Gustav Vasa and the Reformation

The movement began in Germany in 1517, when the monk and theology professor Martin Luther publicly posted his 95 Theses in protest against the Catholic practice of selling . Luther condemned church corruption and argued that salvation could not be bought, but was granted through faith alone. He stressed the central role of the Bible and insisted that every person should be able to read and interpret it for themselves.

Martin Luther

Copper print on paper. Luther's dress is formed of sentences describing his life story in first person. The preliminary sketch is, according to the inscription, made by Lukas Cranach.

Luther’s ideas spread rapidly, met with both enthusiasm and fierce resistance. In some regions, such as parts of Germany and Scandinavia, his message resonated with rulers and monarchs who saw an opportunity to free themselves from papal authority and take control of church wealth. In other areas, such as Spain and Italy, the Catholic Counter-Reformation struck back forcefully in defence of traditional doctrine.

The Reformation also gave rise to other Protestant movements, including Calvinism in Switzerland and Presbyterianism in Scotland. This growing religious fragmentation led to conflicts and wars, notably the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), which had profound political and social consequences.

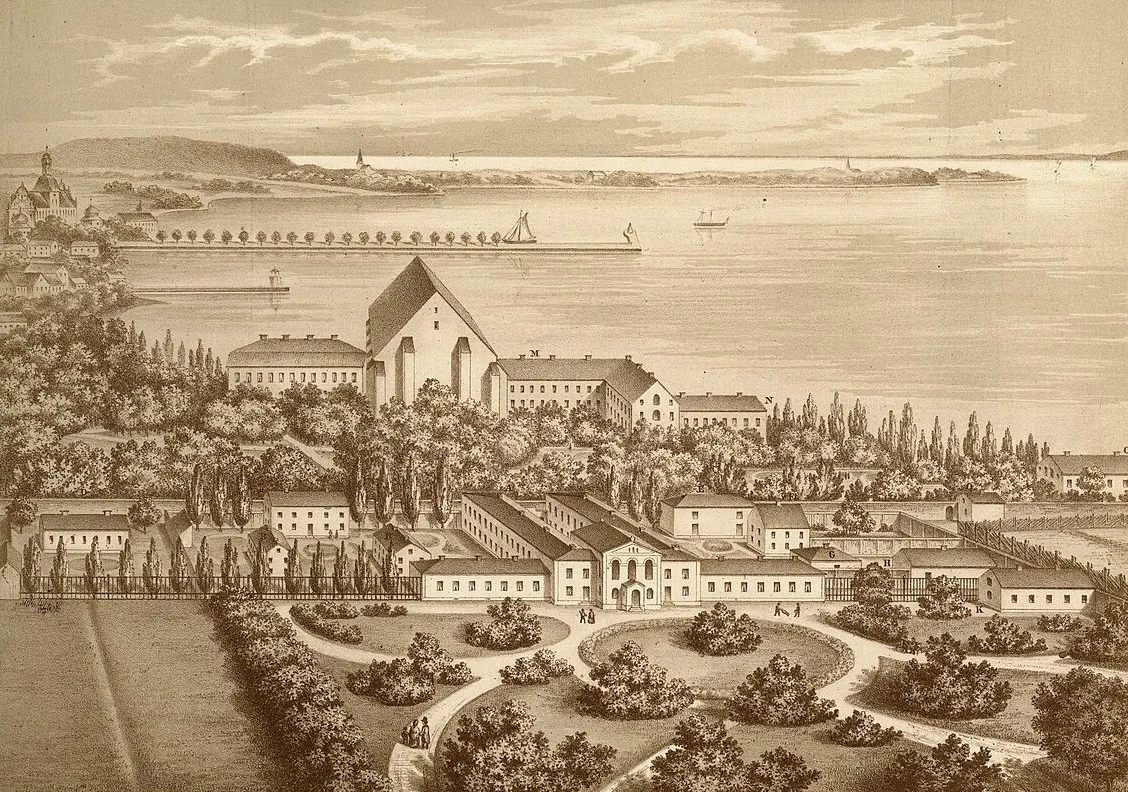

The Reformation in Sweden

In Sweden, the Reformation began when Gustav Vasa became king in 1523. Having just led a war of liberation against Denmark, he needed to consolidate power and saw the Church’s immense wealth as a way to finance his rule. Reformist ideas were already present in the country, notably through the priest Olaus Petri, who had studied under Luther in Wittenberg.

At the parliament in Västerås in 1527, Gustav Vasa decreed that the Church’s property would be transferred to the Crown, that the king would control church administration, and that sermons would henceforth be delivered in Swedish.

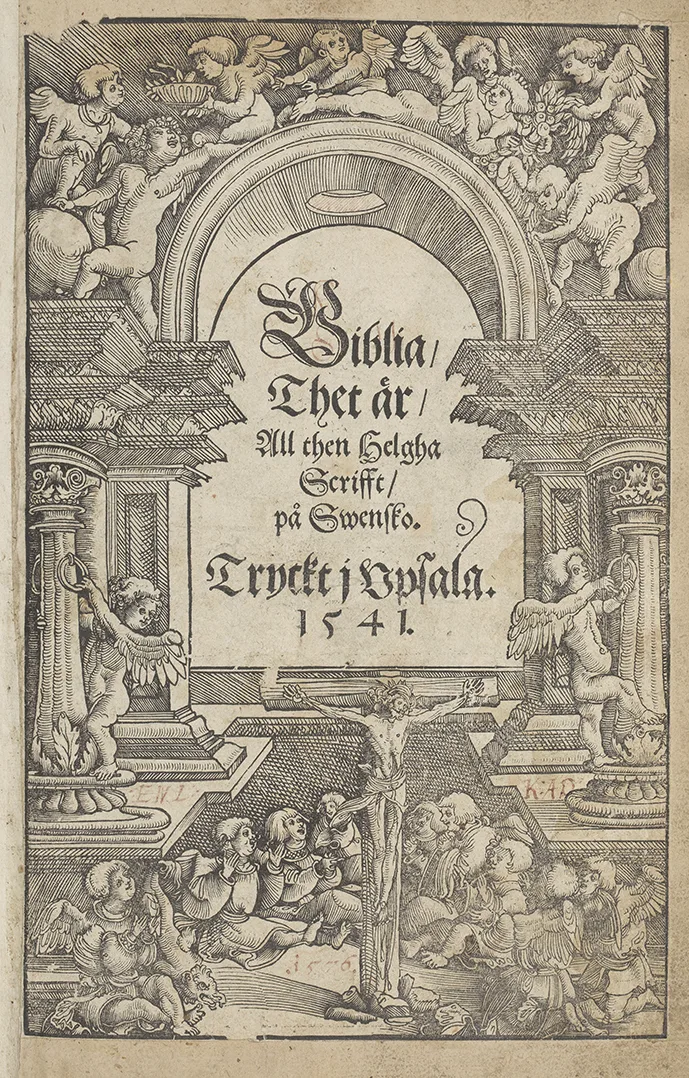

Olaus Petri and his brother Laurentius Petri were central figures in the Swedish Reformation. Laurentius became the country’s first Lutheran Archbishop in 1531. Together, the brothers worked to spread Lutheran teachings through preaching and by translating key religious texts. They published the catechism and the New Testament in Swedish, and in 1541, the full Swedish Bible was printed.

Despite these milestones, change came gradually. Many Catholic traditions persisted for decades, and it was not until later, particularly under Gustav Vasa’s sons, including Sigismund and Karl IX, that Lutheranism was firmly established as the state religion and Catholic influence fully removed.

Consequences of the Reformation

Following the Reformation, Sweden became a Protestant nation with a Lutheran church. The king assumed the role of supreme head of the church. This shift greatly strengthened royal power at the expense of the Church. The Swedish church became a tool of the state, with clergy subordinate to the monarchy.

At the same time, access to religious texts and knowledge expanded. Reading and Christian education became cornerstones of religious life, as everyone was expected to read the Bible. As a result, literacy in Sweden increased significantly.

The Swedish Reformation was thus both a religious and political transformation, a blend of Lutheran theology and Gustav Vasa’s drive for control. The outcome was a unified kingdom with a state church that would shape Swedish society for centuries to come.

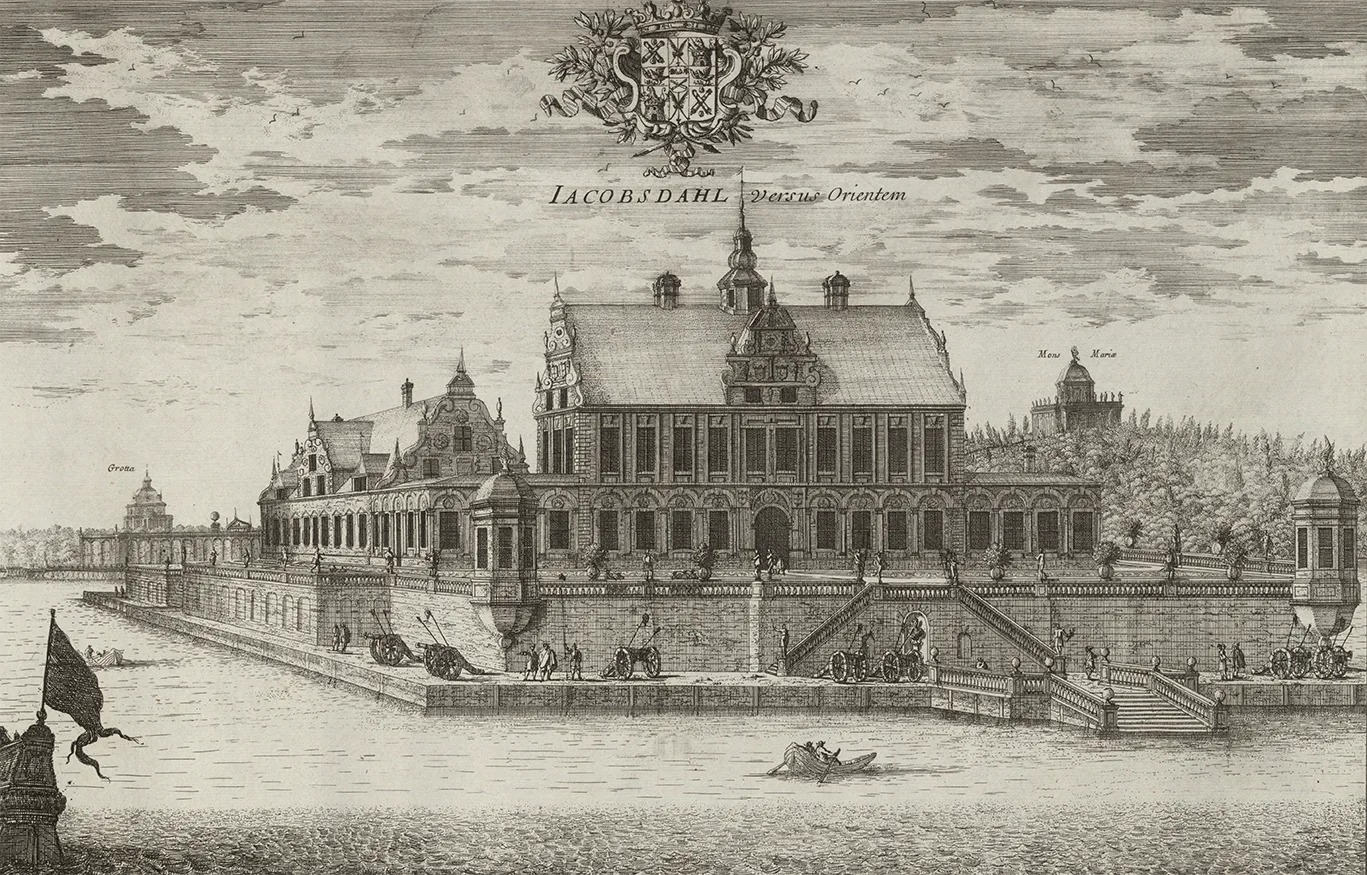

A royal prayer book

In the 16th century, the royal printing press stood at Själagårdsgatan 13 in Stockholm. In 1559, it produced a small personal prayer book containing prayers for various occasions. Many of these prayers were drawn from earlier prayer books, possibly compiled by Laurentius Petri, Sweden’s first non-Catholic archbishop.

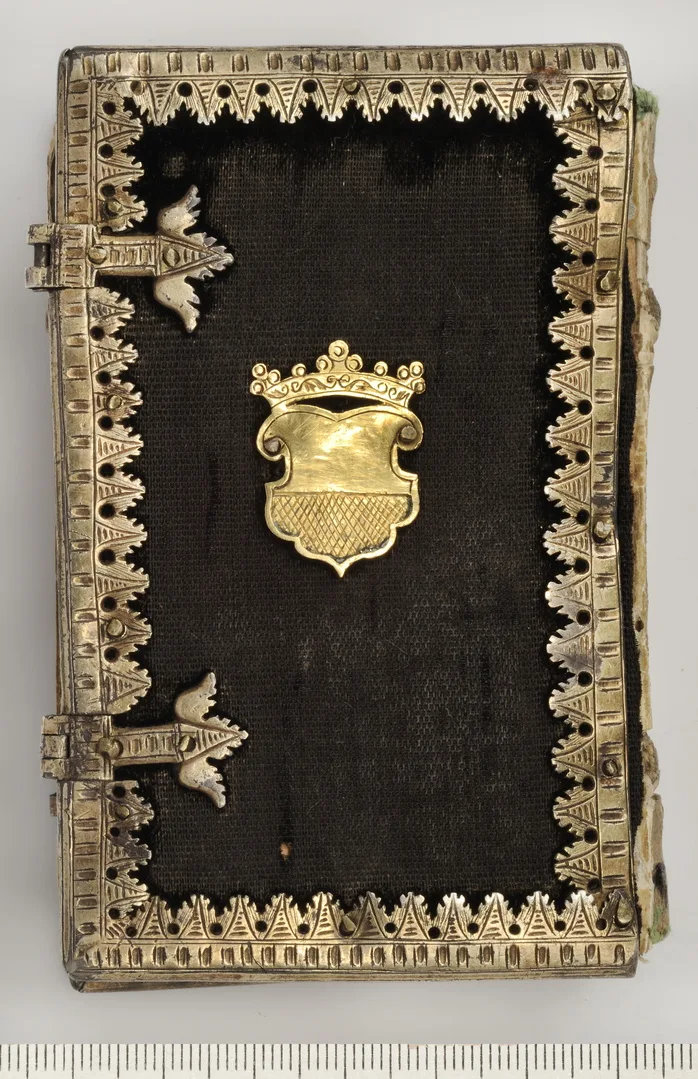

This particular copy belonged to Malin Sture, niece of Queen Margareta Leijonhufvud and cousin to King Erik XIV, Johan III, and Karl IX. Malin was born in 1539, making her 20 years old when the book was printed. The cover bears the Sture family coat of arms, suggesting it may have been passed down through the family.

The book was also used as a kind of memory book. Several of Gustav Vasa’s children and some of Malin’s siblings wrote proverbs and signed their names within its pages. In the calendar section, Malin herself noted under July 10 the last time she saw her brother Nils, who was killed by Erik XIV in 1567 during the so-called Sture Murders, in which Malin’s father Svante and her other brother Erik were also killed.

Prayer book

Book bound in black velvet and trimmed with gilded silver.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Sveriges historia