The Gerum cloak – Sweden’s oldest preserved garment

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

The cloak takes its name from the location where it was found: the parish of Östra Gerum in the province of Västergötland. Oval in shape, it measures around 2.5 by 2 metres. It is made of woven wool and has taken on a brown hue from the bog water in which it was discovered. The cloak has been dated to between 360 and 100 BC, placing it in the Pre-Roman Iron Age.

The Gerum cloak

A peculiar find

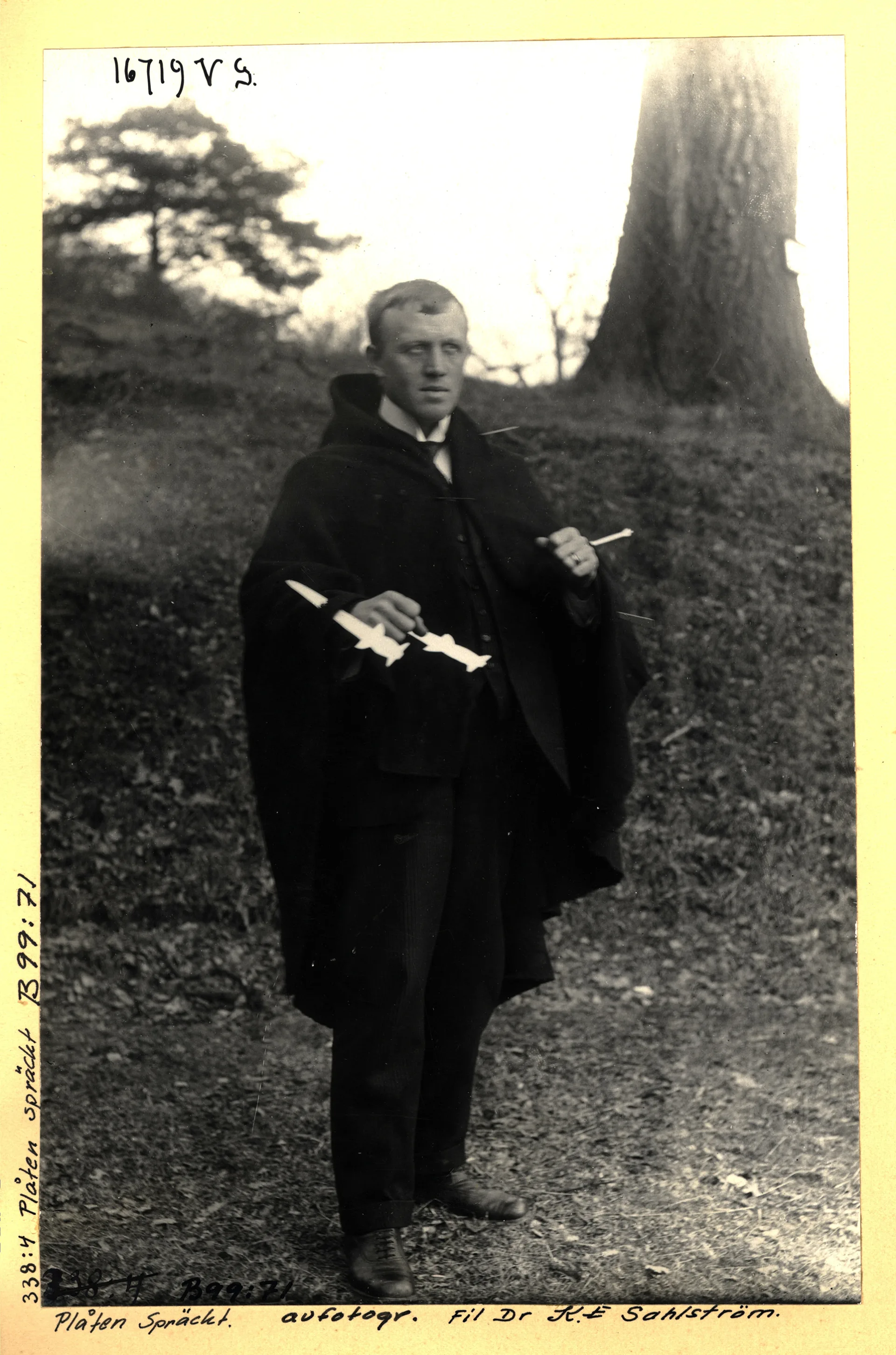

Shortly after their morning coffee break in 1920, a worker named Fredrik Klasson struck a large piece of oak while he and two others were cutting peat on Gerumsberget. Beneath the oak lay two upright stones resting atop a larger, flat one.

As they continued digging, they encountered “something tough”: the folded-up cloak. It had been buried 1.45 metres below the surface. The men initially believed they had uncovered Queen Margaret’s cloak, as local legends claimed the medieval queen had once visited the area.

One of the men, Erik Rydberg from the nearby Åsatorpet croft, later recalled:

When we pulled the cloak out, I laid it on the edge of the hole and left it there until evening, when I carried it home. The others thought it wasn’t worth the bother—it was just an old rag, only fit for a rag-and-bone man. And there were holes in it, so I couldn’t very well sew any trousers from it, they said. They laughed and mocked me as I carried it home. But I thought it was something remarkable and brought it home anyway, even though it soaked me through, being so wet and heavy. When I got home, I hung it up in a shed to dry, and there it stayed for several weeks. While it hung there, several people came by to have a look at it.

The mockery ceased when the men received 500 kronor from the National Heritage Board in exchange for the cloak.

Found in a bog, on a moutain

Gerumsberget is a table mountain that stands out starkly in the landscape with its steep sides and broad, flat summit. The cloak was found near the edge of the bog, close to one of the mountain's precipices. A subsequent geological investigation revealed that the cloak had been placed in a pit likely dug for the purpose. At the time, the surface would have been relatively dry, though the pit soon filled with water. The surrounding area consisted of damp, marshy deciduous woodland. Over time, layers of peat formed over the site.

The cloak had been folded into a bundle and placed in the pit, with three stones, each several decimetres in size, laid on top, possibly to hold it in place or to conceal it. Was the stabbing a crime that needed covering up? Or might there have been other reasons for placing the cloak there?

Mountains were often regarded as sacred places during the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Some summits are encircled by Bronze Age enclosures, while others feature cairns from the same period. A prominent mountain such as Gerumsberget likely held special significance for a long time.

It was also not uncommon for objects to be offered to bogs and wetlands, both during the Pre-Roman Iron Age and in centuries before and after. In fact, several individuals appear to have been ritually executed and deposited in such wetlands. Bog offerings were already an established tradition by the time the Gerum cloak was placed in the earth, although finds from wetlands atop mountains are rare.

More questions than answers

The Gerum cloak has sparked academic debate and interpretation. Scholars have questioned its dating, speculated about the puncture marks found in the fabric, and puzzled over how it ended up in that particular bog in Östra Gerum.

Where did the holes come from? And were those bloodstains around them? The cloak was examined by the National Forensic Centre (SKL), which concluded in its final report that the damage was most likely caused by five stab wounds inflicted by a knife or dagger. The blows appear to have struck the chest, abdomen, back, and neck. According to SKL, such injuries would be considered life-threatening and could easily prove fatal.

There is no body, no blood—so we are left no closer to solving the mystery.

Colour analysis

The cloak was woven in what is known as a houndstooth pattern, which requires at least two colours. Although it now appears as two shades of brown, it may originally have been made using different colours.

Its current brown tones are the result of having lain in a peat bog for many centuries. Organic matter from the bog seeped into the water and stained the cloak. As early as the 1920s, chemical analyses were carried out. Professor Gustaf Sellergren and Dr. Carl Setterberg concluded that the yarns had not been dyed. Instead, they believed the cloak was made from naturally coloured brown and white wool.

At the time, research lacked today’s technical capabilities. Yet modern analysis confirms their conclusions: the cloak was indeed woven from undyed brown and white wool.

Wool analysis

An important aspect of the research surrounding the Gerum cloak concerns the material from which it was made. Earlier studies concluded that the cloak was partly woven from the hair of wild animals, but more recent findings point in a different direction.

Today, we know that the wool used in the Gerum cloak is entirely from sheep. This has been confirmed by new analyses. We also know that the wool was naturally coloured, white and brown. However, the earliest tests carried out in the 1920s indicated the presence of deer, roe deer, and cattle hair. So how can this discrepancy be explained?

The wool contains so-called guard hairs. These are dead hairs with a medullary canal, making them relatively coarse and stiff, quite unlike fine sheep’s wool. For this reason, earlier researchers assumed the cloak contained hair from wild animals or cattle, whose coats typically feature a high proportion of such guard hairs. Modern analyses, however, have shown that the guard hairs actually originate from sheep. This means the entire cloak was woven using only sheep’s wool.

The wool in the cloak varies in quality. The wool used for the white yarn is finer than that used for the brown. The type of sheep that provided the wool for the Gerum cloak had fleece composed of both underwool and outer hairs. The underwool, which is white and short, is soft and fine. The outer hairs are longer and coarser, and serve to protect the animal from harsh weather.

Wool of this kind is known among textile specialists as Mouflon-type wool. The breeds of sheep that most closely resemble those of prehistoric times are Mouflon and Soay. The Mouflon is a wild breed that dates back to the Stone Age, and can still be found today on Corsica and Sardinia. Soay sheep, which are believed to have Bronze Age origins, still live on the Saint Kilda islands off the coast of Scotland. Both breeds typically have fleece composed of white underwool and brown outer hairs, just like the sheep believed to have supplied the wool for the Gerum cloak.