Pendants and pearls

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

A Roman-Era pendant from Öland

The largest known pendant from Öland was found in Lerkaka on the island’s eastern coast. It measures 6.3 centimetres in height and weighs 25.5 grams. The discovery was made in 1863 by the tenant farmer Olof Larsson and his daughter, Stina Maria Olsdotter, while they were raking a barley field.

The idea for these pendants, worn by high-status women, originally came from the Black Sea region. Their characteristic pear shape emerged during the early centuries AD and was adopted in key Scandinavian centres of production.

This example features smooth filigree wire, sometimes arranged in V-shaped patterns. The same decorative style is found on double-conical filigree beads and reflects a well-established workshop tradition that continued on Öland for several generations.

Pendant from Öland

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

The Maglarp pendant

This pendant, adorned with filigree, was worn by high-born Germanic women during the Roman Iron Age, around AD 100. Filigree is a highly sophisticated goldsmithing technique in which decoration is created using fine wires and tiny gold granules.

Two of the four pendants found in Skåne are so well preserved that the filigree ornamentation can be studied in full. They may have been produced in workshops on the island of Bornholm. Like this one, some pendants from Bornholm feature smooth surfaces between the lower decorative bands of twisted wire, with no granulation.

However, the spiral wire around the neck portion of this pendant does not match Bornholm’s typical style. It may have been crafted in a local Skåne workshop influenced by Bornholm techniques. The pendant was added to the museum’s collection in 1858 from the estate of the Reverend M. Bruzelius.

Pendant from Maglarp

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

A filigree bead from Runsten

A double-conical bead made of gold foil was discovered by the farmhand Olof Fredrik Jaensson in 1876 while ploughing a field on Öland.

Like the pendants, both the form and craftsmanship of the bead trace back to traditions originating in the Black Sea region. The bead is decorated with granulated gold, as well as smooth, beaded, and twisted filigree wire arranged in a herringbone pattern.

Bead from Runsten

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

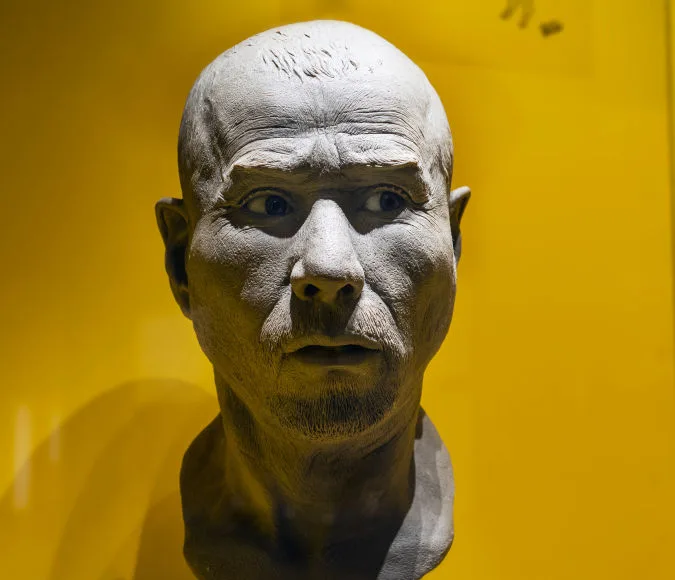

Face in a bead

This Roman-era bead, featuring a yellow, somewhat distorted face, was found in a marsh near Lärbro Church on Gotland. How it ended up there remains unknown.

The technique used to produce this type of bead is called millefiori, meaning “a thousand flowers.” It is thought to have originated in Egypt just before the start of the Common Era. The process involves fusing rods of differently coloured glass into patterned canes, which are then sliced into segments that can be reshaped into beads or other items.

In this case, the artist managed to create a miniature face from the glass canes. It is likely intended to represent the monster Medusa from Greek mythology.

Objects made using the millefiori technique were popular in the eastern Mediterranean regions of the Roman Empire. The face bead from Lärbro is one of very few of its kind found in Scandinavia and must have arrived from those southern regions.

The face bead from Lärbo

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Faces and eyes

This small silver pin, found near Borgholm on Öland, is remarkable and unique in many ways. The top of the pin forms a solid “head” around which six interlocking faces are arranged. Each face has its own nose, but they share only six eyes in total, two per pair of faces.

It may take a moment to notice, but the pin functions almost like a three-dimensional optical illusion. All six faces are bearded, in the style of ancient Greek iconography. The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD 161–180), known as “the philosopher on the throne”, was the first to revive the full beard as a fashion statement.

Elsewhere in Europe, divine figures and icons have occasionally been found with two or even four faces, but never six.

The pin was likely used as a dress pin and probably manufactured somewhere in the former Roman Empire. The head measures just about 1 centimetre in diameter, and the pin itself is 6.4 centimetres long.

The lower part is spirally grooved, though the tip appears broken. No precise find context has been recorded. It was purchased in 1907 from the antiquities dealer H. Bukowski for 285 kronor.

A needle with several faces

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet