Saint Bridget – Sweden’s most famous woman

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Birgitta Birgersdotter was born in 1303 in Finsta, Uppland. Seventy years later, she was buried in the metropolis of Rome and a few years later canonized. By then, she had mediated peace in the Hundred Years’ War, persuaded Pope Urban V to return to Rome for a period, and later predicted his death when he left the city again—events that clearly contributed to the legendary image surrounding her.

Bridget’s interactions with the great figures of her time did not end there. Even on Swedish royal soil, she made her mark as an advisor to the queen, while maintaining a position within the highest political circles throughout her life.

But perhaps it was not her worldly achievements that made the greatest impression. It was her divine revelations and visions that elevated her name within the Church and gave her the role she still holds today.

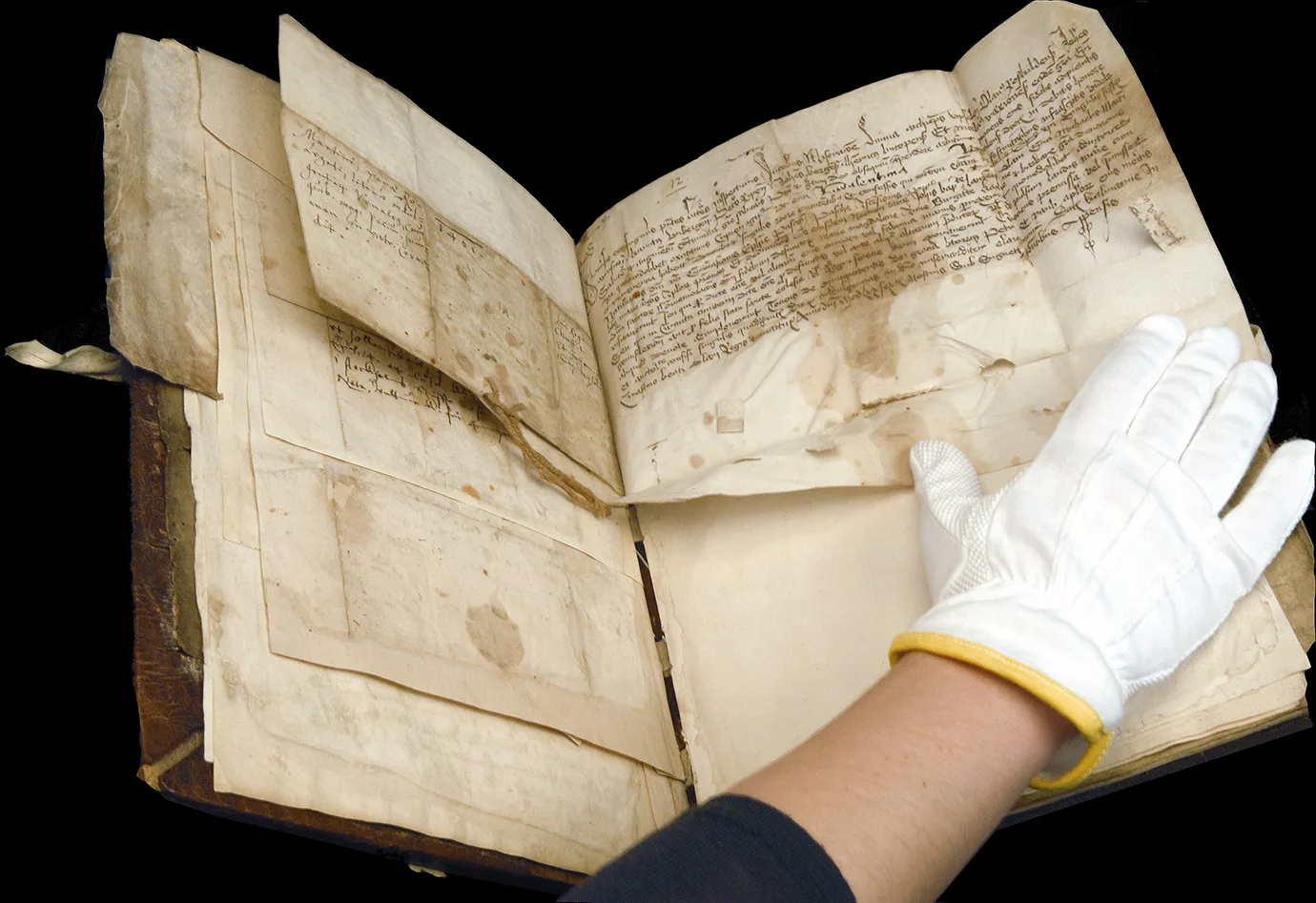

Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC BY 4.0).

Bridget’s childhood

Her father, Birger Persson, was a lawman in Uppland, a knight, a member of the king’s council, and a major landowner. He also helped write down the Uppland Law for the first time at the end of the 13th century. The Uppland Law was the regional law applied in Uppland and Gästrikland during the Middle Ages, before the mid-14th century. Birgitta’s mother, Ingeborg Bengtsdotter, belonged to the royal Folkunga dynasty.

Strong faith from the start

Even as a child, Birgitta had a strong belief in God. At the age of seven, she experienced her first vision. She saw the Virgin Mary and Jesus, who spoke to her. From then on, she began to pray frequently, feeling that God wanted to use her for something important.

When Birgitta was ten, her mother died. She then moved in with her aunt at a large estate, where she learned to read, write, and studied much about religion.

Family and daily life

At 13, Birgitta married Ulf Gudmarsson, who was 18. Marrying at that age was common at the time. At the same time, her sister Katarina married Ulf’s brother Magnus Gudmarsson. Bridget and Ulf had eight children and lived at the Ulvåsa estate, a few miles east of present-day Motala in Östergötland.

She was only 16 when her first daughter, Märta, was born. Birgitta gave birth to a total of eight children over 18 years, four girls and four boys. Four of Birgitta's children died during her lifetime, two of them as children. Birgitta and Ulf sent their children away from home relatively early for education, which was common for children from wealthy families during the Middle Ages.

Birgitta and Ulf’s Children:

- Märta (1319–1399)

- Gudmar (1322–1332)

- Karl (1327–1372)

- Ingeborg (1329–1349)

- Katarina (1331–1381)

- Birger (1333–1391)

- Bengt (1335–1346)

- Cecilia (1337–1399)

While caring for her own children and managing the estate, Bridget engaged in charitable work, founding a hospital and a shelter for women.

Birgitta and Ulf’s pilgrimages

Birgitta and Ulf were both devout and traveled to many holy sites. Once, they went to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, one of Europe’s most famous pilgrimage destinations. Birgitta is often depicted as a pilgrim, with a staff, hat, and a bag over her shoulder.

Around the age of 40, Birgitta and Ulf traveled to Nidaros (today Trondheim, Norway), another important pilgrimage site. After the trip, Ulf became ill. He refused medical treatment, believing that God determined life and death. Shortly afterward, he died at the monastery in Alvastra.

After Ulf’s death, Birgitta's life changed—she wanted to dedicate herself entirely to God. She chose to stay near Alvastra with her youngest children, distributing her properties to heirs and the poor in order to live simply near the monastery.

Wooden sculpture, Saint Bridget

From Högsrums kyrka, Borgholms kommun, Öland.

Revelations and religious calling

Birgitta received new visions in which God and saints spoke to her. She recorded everything they said—messages for kings, popes, and the entire Christian world.

God gave her a mission: to found a new monastery in Vadstena, with a stricter rule than other monasteries. She began working on it, even though many initially did not take her seriously—after all, she was both a woman and a layperson.

At Alvastra monastery, she received many visions, which she wrote down, sometimes herself and sometimes with the help of priests. There, she had the nickname “Bride of Christ and Spokeswoman.” Over 600 of her revelations have been preserved. In these, she criticized kings and churchmen, but also herself.

Pilgrimages and the struggle for her monastery

Visiting holy sites was important in the Middle Ages. Birgitta made several pilgrimages, including to Trondheim, Santiago de Compostela, and Jerusalem. In 1349, she traveled to Rome to get papal approval for a new monastic order in Vadstena—comprising both men and women, led by a woman. Despite illness, war, and the rampaging black death, she did not give up. In 1370, she received approval.

In a Rome marked by civil strife and decay, Birgitta waited nearly 20 years to speak with the pope about her order. He had fled the political unrest and was living in Avignon, France. During her time in Italy, Birgitta gained many high-ranking friends. She spent most of her time in Rome at a house by Piazza Farnese, sending letters to the pope urging him to return to Rome and approving plans for her monastery. Birgitta was likely not very popular in distant Avignon. In 1370, she finally met the pope, who approved her monastery.

While in Rome, she participated in important church festivals, prayed in many churches, and helped the poor. She continued to write down the revelations she received from God, sending messages to kings, popes, and other leaders. Sometimes they were warnings; she told them to change their ways and live as good Christians, or misfortune would follow.

Birgitta and her children before the Pope. ID 9413827. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC BY 4.0).

Death and canonization

In 1371, Birgitta embarked on a long and dangerous journey to Jerusalem with her daughter Katarina and some companions. She wanted to visit the places where Jesus had lived and died. The journey took several months and passed through dangerous regions, but Birgitta was determined. Upon arriving in Jerusalem, she received even more revelations from God, which she recorded and sent forward as before.

After the journey, Birgitta returned to Rome, now old and ill. In 1373, she died in Rome after a long life of faith, travel, and work for the Church. She never saw the new Vadstena monastery.

Birgitta had wished to be first taken to the San Lorenzo in Panisperna convent in Rome after her death, but due to the crowds gathered at her home, she was brought there four days later. Her body was placed in a simple wooden coffin, sealed, and placed in a marble chest. In accordance with the custom of the time, her bones were separated from the soft tissues while awaiting transport to Sweden. The convent kept an arm and some small pieces of the skeleton.

Her daughter Katarina ensured the body was returned to Sweden. The journey took seven months across Europe, over the Alps to Poland, then by boat to Öland, and finally to Söderköping. Through Östergötland, the coffin was carried in procession to Vadstena. Many miracles were reported along the way.

The wooden coffin with iron fittings that carried Birgitta’s body during the journey is now in the Sancta Birgitta Monastery Museum in Vadstena.

Birgitta becomes Saint Bridget

In 1391, Birgitta was canonized by Pope Boniface IX in Rome, officially recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church. She became one of Europe’s most famous saints, and her monastic order, the Bridgettine Order, spread to several countries. The Vadstena monastery became a major center for both religious and cultural life during the Middle Ages. After the Reformation, the monastery’s activities declined, eventually closing in 1595. Saint Bridget is today one of Europe’s three female patron saints.

Katarina, Birgitta’s daughter

Of all Bridget’s eight children, we know most about her daughter Katarina. Katarina married but then accompanied her mother to Rome. She never saw her husband again, as he died a few years after their arrival in Rome. Katarina was 41 when her mother died and eventually became the first abbess of Vadstena Monastery, dying herself only eight years later, in 1381.

Much of what we know comes from a biography written at Vadstena Monastery in the early 15th century, based on oral memories of Katarina and personal recollections of monks and nuns.

Katarina’s remains were laid together with her mother’s relics in Vadstena in August 1489, nearly a century after her death.

Saint Bridget in the collection Swedish History Museum

At the Swedish History Museum, there is a small gilded copper box—a reliquary. According to the inscription, the wood inside comes from the table where Birgitta ate her meals and perhaps died. This shows how strongly people believed in her holiness. The museum also houses textiles from the Bridgettine sisters in Vadstena, embroidered with silk, gold, and religious motifs, used to adorn churches. Many wooden sculptures depicting Saint Bridget are also preserved.

Saint Bridget’s attributes, her identifying symbols, are the goose quill, inkwell, and the book of revelations. These items almost always appear in depictions of her.

Bridgettine textiles

At Vadstena monastery, the Bridgettine sisters produced various textiles. When planning the monastery, Birgitta wanted the workroom to have bright windows and good chairs to facilitate textile work. Everyday attire was simple, but for God’s glory and church decoration, textiles were lavish, using silk, gold and silver thread, satin, and pearls.

The visual language was rich and narrative, depicting Mary, her parents, Mary and her son, and Christian symbols. Red, the color of martyrs and love, dominated. Illuminated manuscripts from the monastery library likely inspired the embroidery. During the Reformation, some textiles were removed from the church, sold, or donated. Today, only a few remain in Vadstena or at the Swedish History Museum.

Film about medieval church textiles from the time of Saint Bridget. Production: the Birgitta Foundation and the Swedish History Museum.

Reliquary

In the Swedish History Museum, a small gilded copper box is engraved with Saint Bridget on the front. She wears a richly folded cloak falling in hard folds at her feet, dressed as a respectable married woman of the Middle Ages, hair and chin covered. She holds a large cross in her right hand and an open book in her left.

Reliquary box

Depiction of Saint Bridget as a pilgrim.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Sveriges historia

The small box, which is 8.8 centimetres long and 5.1 centimetres wide, opens at the bottom and has a trefoil-shaped carrying loop on top. A Latin inscription on three sides reads: “de mensa S birgitte (vidu)e de regno schwecie”, meaning “from the table that belonged to the widow Saint Bridget of the Kingdom of Sweden.”

The box is a reliquary for a piece of the holy Bridget’s table. While it may seem odd that a table is a relic, tradition holds that Saint Bridget died on it. She also used the table with her family for meals at the house on Piazza Farnese and received many visions there, possibly writing them down.

The reliquary in the collections of the Swedish History Museum is now empty, but a similar one in Aachen, Germany, still contains a dark brown, worm-eaten piece of wood, likely walnut.