Rings from the Iron Age

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Exotic and precious finger rings could have been acquired by Scandinavians through raids on the continent, but they may also have been given as personal gifts, symbols of fidelity and loyalty during times of social and political insecurity.

One of Sweden’s finest Roman finger rings was found in 1862, when a labourer named Johan Peter Lundqvist was digging in a gravel pit west of Ystad. Most rings set with semi-precious stones were likely made in the provinces of the Roman Empire, where the skill of cutting and engraving gemstones was highly developed.

Gold ring

Found in Skåne, Ystad area.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

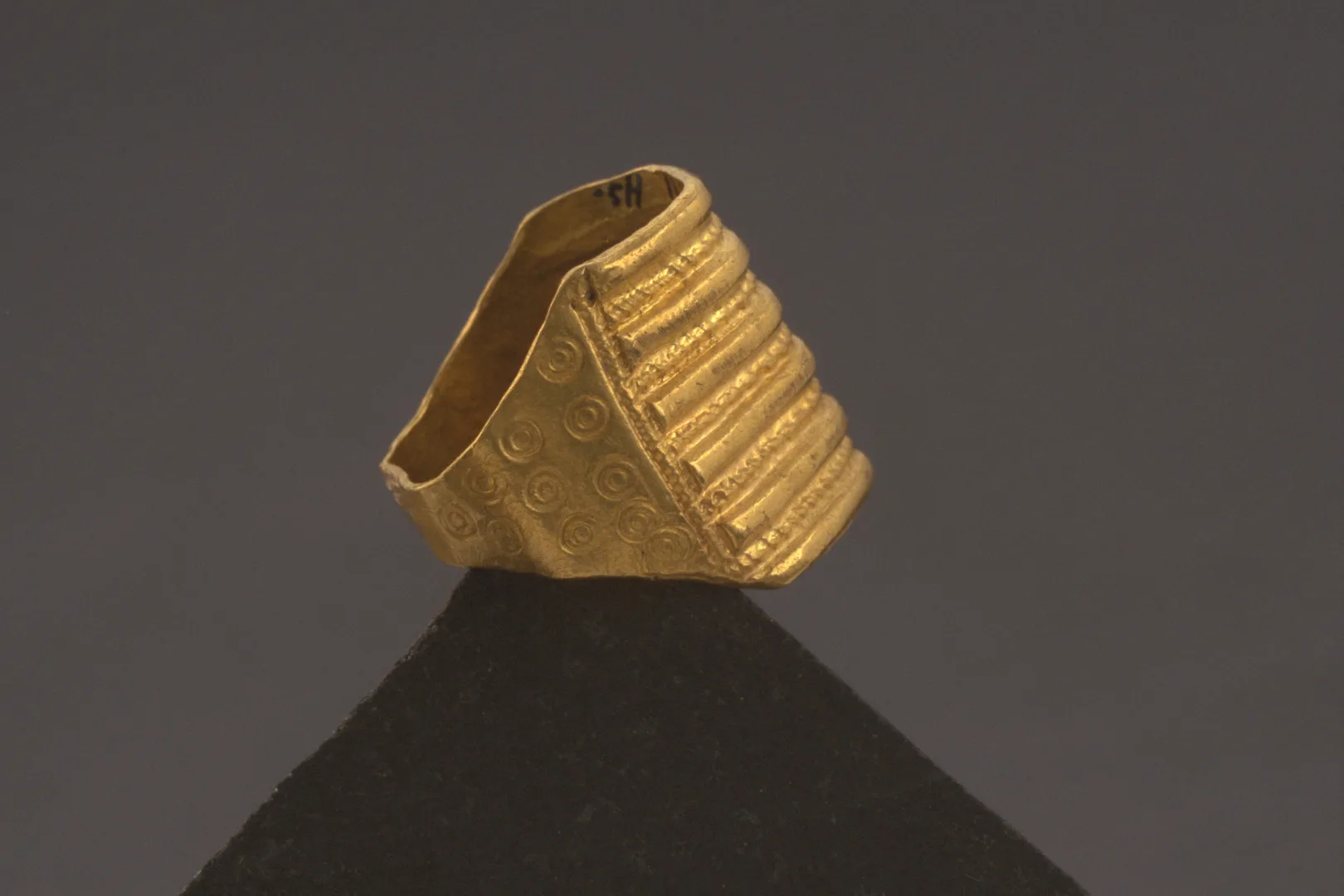

Ring from Hälsingland

Eighteen rings of this kind have been found in Scandinavia. In addition to this one from the wealthy Hög region, others have been discovered along the coastlines of Halland, Bohuslän, and Gotland.

Hög, near present-day Hudiksvall, was a power centre during the Roman Iron Age. In large burial mounds, archaeologists have uncovered Roman imports. The area’s wealth likely stemmed from iron production.

The composite ring bands, with filigree wire between the layers, allowed the ring to grow vertically without restricting the wearer’s finger movement.

Gold ring

Found in Hälsingland, Hög parish, Glimsta village, Västigården

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

A Roman ring

A jeweller in Stockholm purchased this ring, with its flat-cut carnelian, in 1872. He had bought it from a travelling trader, who likely acquired it during a parish visit. It was probably found in Vackerby, Frustuna parish, Södermanland.

In the Nordic region, 26 rings with set gemstones or glass paste imitations have survived. Of the seven found in Sweden, two are from Södermanland. These rings were most likely crafted in workshops under Roman control. They may have been gifts from Roman commanders to victorious warriors.

Gold ring

Found in Södermanland, Frustuna parish, Vackerby.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

The snake ring from Kville

Realistic snake finger rings, bracelets, and necklaces were popular among Greeks and Romans. These rings may also have been used as weights or weight standards for measuring out quantities of gold.

Scandinavian Germanic tribes simplified and adapted the snake motif. The snake symbolised immortality and fertility. It was also dangerous and awe-inspiring, qualities that made it an effective protector against evil.

Grave finds show that both men and women of the social middle class wore such snake rings between 150 and 350 AD. This particular ring was discovered in the 19th century in Kville, Bohuslän, a region rich in Iron Age artefacts and significant in western Scandinavian history.

Snake ring

Found in Bohuslän, Kville parish, Solhem, Mellangården.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

The gold of Skedemosse

One of the most important sacrificial sites on Öland was Skedemosse. Offerings included coiled snake-headed rings and finger rings.

In total, over one kilogram of gold was recovered from the drained peat bog. On several occasions, newly made or unused spiral-shaped snake rings were deposited. Ten Roman silver coins (denarii) were also discovered during excavations between 1954 and 1964.

The bog was primarily used between 200 and 400 AD for sacrificing war spoils, such as broken weapons and horse gear. Animal sacrifices, mostly horses, cattle, and pigs/sheep, were also made. In some instances, humans were sacrificed.

The religious customs of Celts and Germanic peoples were similar. Julius Caesar, in his account of the Gallic Wars, describes how the Gauls vowed the spoils of war to their war gods before battle. Skedemosse appears to have been used over long periods for both war-related sacrifices and peaceful offerings to the gods.

Gold rings

Found in Öland, Gärdslösa parish, Skedemosse.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

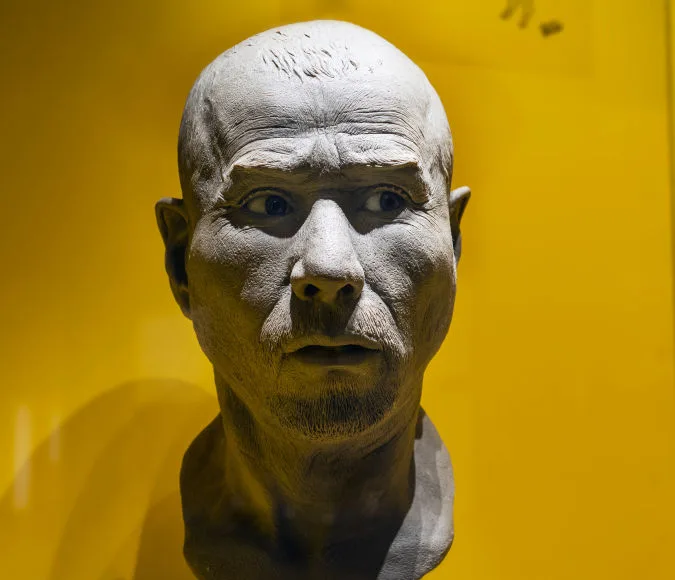

The chieftain of Lilla Jored

The significance of gold finger rings was immense. In early Rome, only the king and certain high priests were allowed to wear them. Later, they became a symbol of aristocratic rank.

When Emperor Septimius Severus, in AD 197, allowed common soldiers to wear gold rings, the symbol lost its exclusive status within the Roman Empire. It is likely that Germanic chieftains and kings adopted the tradition of gifting such rings to allies, or as rewards to warriors.

These two rings were found in one of Sweden’s richest chamber graves, excavated in 1816 in Lilla Jored, Kville parish, Bohuslän. The grave also contained a magnificent sword, glassware, pottery, bronze vessels, and these finger rings, which adorned the chieftain’s fingers in the 4th century AD.

The chieftain's rings

Found in Bo, Kville, Lilla Jored.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet