Large rings of gold

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

A snake-head ring weighing 191 grams was discovered in 1834 in newly cultivated land near a lake. These types of snake-head rings typically weigh between 190 and 200 grams, which suggests the gold may originally have come from coins with standardised weights.

The ring dates to the Roman Iron Age, around AD 200. The Arab diplomat Ibn Fadlan described the Vikings in Bulgar along the middle reaches of the Volga River, though his account is some 700 years younger than the Börstil neck ring:

Around their necks they wear collars of gold or silver. For every man who possesses ten thousand dirhams (Arabic silver coins), his wife receives one collar; with twenty thousand, she gets two, so that every ten thousand means another collar. Often a woman owns many such collars

Gold ring

Uppland, Börstil socken, Långalma

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

A snake-head ring

In 1873, a farmhand named Catharina Norrby found a snake-head ring while ploughing in Gotland. It weighed 183 grams, and she received 500 riksdaler in compensation.

This Scandinavian type, with simple knobs instead of lifelike snake heads, is more common. As most have been bent, likely as part of ritual offerings, it is often difficult to determine whether they were originally worn around the neck or arm.

Some snake-head rings are of very high gold content and nearly identical weight. They also appear to be newly made, lacking the wear marks that soft gold typically acquires when worn. This has led scholars to propose that such rings may also have served as bullion or a form of payment. They can be dated to around AD 200.

Gold ring

Gotland, Fole socken, Lilla Ryftes, Vätåker

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

Neck ring from Frustuna

In 1842, farmer Pehr Henriksson discovered a gold neck ring beneath a large stone in a field ditch. The site lies in Södermanland, along an ancient waterway connecting the coast to the interior. Further out toward the sea, at Tureholm, one of the country’s largest treasure hoards was found in the 18th century.

The 131-gram neck ring had been straightened, as is often the case with sacrificial jewellery. It may have been an offering to Odin, the god of the dead, ritually destroyed to ease the passage into the next world.

The neck ring features a pear-shaped clasp of continental Germanic design. Originally, the pear-shaped end fitted into a capsule-like locking mechanism, in which the ring was secured by pressing a loop into a socket.

Gold ring

Södermanland, Frustuna socken, Vackerby

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

Two snake rings from Hjälsta in Uppland

In 1891, C.G. Carlsson uncovered a pair of spiral arm rings with simplified snake heads while ploughing.

Similar arm rings have been found in skeleton graves rich in Roman imports and luxury goods in both Denmark and Sweden. This suggests that Hjälsta may also have had a local elite around the beginning of the Common Era who wore such jewellery as a symbol of status.

Further evidence of the area's importance came in 1906, when a Roman finger ring set with a carnelian was discovered in the same potato field. The site is also named Tuna or Tunalund, a toponym frequently associated with Iron Age centres of power.

Gold ring

Uppland, Hjälsta socken, Tunalund

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

Gold ring

Uppland, Hjälsta socken, Tunalund

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

A Gotlandic arm ring

In 1712, an arm ring and three double-conical filigree beads were found. The location suggests that the items were deposited as an offering in a bog. The site is in northern Västmanland, near the river Dalälven.

This type of arm ring, with forged terminals and stamped decoration, was common on Gotland. It may have been a gift and a sign of an alliance between two prominent families from different regions.

Iron may have been a commodity of interest to the Gotlanders. In the forested areas of Dalarna, Västmanland, and Norrland, iron was extracted from red ochre, lake ore, and bog ore. This trade could explain Gotlandic interest in central Sweden. Additionally, Gotlanders maintained contact with the Continent, making them key intermediaries in long-distance trade.

Gold ring

Möklinta socken, Hede, Vretmossen

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

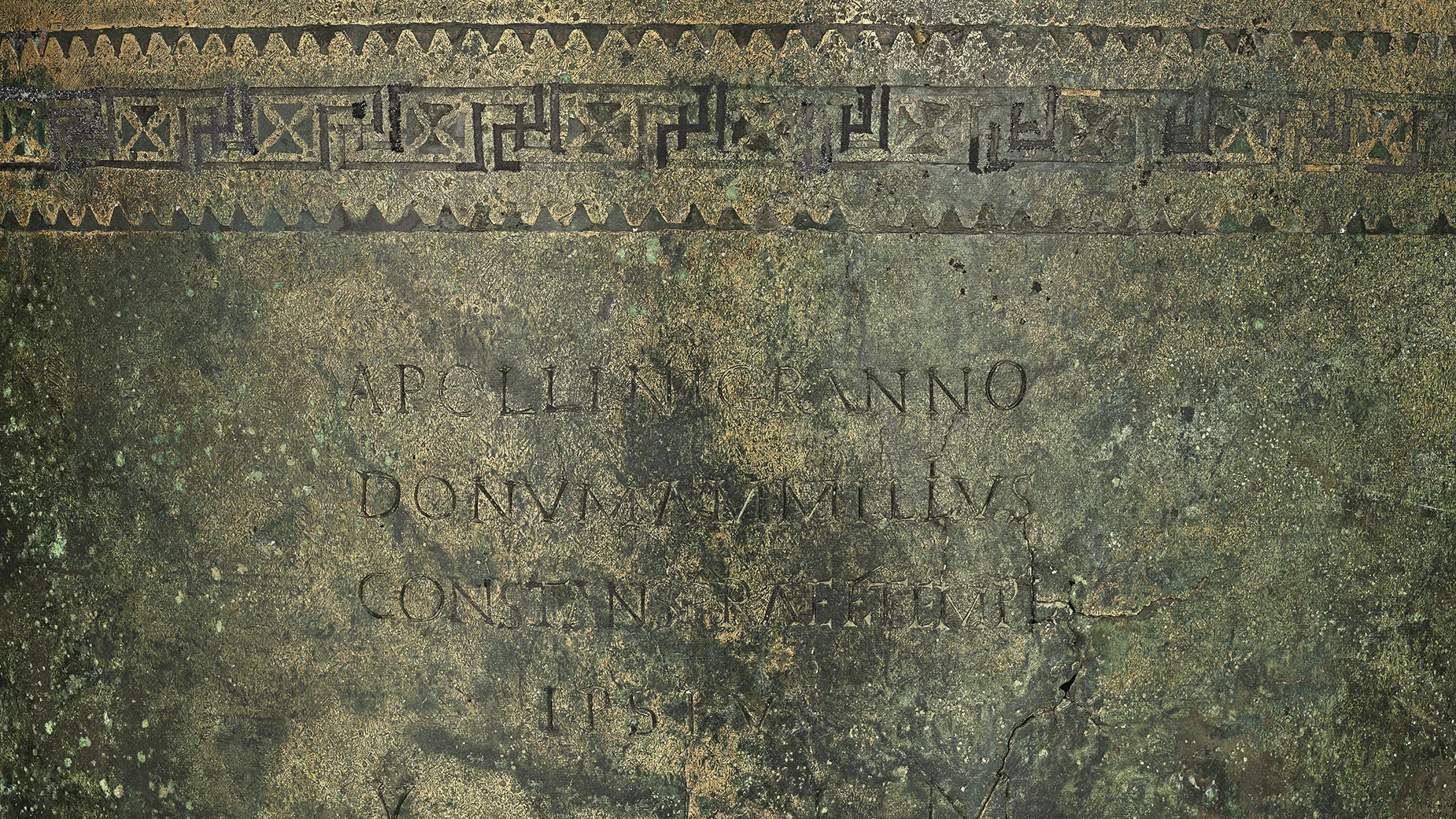

Gold neck ring from Ravlunda

In 1936, tenant farmer Sture Abraham Johansson discovered a bent gold neck ring during agricultural work between bedrock boulders in southeast Skåne. The ring’s form is foreign to Nordic goldsmithing traditions.

Similar silver neck rings with so-called capsule clasps have been found in eastern Slovakia, and in former East Prussia (today’s Kaliningrad Oblast), where they were made of bronze. These are thought to be related to Late Antique neck rings with medallion pendants, common within the Roman Empire.

The capsule’s centre features a flat, rounded garnet, and both filigree and granulation techniques are used, styles closely associated with late Roman goldsmithing. This makes it likely that the ring was crafted in the Roman province of Pannonia, in present-day Hungary, during the 5th century AD.

Filigree is a technique in which fine gold wires and grains are used for decoration. Granulation involves using only tiny gold granules as ornamentation.

Gold ring

Skåne, Ravlunda socken, Burahus

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

A snake around the neck

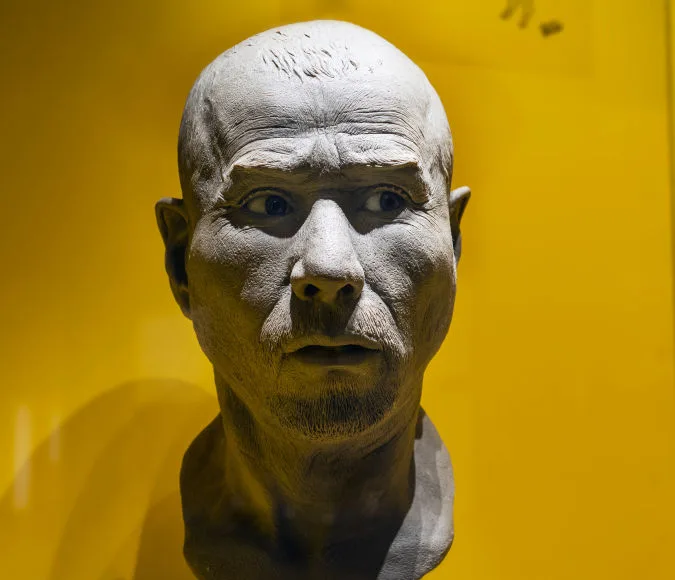

In 1868, Jöns Olsson unearthed a 136-gram gold neck ring while working in a field in Skåne. Unlike the more common snake-head rings with knobbly ends, this one features unusually lifelike snake heads. The zigzag pattern on the back even makes it possible to identify the species as a European adder.

Snake-themed jewellery was popular with both men and women in Ancient Greece and Rome. Roman gravestones sometimes depict snake-head arm and neck rings, and written sources tell us that brave soldiers were rewarded with such items.

The snake, as a symbol, is both menacing and protective - believed to guard its wearer from demons and evil forces. At the same time, it symbolises good fortune, longevity, immortality, and fertility.

Gold ring

Skåne, Stenestad socken, Stenestad

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

Snake-head ring

In 1905, F. Andersson discovered a 202-gram snake-head ring while working on a canal project on a hillside by the Kalmar Strait on the Småland coast. He was awarded SEK 500 for the find.

These snake- or animal-head rings are often found alone as votive offerings, or together with other gold in hoards.

Their form may have originated as a form of currency in a metal-based economy, perhaps even based on the Roman weight system of the pound. At the same time, grave finds, especially in Denmark but also at Tuna in Badelunda parish, Västmanland, show that they were worn as neck rings or spiral-wound arm rings by the hird, the armed retainer of local chieftains, the second-highest social tier in Iron Age society.

Gold ring

Småland, Söderåkra socken, Ragnabo

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet