Intro to the Nordic Iron Age

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

During the Iron Age, life in Sweden changed as people began producing iron from bog ore and red earth. In the collections of the Swedish History Museum, there are traces from this time, such as a woven wool garment from Västergötland, Roman glass and jewellery like fibulae — pins used to fasten clothing.

Other objects, such as swords, spurs and beads, tell stories of warriors, contacts with the Roman Empire, and how different people lived and were buried. Through these objects, we can learn more about how people in the Iron Age thought, dressed and built their lives.

Reconstruction of Nordic Iron Age clothing. From the filming of The Archaeologist's Daughter (UR, 2018) at Eketorp Fort, Öland. Photo: Linda Wåhlander, the Swedish History Museum/SHM.

The Iron Age in southern Sweden

During the Iron Age, people began producing iron from red earth or lake and bog ore. The iron was used to make tools and weapons. At first, when iron was still rare and valuable, it was also used to create decorative clothing jewellery. No longer relying on the bronze trade meant that long-distance contacts became less common in the early part of the period.

Most of the population in what is now Sweden — except in the forest and mountain areas of Norrland and Dalarna — were farmers, livestock keepers and lived in permanent settlements.

The period is long and lasts until the end of the Viking Age. Most of what we know about the Iron Age comes from archaeological excavations. We can also learn about the landscape, climate and farming by analysing pollen preserved in peat layers in wetlands.

Around AD 100, written sources begin to appear. Some are Roman writers mentioning Scandinavia, and some are short runic inscriptions carved here in Scandinavia. Written sources become more common, but it is only after the Iron Age that they give a fuller picture of life here.

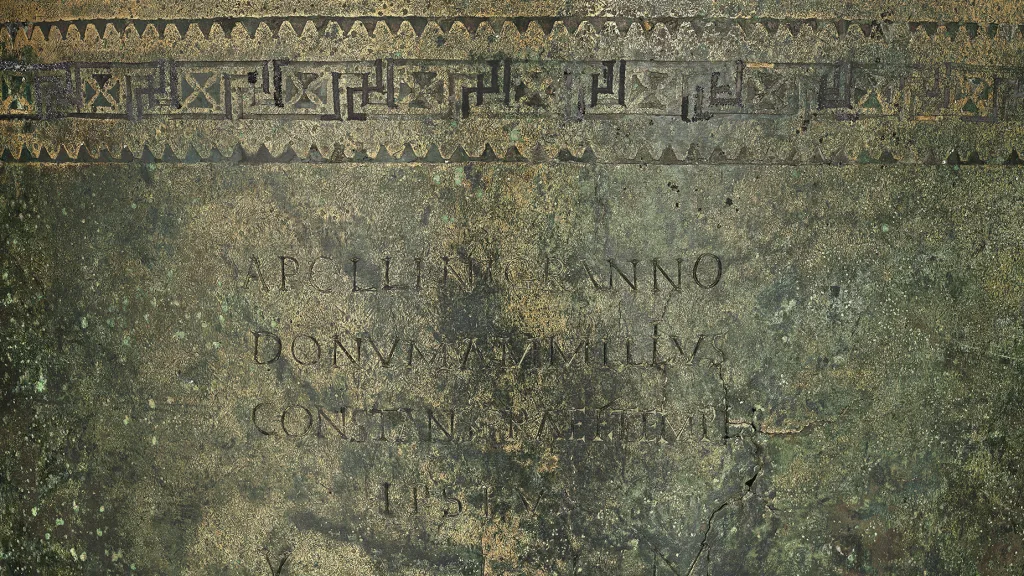

Wooden bucket with bronze bands

The bucket is formed from a series of staves, held together by four wide bronze bands that were originally gilded. The rim is also reinforced with a gutter-shaped, bent bronze sheet. Found in Ottarshögen, Uppland province, Sweden.

Iron Age brooch

Gilded silver sheet brooch with a rectangular headplate. Found in Skåne province, Sweden.

Early Iron Age in southern Sweden and the northern coasts

The period between 500 BC and AD 400 is called the Early Iron Age. North of Skåne, the Early Iron Age is usually said to continue until AD 550.

The boundary between the Early and Late Iron Age is based on the division of the Roman Empire into two or three parts in AD 395. Around the same time, animal ornamentation begins to appear on objects from Scandinavia and northern Germany. Germanic animal ornamentation, which was first inspired by Late Roman art, became one of northern Europe’s contributions to art history.

The transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age did not just mean abandoning bronze as the metal for tools and weapons — it also brought major changes to society as a whole.

In the past, the earliest Iron Age was often called the "the period without finds". People believed that much of the population had migrated away and archaeologists wondered why so few graves or artefacts were discovered. Today we now know that there were many settlements during the earliest period, but richly equipped graves are absent during the first 300 years of the Iron Age.

Around the birth of Christ, the Roman Empire expanded into parts of what is now Germany and the Netherlands. The Roman Empire never reached Scandinavia, but the influence and impact of this great power were evident as far north as Norrland.

From this period, we today have many remains in the form of graves, settlements, and iron production sites. From around 200 BC, some of the graves began to be richly furnished with jewellery, pottery, and weapons. A new aristocracy then emerged, controlling trade and long-distance contacts.

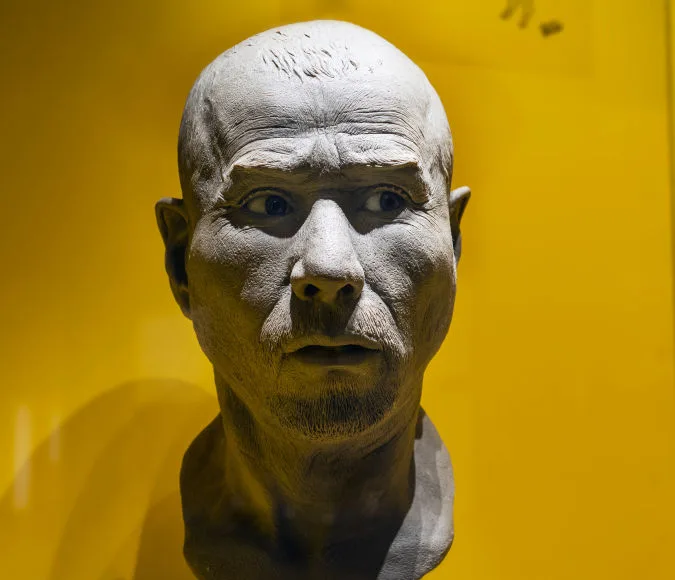

Roman face mask

Mask for cavalry games or military parades. The mask was probably hammered or partly cast. Alexander the Great was often depicted in this way: a life-sized face with flowing, curly hair. Found on Gotland island/provice, Sweden.

Pre-Roman Iron Age in southern Sweden

The period from 500 BC to AD 1 is called the Pre-Roman Iron Age. It was previously also called the Celtic Iron Age because influences from the Celtic-speaking peoples of Central and Western Europe can be seen in the Swedish material.

Across the country, people began producing iron on a large scale from bog ore and red earth. The iron was made in small bloomery furnaces. This meant they no longer had to rely on importing copper and bronze.

The main livelihoods were farming and livestock keeping, supplemented by hunting and fishing. The climate had become colder and wetter. Spruce trees began to replace deciduous forests in central Sweden. The colder winters meant that animals increasingly had to be kept indoors.

Often the animals stayed in part of the same longhouse where people lived. This made it easier to collect the manure they produced, which was needed to fertilise the fields. The fields were mostly used to grow hulled barley, a grain suitable for porridge and for brewing beer.

Reconstruction of different Iron Age outfits from the Migration Period to the Viking Age. From the filming of The Archaeologist's Daughter (UR, 2018) at Eketorp Fort, Öland. Photo: Linda Wåhlander, the Swedish History Museum/SHM.

During the period 200–1 BC, some graves once again began to include richer goods such as tools, jewellery for clothing, and weapons. An important new feature was the belt, with various metal fittings and parts. The belt shows that people had started wearing trousers. Trousers, as well as the single-edged sword, were new influences ultimately coming from eastern horse-riding peoples. During this time, riding skills also began to develop, but people rode without saddles.

The oldest preserved garment from Sweden is a wool cloak from Gerum in the Västergötland province. The cloak was intricately woven with a pattern.

Gerum cloak

Found in Gerum, in the Västergötland province, Sweden.

Men’s and women’s clothing could include another new feature — the dress pin, shaped like a safety pin with a spring function. It was decorated in different ways, following changes in fashion. This type of pin is called a fibula.

The new warrior class had different equipment depending on rank. The most powerful carried swords, while foot soldiers used spears and lances. When sword-bearers were buried, their swords were often bent so they could not be used again. People may have feared that someone would dig up the sword and use it, or that the dead might return.

Iron Age sword

Single-edged sword, folded blade. Found in Hödsrum, Öland, Sweden.

Roman Iron Age in southern Sweden

The period between AD 1 and 400 is called the Roman Iron Age. Scandinavia never became part of the Roman Empire, but we were strongly influenced by the great power in the south. Roman traders probably reached Scandinavia, and many Roman goods found their way here.

We can see this through beads, bronze objects, weapons and glass found in Sweden. In addition, men from what is now Sweden served as mercenaries in the Roman army. Some of them also took part in the Germanic wars against the Romans. Those who had been on the continent and survived brought back goods, coins, customs and clothing details.

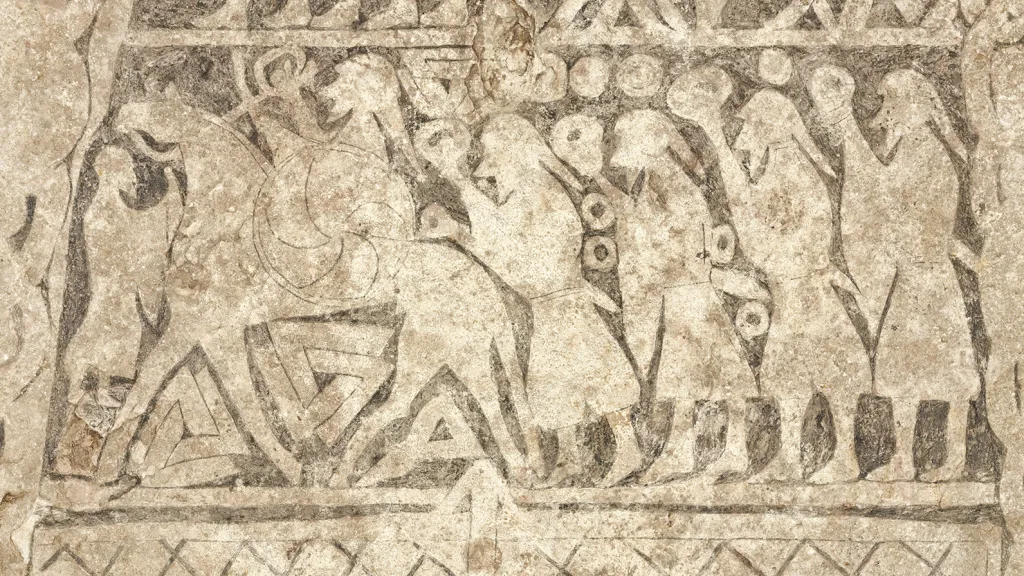

An important part of transport was the clinker-built boats. Very few of these have been found in Sweden, but they are shown on picture stones. Sails do not seem to have been used; the boats were rowed.

Across the settlements, burial grounds grew with stone settings, stone circles and standing stones. The dead were often cremated, but burials with skeletons were also common. The amount of grave goods placed with the deceased varied depending on their social status.

In the graves, archaeologists find parts of tableware such as drinking horns, pottery, wooden vessels or Roman glass. The glass was made in the Mediterranean region or around the Black Sea. Women and girls could be buried with sets of glass beads made in the eastern Mediterranean. Some were also given finely decorated belts or jewellery for their clothing.

Drinking horn

Made of glass. Found in Östervarv, Östergötland province, Sweden.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

A few men were buried with full weapon sets. Some of the finest symbols of rank were spurs for a mounted officer or a sword. Most people, however, were buried with only a simple bentwood box or with no grave goods at all.

There were many settlements, and the range of domestic animals now included chickens and cats, a result of contact with the Romans. Hulled barley was the main crop grown.

The size of longhouses also became a sign of status. The richest farmers had houses between 30 and 50 metres long. Spindle whorls and loom weights show that wool production was important.

Regional differences became increasingly clear during this time. The southernmost areas had traditions similar to those on Zealand. Western Sweden was influenced by Jutland and Norway. Öland and Gotland developed their own distinctive styles in houses, jewellery and burial customs.

Iron production increased, and people began making iron from lake ore. They also started using charcoal pits to produce charcoal more efficiently for bloomery furnaces. Out in the forests, they built tar pits to make tar for boats and houses.

Along the Norrland coast up to Ångermanland and in Jämtland, new settlements were built similar to those in the south. The settlers were farmers and livestock keepers, but iron production and hunting also attracted newcomers. These new settlers came both from the south and from the area that is now Norway.

The Iron Age in northern Sweden

Asbestos-tempered pottery and many other Bronze Age features continued to appear until about AD 100–200. After that, pottery production in the inland areas stopped. However, systems of pit traps and settlement sites show that the inland was still inhabited and used.

As early as the 200s BC, iron was being produced in Lapland in areas where hunting and fishing dominated the economy. Iron production then continued in various types of bloomery furnaces across large parts of Norrland.

In central and southern Norrland and in Dalarna, large-scale iron production began after AD 1. There, people made different types of bar iron, which were later sold to other parts of southern Scandinavia.

Inland, along lakes and rivers, so-called inland graves were built. Their locations suggest a culture based on hunting, fishing and iron production. The graves were made as round, triangular and square stone settings.

The graves look similar to those in southern Scandinavia but may have been built by a pre-Sami population. Different types of iron arrowheads show that they had a different material tradition from that in the south.

Along the coast and the lower parts of the river valleys, settlements with longhouses of southern Scandinavian style were built from the time of Christ onwards. Before AD 550, contact with Norway was important for these settlements up to Ångermanland. Large and rich burial mounds were built for chieftains.

These graves were often equipped with bronze cauldrons imported from the Roman Empire. After AD 550, the forms of objects begin to resemble those found in Svealand. These settlements had an economy where livestock keeping and grain farming played an important role.

Buckel urn

Found in a rich chamber grave in Borg, Hälsingland provice, Sweden.

Summary

Learn more about the Nordic Iron Age

At the Swedish History Museum, you can explore objects and traces left by Nordic Iron Age people in several exhibitions: Prehistories, The Gold Room, and The Viking World.