Swedish medieval church murals

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Others were covered with limewash and later uncovered during restorations in the late 19th and 20th centuries. A few paintings escaped limewashing altogether and remain in their original state, priceless records of medieval artistic expression.

Sources of inspiration

Painters often drew inspiration from their surroundings, offering valuable insights into medieval clothing and daily life. Although the themes were typically biblical, the images provide a vivid glimpse into the medieval world. Another major source was the Biblia pauperum, or “Bible of the Poor”, a compilation of biblical illustrations from the Old and New Testaments, widely circulated in Europe from around 1460.

Despite its name, the Biblia pauperum was not a cheap book, but a visual aid used by parish priests to explain scripture. It was frequently referenced by church painters such as Albertus Pictor, who lived in Stockholm during the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

Seasonal work

Church frescoes could only be painted during the summer, when light and warmth were sufficient. In Vendel Church, two different dates, 1451 and 1452, appear in inscriptions, likely because the large church interior could not be completed in a single season.

The earliest 12th-century churches show clear Byzantine influence. Early Swedish church painting was most influenced by Denmark and northern Germany, and initially carried out by foreign artists. Over time, native masters and local painting schools emerged.

Painters undertook various tasks: decorating churches and altarpieces, painting and gilding wooden sculptures, essentially anything requiring a brush. For example, Morten the Painter in Stockholm gilded candlesticks and painted bedroom walls when not working on churches. Many painters also practised other crafts, such as carpentry, glassmaking, or embroidery.

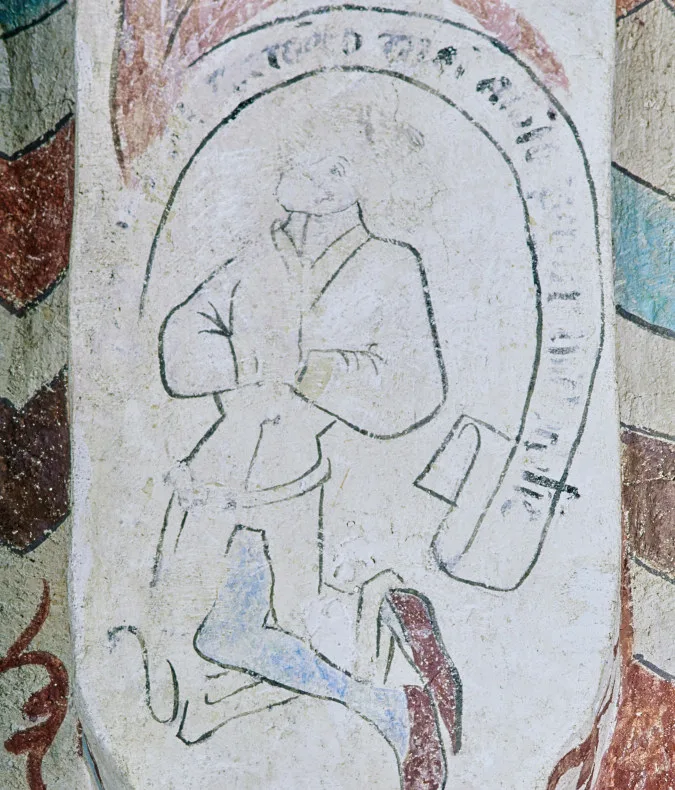

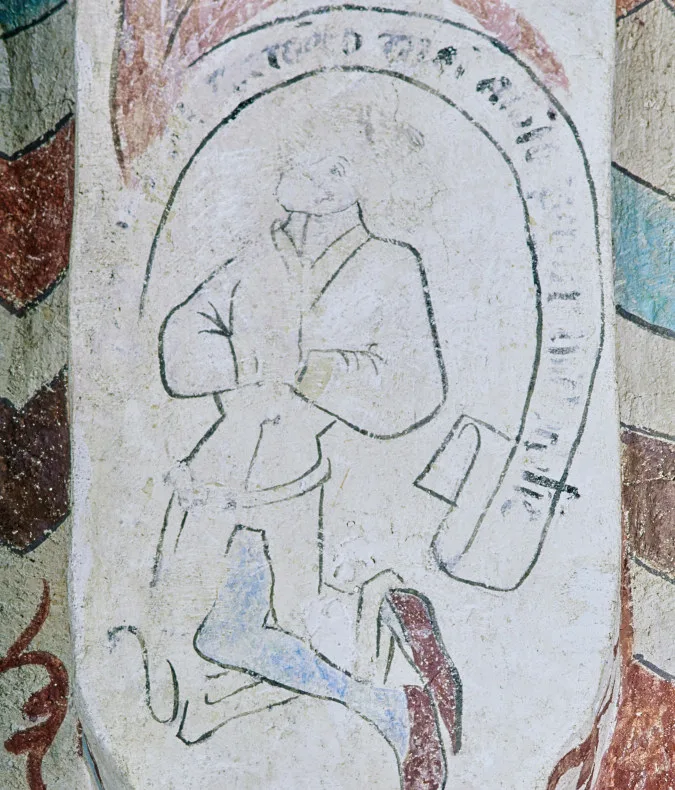

Albertus Pictor's signature, lime painting in Lid church, Södermanland. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC-BY 4.0).

Albertus Pictor

Little is known about individual artists, especially from earlier periods. From the late 15th century, records in Stockholm’s city books and tax rolls provide more information, as do similar sources from towns like Arboga. Painters likely lived in the towns where their workshops were based, typically consisting of a master and two journeymen or apprentices. Working conditions for rural painters remain largely unknown.

Albertus Pictor, originally named Albrekt Immenhusen, is perhaps the most renowned. Believed to have immigrated from Germany, he became one of Sweden’s leading painters in the late Middle Ages. He worked across the country, mainly in the Mälaren region.

In Lid Church in Södermanland, Pictor painted a self-portrait with a prayer inscribed: “Have mercy on me, Albert, painter of this church.” This may be his signature.

One of his most famous works is the frescoes in Härkeberga Church in Uppland, just north of Enköping. These vault paintings were never limewashed and are exceptionally well preserved. Many motifs are drawn from the Biblia pauperum, including Old Testament stories that foreshadow events in the life of Christ.

Who commissioned the paintings?

Church decoration was expensive. It was funded by a donor, or founder, often as an act of penance. Good deeds were believed to bring forgiveness for sins, and donating to the church ensured the donor would be remembered.

According to the Church Ordinance in the Uppland Law, farmers needed the bishop’s permission to build a church. They would then gather for a parish meeting to divide labour and transport duties according to their means.

An inscription from the mid-13th century in Anga Church on Gotland shows this method was common elsewhere, and that paintings were considered part of the church’s construction. A medieval church was not complete until its walls and ceilings were painted, stained glass windows installed, and all sculptures, stone and wood, painted and gilded.

Atoning for One’s Sins

In the late Middle Ages, the practice of indulgences began to decline. Indulgence meant that confession and forgiveness alone were not enough. One also had to demonstrate remorse through action, known as penance. It was believed that dying before completing one’s penance resulted in a period of purification in purgatory, delaying entry into paradise.

This could be avoided through good deeds. Praying before sacred images, undertaking pilgrimages, or contributing labour or money to the construction or furnishing of a church were common acts of penance. As a result, churches received numerous paintings, altarpieces, and liturgical garments from repentant sinners.

The deeply human desire to highlight one’s good deeds could benefit future generations. Many churches bear clear traces of donors through inscriptions, coats of arms, or even portraits. When donors depicted themselves, it was usually in modest scale, kneeling before Christ or Mary, often in the chancel or another prominent location.

Portraits served another purpose: by including themselves in the image, donors hoped to remain present until the end of time, when they would stand before their judge.

One such image is found in Tensta Church, depicting the nobleman Bengt Jönsson Oxenstierna. He is shown in armour with a fashionable bell strap down his back. Among the saints, he appears in smaller scale and without a halo, humbly kneeling toward the eastern altar.

Bengt Jönsson Oxenstierna presenting his coat of arms before St Peter. Lime painting in Tensta church, Uppland. ID 941361. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC-BY 4.0).

Medieval comic books: teaching through images

Medieval church frescoes could be likened to religious comic books. Just as modern comics follow visual conventions, so did these paintings. Their composition was often similar across churches, making them effective tools for religious instruction.

The content of these frescoes was fairly standard in terms of subject matter and placement. During the Romanesque period, Christ in Majesty (Majestas Domini) was always painted in the eastern apse—the semicircular space with a half-dome behind the altar in most medieval churches. In the Gothic period, this space often featured the Throne of Grace, an image of God the Father holding his crucified Son (with or without the cross), and the Holy Spirit as a dove hovering above. This was a visual attempt to explain the Trinity, which was otherwise abstract and difficult to convey in words. The holier the subject, the closer it was placed to the altar.

Another common apse motif was the Coronation of the Virgin, which became increasingly popular in the 13th century, reflecting Mary’s growing importance in Christian doctrine. A widely depicted scene in the later Middle Ages was the Mass of Saint Gregory.

Crowing of Mary. Lime painting from Sölvesborg church, Blekinge. ID 9105909, 9105906. Photo: Lennart Karlsson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM, (CC-BY 4.0).

According to legend, during Mass, Pope Gregory was about to distribute the Eucharist when a woman laughed, saying, “Surely Christ cannot be in that bread. I baked it myself this morning.” At that moment, Christ appeared above the altar and revealed his wounds to all present.

More moralising themes were also common, such as the Last Judgement and warnings against immoral living.