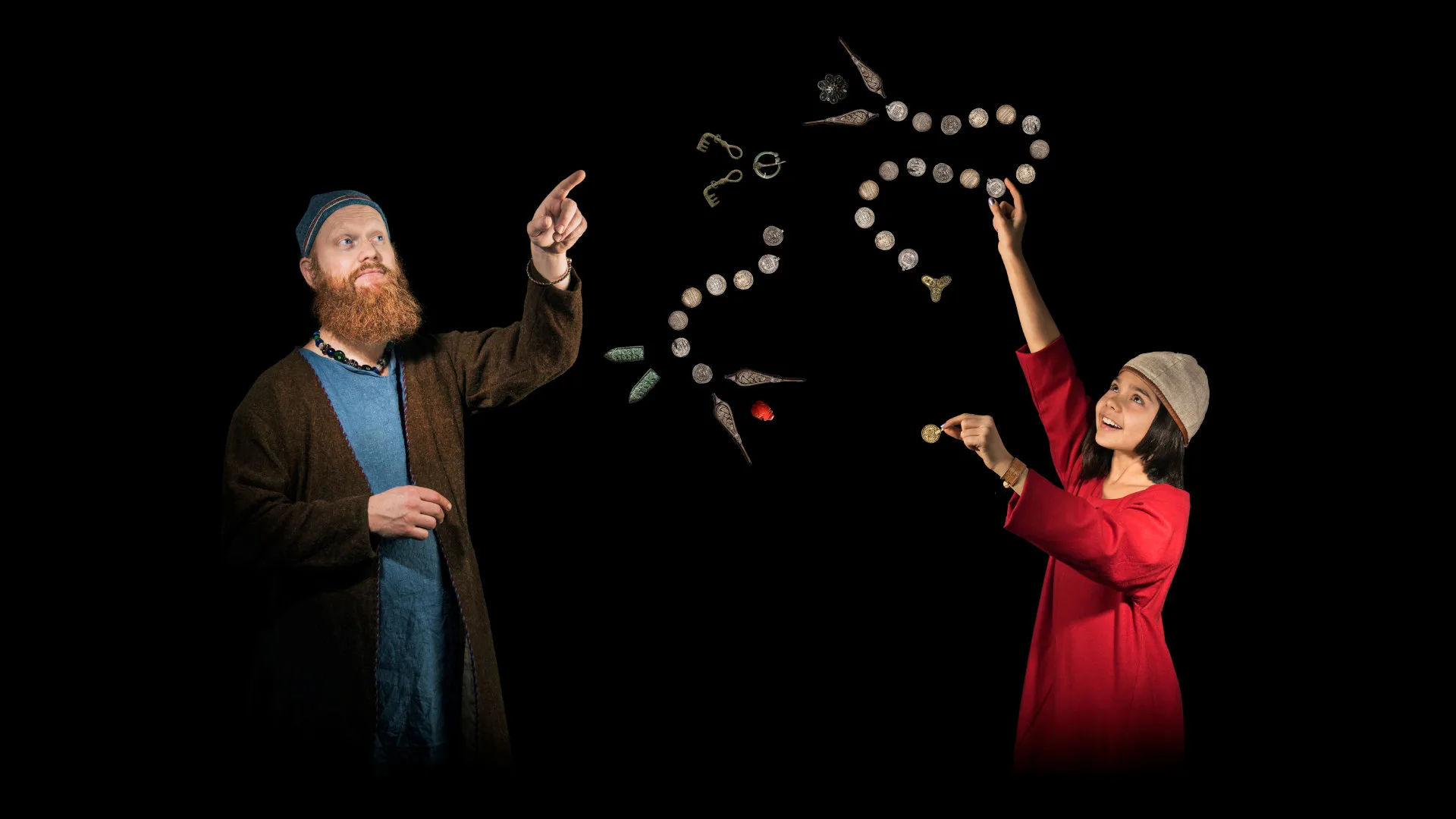

Ulf Gudmarsson was a medieval lagman (lawman). At the age of eighteen he married Birgitta Birgersdotter, later known as Saint Bridget. Together they had eight children and even undertook a number of pilgrimages.

On their way home from Santiago de Compostela, Ulf fell ill. He moved in with the Cistercian monks at Alvastra, where he spent his final years. It was also there that he died and was buried. His grave was marked with a slab inscribed:

Here lies the noble knight Sir Ulf Gudmarsson, lawman of Närke, once the husband of the blessed Birgitta, who died in the year of Our Lord 1344 on the 12th of February.

A simple, austere grave

The gravestone is plain: apart from the inscription, it bears no decoration. This simplicity was entirely in keeping with the austerity the Cistercians advocated in their churches, an approach Bridget herself followed in the convent she founded.

The gravestone cannot have been carved immediately after Ulf’s death, since the inscription refers to Birgitta as deceased but not yet canonised. It may therefore have been made a few years after her relics were returned to Sweden in 1374.

Ulf Gudmarsson's grave

From Alvastra Abbey, Östergötland.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Sveriges historia

A complete replica

In the spring of 2023, a replica of the stone was produced using the very same limestone as the original, quarried at Borghamn by Mount Omberg. The inscription was carefully reproduced. While the original survives in two pieces and lacks a corner, the replica is complete and now lies on the grave site at Alvastra Abbey.

The skeletons in the grave

In the summer of 1930, archaeologists excavated the burial site at Alvastra Abbey, uncovering the remains of three individuals. The skeletal fragments, badly damaged and lying together in disorder, had most likely originally been placed in a wooden coffin. They were transferred to the Swedish History Museum, and in 1952 osteologist Nils-Gustav Gejvall carried out an analysis.

According to his study, the grave contained a man, a woman, and a child. The man assumed to be Ulf Gudmarsson was around 50 years old, 180 centimetres tall, and strongly built. Gejvall described his skull as:

Fairly robust with rather pronounced brow ridges and clear evidence of a strongly developed nasal root. The back of the head protrudes markedly. The lower jaw is robust with steeply rising rami and furnished with two strong mental tubercles. Of the nine teeth that remain, they are small, with signs of periodontal disease and irregular wear.

The woman was estimated to have been 25–30 years old and 163 centimetres tall. Her skull was described as

more delicate than the man’s, though with a similarly prominent back of the head. The attached upper and lower jaws show strong but only slightly worn teeth. All wisdom teeth had just erupted but show very little wear.

The child was between 8 and 9 years old. Its stature could not be determined. It has been suggested that two of Ulf and Bridget’s children were laid to rest alongside their father.

Modern DNA and recent analysis

In 2004, DNA tests were carried out on the skeletons in the hope of establishing kinship between the three individuals, but the results proved inconclusive.

When an osteologist re-examined the remains in 2024, she noted that the man’s skeleton was unusually large and robust. In comparison with the woman, the difference in size was striking. His femur measured over half a metre, giving an estimated height of around 187 centimetres. The average height for medieval men was considerably shorter, around 173 centimetres.

The discrepancy between the earlier estimate of 180 centimetres and the later 187 is due to a new method of calculating stature from skeletal measurements. Both figures were based on the same bone, but using different formulae.

Although Ulf was ill for several years before his death, most diseases do not leave visible traces on bone. The male skeleton shows no signs of pathological change, not even worn joints, which were common among middle-aged men of the time. Overall, the evidence suggests a man who had lived a privileged life, with good access to food and without excessive physical labour. Perhaps this was indeed Ulf Gudmarsson, or perhaps another member of society’s elite.