From kaftan in Turkey to chasuble in Sweden

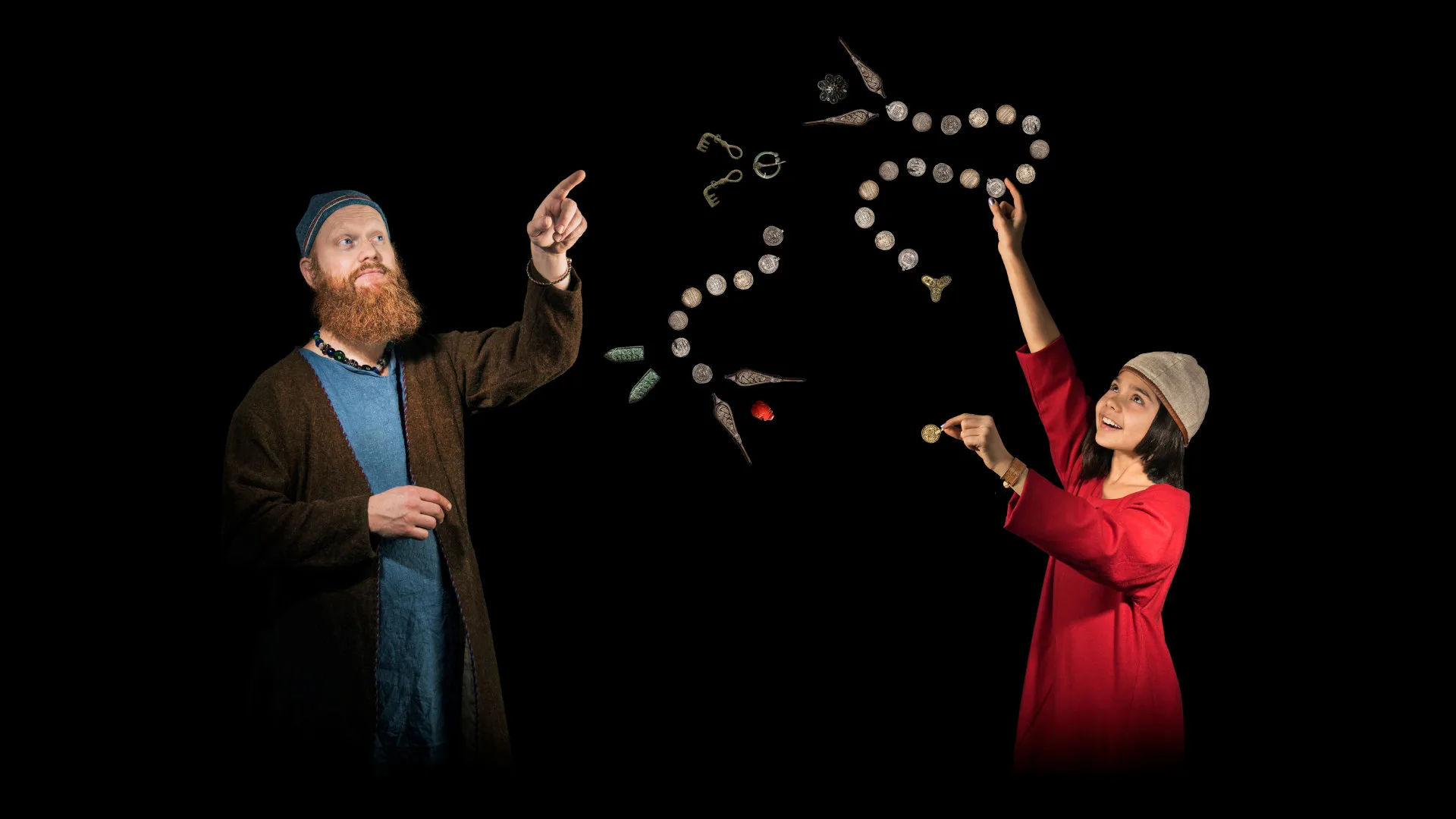

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

Among the treasures of the Swedish History Museum is a garment that originally began its life as a kaftan in Turkey. After Sweden’s ambassador to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) brought it back to Sweden in the mid-1600s, the garment was transformed into a chasuble, a liturgical vestment worn by priests during services with Holy Communion.

Chasuble

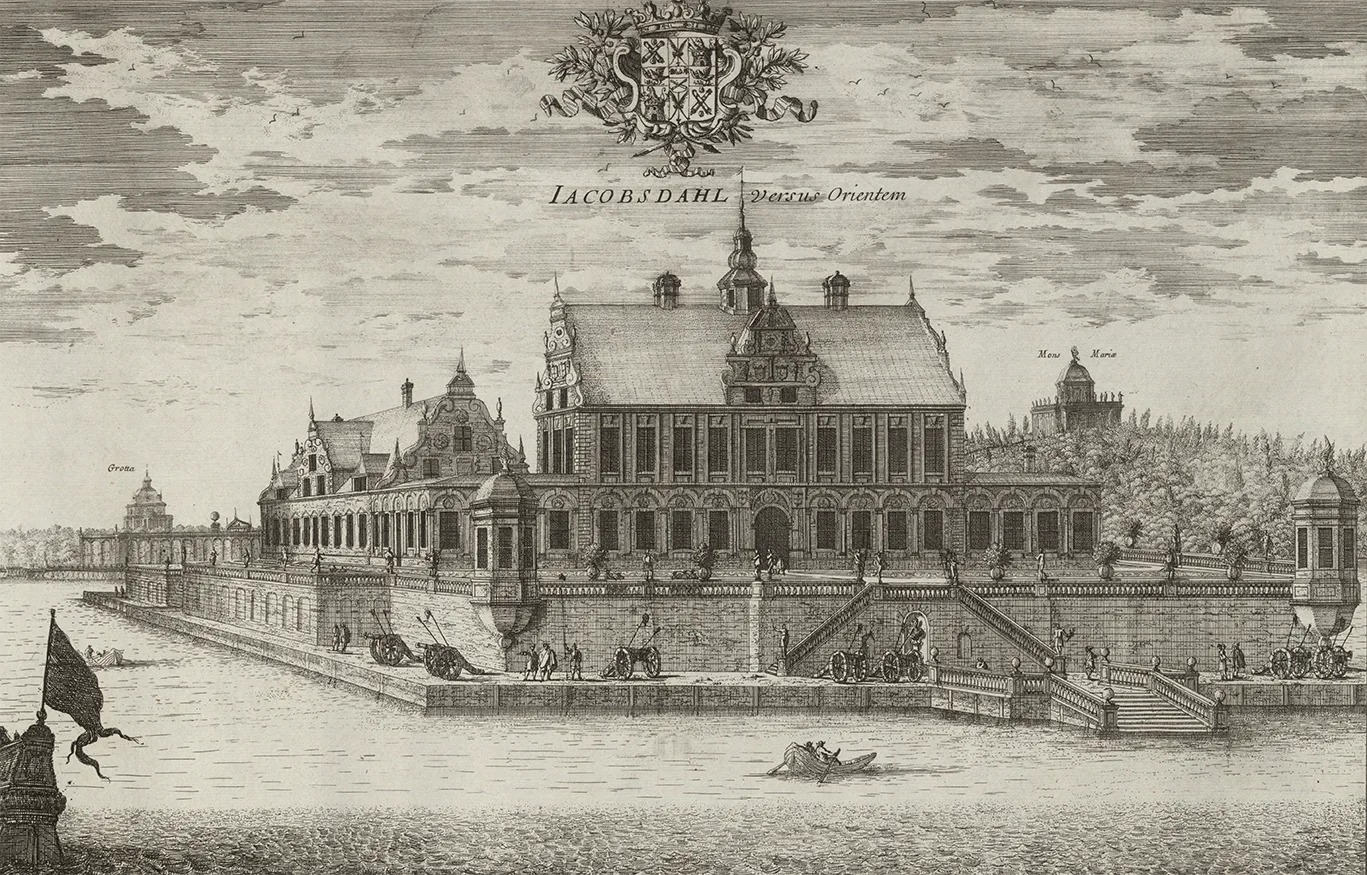

Ambassador Claes Rålamb in Constantinople

In 1657, nobleman Claes Rålamb (1622–1698) was dispatched by King Charles X Gustav as envoy extraordinaire to the Ottoman court in Constantinople. His mission was to secure an alliance with the Sultan on behalf of Sweden. The diplomatic effort ultimately failed, but Rålamb’s two-year stay left behind a rich legacy.

During his time in Istanbul, Rålamb kept a detailed diary of his experiences. In it, he recounts sampling the drink coffee, before it had reached Sweden, and visiting a Turkish bathhouse. He also describes witnessing the dance of the whirling dervishes, a Sufi Muslim order who spin in devotional movement to come closer to God.

Throughout his diary, Rålamb notes how kaftans were given as ceremonial gifts, including to himself:

Then he let hang upon me a robe of golden cloth, which they call a kaftan.

In the Ottoman Empire, kaftans were commonly given as tokens of honour.

Rålamb showed a particular interest in Turkish dress. Among the items he brought home was what is now known as The Rålamb Costume Book, a collection of 121 gouache and gilded illustrations depicting the attire of Ottoman citizens, officials, and military personnel.

Shimmering silk brocade

Among the items Rålamb brought back was also the shimmering fabric that would later become a chasuble. One theory is that it came from a kaftan gifted to him during his journey, perhaps even the "robe of golden cloth" mentioned in his diary. He also recorded purchasing textiles, such as a "blue golden cloth," which he had sewn into a letter pouch.

What Rålamb called gyllenduk in 17th-century Swedish is known as kemha in Turkish. Today, these fabrics woven with metallic threads are referred to as brocade. They shimmer in gold and silver. The pattern on the fabric Rålamb brought home features carnations and tulips. In the Ottoman Empire, tulips were associated with Allah and with paradise.

Detail of chasuble

With carnation and tulip pattern.

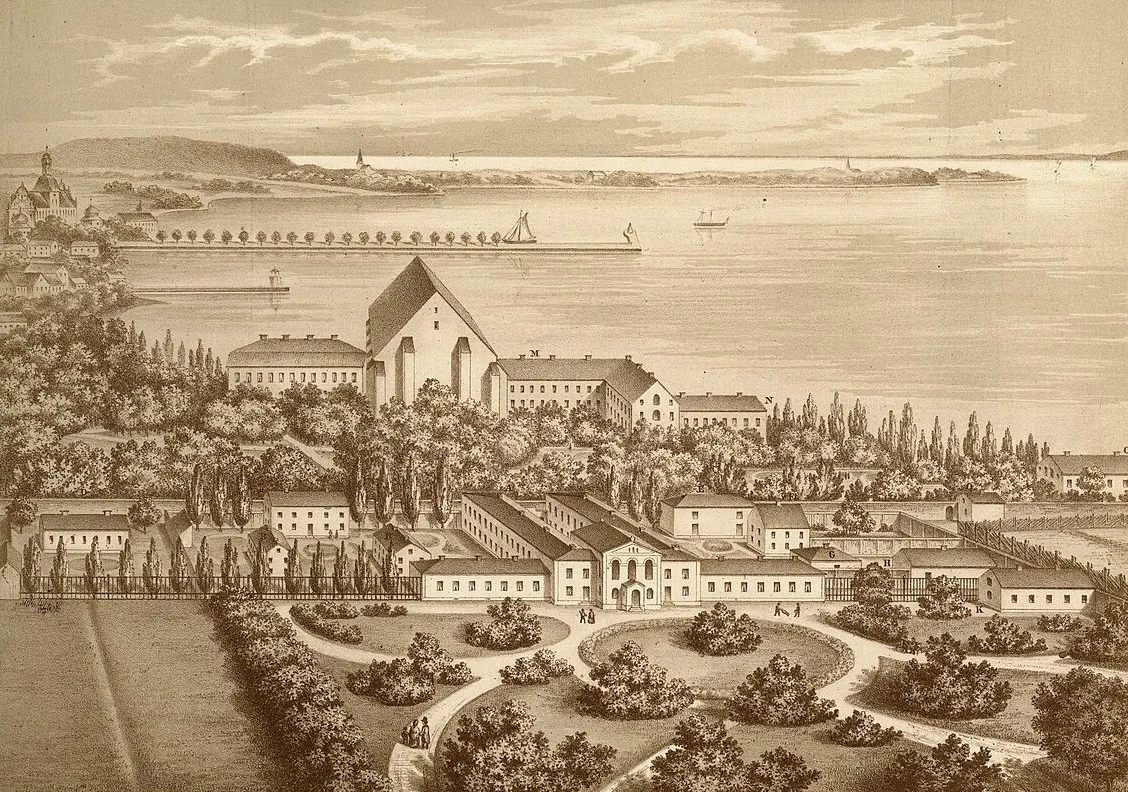

The chasuble at Högsjö Manor

In 1648, Claes Rålamb married Anna Åkesdotter Stålarm (1627–1666). As part of the marriage, she brought with her the estate of Högsjö in Västra Vingåker parish, Södermanland. It was here that the splendid textile was brought and eventually made into a chasuble.

A closer look at the chasuble reveals a cross on the back and a decorative front border, both formed with woven gold bands. These bands date from the 17th century, supporting the idea that the vestment was made soon after the textile arrived in Sweden. During services lit by candlelight, the gold and silver threads must have created a divine shimmer befitting the sacred setting.

The chasuble was used over centuries in the chapels at Högsjö Manor and remained on the estate through several changes of ownership. In 2004, the chasuble was donated to the collections of the Swedish History Museum.