Sweden’s oldest burial monuments – red ochre graves

Stone Age

12,000 BC – 1700 BC

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Who were they? What did these graves mean to those they left behind? Archaeological discoveries reveal a fascinating story of Stone Age rituals, life, and death.

The introduction of agriculture is closely linked to the practice of building monuments for the dead. Early evidence of farming in Sweden appears around 4000 BC, first in Skåne in southernmost Sweden and then gradually reaching areas as far north as Dalarna. Around 500 years later, the first megalithic tombs were constructed, large stone chamber graves where multiple individuals were buried. Both early farming and these megalithic tombs are associated with what archaeologists call the Funnel Beaker Culture.

However, megalithic tombs are not the oldest above-ground, stone-marked graves known in Sweden. Much earlier, around 7,000 years ago, stone constructions were built over the dead by hunter-fisher-gatherers in what is now Norrbotten.

These northern graves are referred to as red ochre graves, as they are characterized by being filled with sand colored by red ochre. Red ochre is a natural pigment that was commonly used in the Stone Age and frequently found in graves from both the early and late Stone Age across Sweden.

The reason for using red ochre is still uncertain, but researchers have suggested it may have been considered to possess healing or purifying powers, or perhaps associated with the color of blood and life, thus perceived as life-giving.

The red ochre graves in Norrbotten are also the oldest known graves in Sweden with an above-ground stone structure. These structures typically consist of stone packings, which, while subtle, remain visible on the surface to this day.

Stone settings with red ochre

About 20 red ochre-filled stone settings have been documented. These graves are mostly round, measuring between 3 to 6 meters in diameter. A few are oval or rectangular in shape. All of them are located in Norrbotten, near the rivers Piteälven, Luleälven, and Kalixälven. They are the only known Mesolithic graves (early Stone Age) in northern Sweden.

A likely similar grave has also been found in northern Ostrobothnia in Finland, raising the possibility that this burial tradition may have been practiced along the entire Bothnian Bay coast during the Late Mesolithic.

These graves were built to be visible and became landmarks in the landscape, places that Stone Age people could relate to and revisit.

They are often not isolated: archaeological finds such as knapped stone, fire-cracked rock, and pits have been discovered nearby. These are interpreted as traces of dwelling sites, suggesting a close connection between graves and settlements. In some cases, house foundations (dwelling mounds) have also been found nearby.

Artefacts near the graves may also represent remnants of burial rituals or later visits to the grave. This interpretation has been applied, for instance, to the area around a grave at Lillberget outside Överkalix, dating to around 1,000 years later.

However, it can be difficult to determine archaeologically what such features, like a hearth near a grave, were actually used for, especially when they are roughly contemporaneous.

Archaeologically excavated red ochre graves

When these stone settings were first discovered, they were believed to be from the Iron Age. It wasn’t until a research project in the 1990s that archaeologists noted a pattern: all the red ochre-filled settings lie at 75 meters above sea level or higher.

In relation to post-glacial land uplift, this altitude corresponds to the end of the Mesolithic, assuming these places were once coastal. This theory was later confirmed when two of the graves were excavated under the direction of archaeologist Lars Liedgren.

One grave in Manjärv, in Älvsby parish, and one in Västra Ansvar, Överkalix, were investigated. In the 2020s, a third grave is being excavated at Ligga, Jokkmokk.

The grave at Manjärv

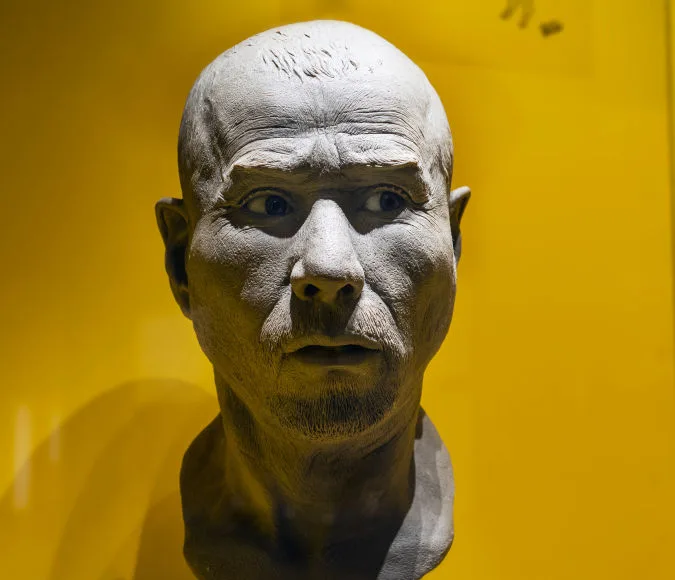

The remains from the grave excavated in 1991–1992 in Manjärv are now part of the collections of the Swedish History Museum. The excavation revealed traces of at least two individuals.

The first burial was placed in a 70 centimetre deep pit, whose bottom had been lined with fine, stone-free sand. Then a layer of red ochre-mixed sand was added, upon which the body was laid. At the time of excavation, the red ochre layer covered an area 2 meters long and 0.25–0.5 meters wide, and was 3–7 centimetres thick.

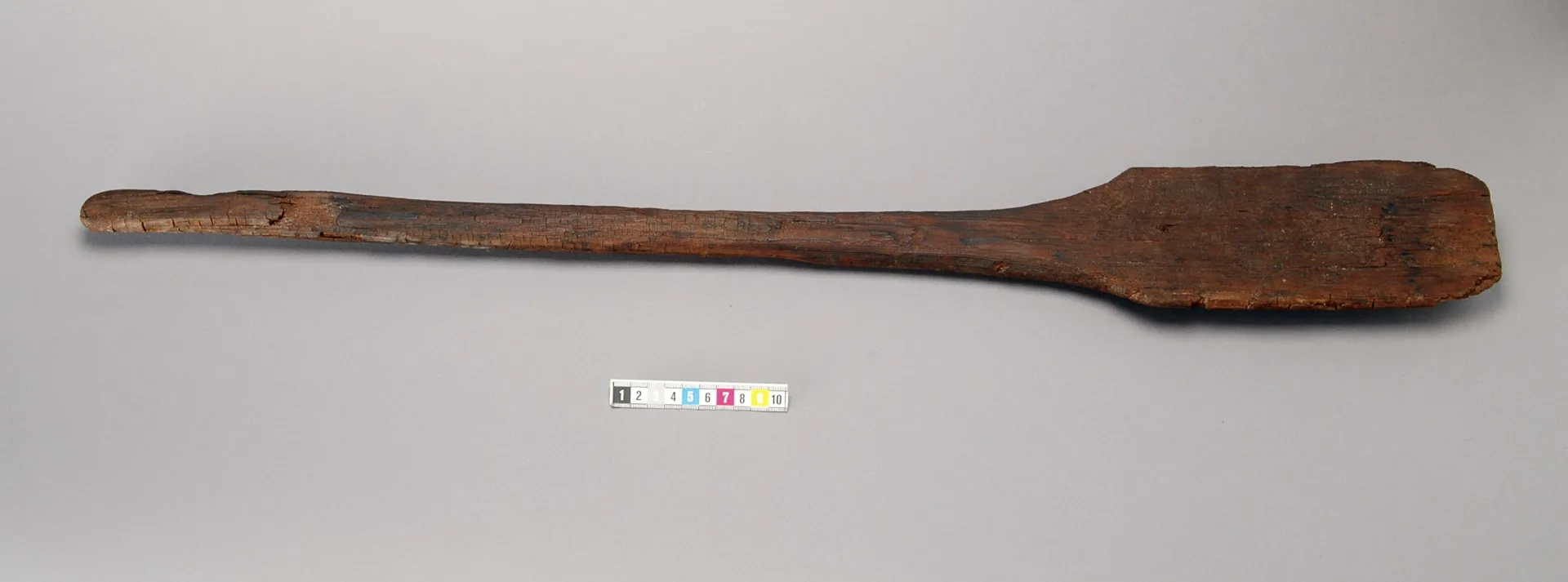

It was in this layer that the faint, heavily degraded remains of a skeleton were observed. The skeleton was entirely embedded in red ochre, and a tool made of slate found between the knees also showed strong traces of ochre. The tool may have been used as a knife.

If items made from organic material were originally buried with the individual, we cannot know, such materials would have decayed long ago in the acidic, lime-poor soil, as did any clothing or burial wrappings.

Even the skeleton was poorly preserved, visible only as faint staining and a few fragile bone fragments. Parts of the pelvis, arm bones, and skull could be distinguished, allowing the person’s height to be estimated at about 165 centimetres. The best-preserved parts were the teeth, as tooth enamel typically survives the longest. Based on tooth wear, the individual was likely 25–30 years old at the time of death.

Thanks to the remaining traces, a dating was possible: the individual died around 5200–5000 BC. At the time, the burial site was located on a small coastal island. However, the grave was not finalized immediately after the first burial; one or two more individuals were later interred.

After the first burial, the grave was covered with light gray-brown sand containing gravel and stones. On top of that, a new layer of red ochre was added, and the pit was expanded to 2.6 metres long and 0.6–1.3 metres wide.

Preservation was even poorer in this upper layer, where only a few white-colored bone fragments, confirmed as human, were observed. It is believed that one or possibly two people were buried in this layer. The worse preservation is probably due to the shallower depth of the bodies. No objects were found next to the skeletal remains.

After these final burials, the grave was filled with red ochre-colored sand and covered with a stone packing. This packing continued to be built over and around the grave, with a central fill of ochre-stained sand. In total, it became a round stone setting about 4 metres in diameter and about 0.3 metres high when rediscovered much later.

The finds from the Manjärv excavation are registered as accession number 33,746 in the collections of the Swedish History Museum.