Eksjö ceiling – a 17th century painting

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

Middle Ages

AD 1050 – AD 1520

Modern Age

AD 1520 – AD 2025

After the Reformation in Sweden during the 1500s, attitudes toward church decoration changed. The Lutheran doctrine emphasised preaching and the word. But unlike other Protestant movements, it did not reject images altogether, only Catholic content. As a result, 17th-century Lutheran churches often featured an abundance of paintings.

The decoration of church ceilings and gallery fronts followed well-thought-out iconographic programmes. Typically, it was the parish’s vicar who, in collaboration with the master painter, decided which motifs should be used.

The most common motifs were taken from the Bible. Recurring themes included the Creation, the Fall of Man, the Life of Jesus, the Crucifixion, and the Last Judgment. These motifs were chosen not only for their theological significance but also for their narrative clarity. They lent themselves well to visual interpretation. And, not least, there were existing sources to draw upon.

Master painter Johann Künkel

Master painter Johann Künkel and his team painted the ceiling in Eksjö’s old church in 1687. The commission was to adorn the church interior and the adjacent vestibule. This involved not only large biblical motifs but also decorative filling of all other surfaces.

The church interior

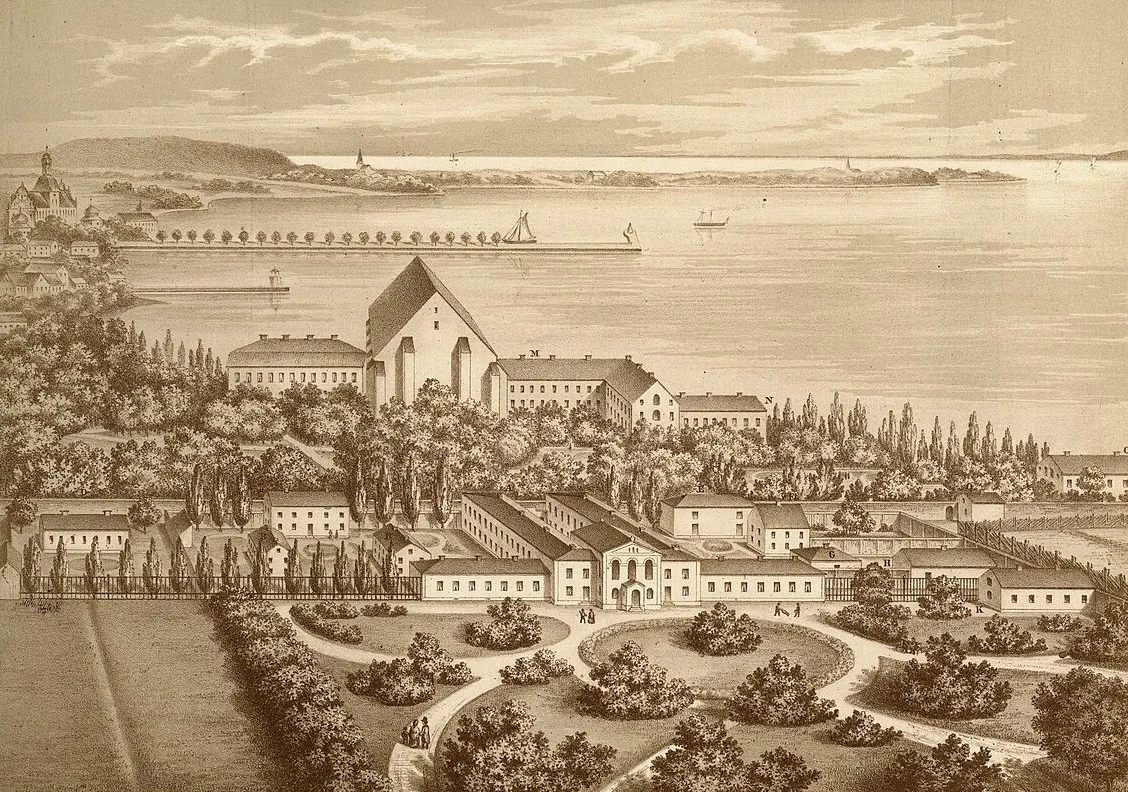

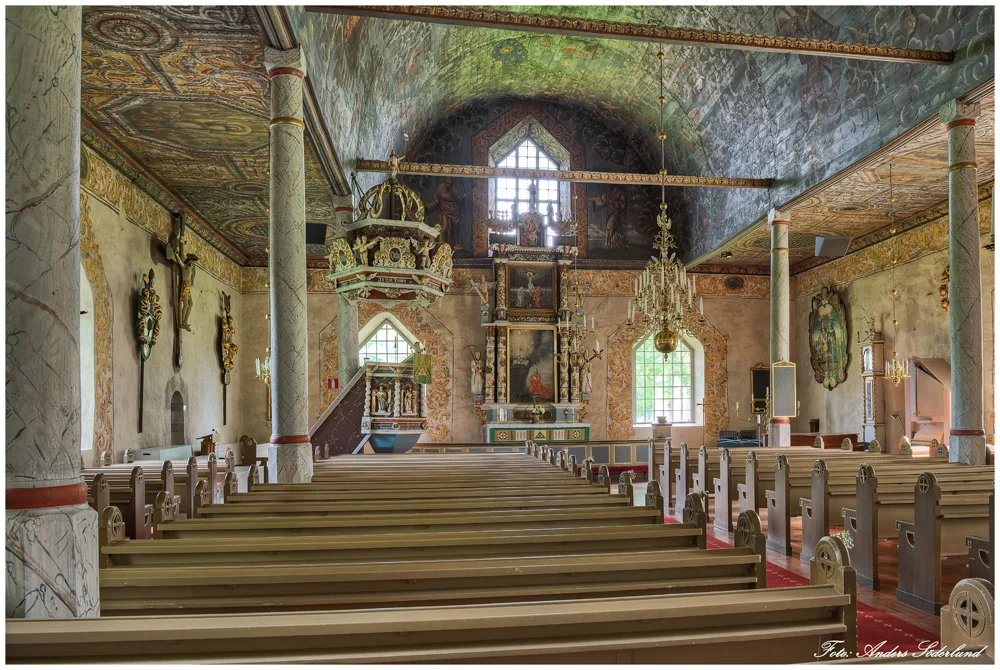

Eksjö Church had a vaulted ceiling over the nave and two flat side ceilings above the aisles. The aisles were separated from the nave by columns. The church’s interior was very similar to the nearby Norra Sandsjö Church, which still exists today. By way of comparison, master painter Johan Columbus was paid 200 riksdaler to decorate Norra Sandsjö Church in 1709. That sum would be equivalent to around 2.5 million SEK today.

Churches in the region with vaulted ceilings follow roughly the same iconographic programme. The vaulted ceiling is intended to represent an open sky, with a pair of medallions and some form of monogram or coat of arms in the centre. In Eksjö and Norra Sandsjö, the central motif is a royal coat of arms. The ceiling paintings in the aisles, arranged in boxes, were executed according to a combined typological and contrasting programme.

Different types and contrasting styles of religious or symbolic imagery

Lutheran church art aimed to envelop the viewer in the Bible. Biblical images were never solely intended as historical scenes; they were meant to feel relevant to the viewer. At the same time, the illustrations had a pedagogical function.

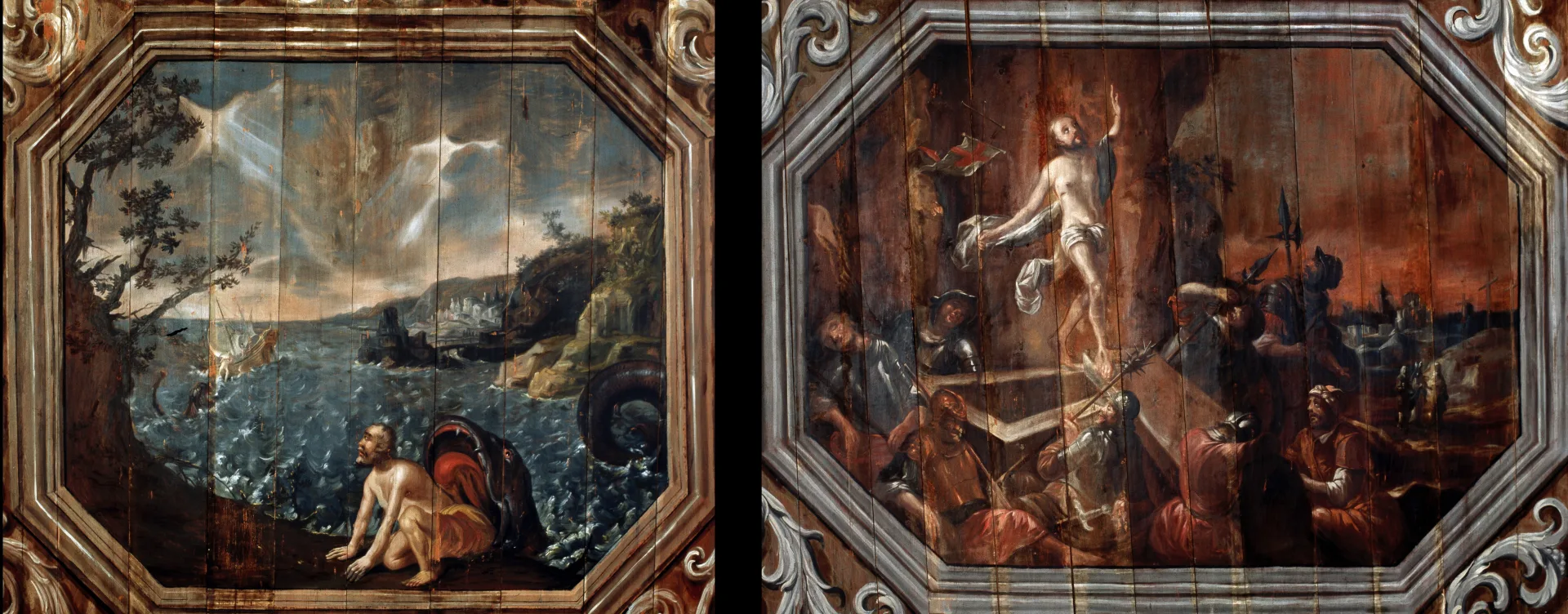

A typological way of arranging motifs involved alternating scenes from the Old and New Testaments. The idea was to show that the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus were prefigured in the Old Testament. For example:

- Jonah tried to flee God’s command to become a prophet by sailing across the sea. God then sent a storm upon the ship. The crew realised that the storm was Jonah’s fault and threw him overboard, where he was swallowed by a whale. After three days in the whale’s belly, Jonah promised to become a prophet and was spat out onto land again. (Old Testament, Jonah 1:1–13).

- Jesus lamented to God over having to sacrifice His life through crucifixion. Ultimately, He accepted His fate, was crucified, and died. Afterward, His disciples laid His body in a tomb, but three days later, the body disappeared, and Jesus rose again as Christ. (New Testament, Matthew 27:57–60 and 28:1–10).

A contrasting programme might instead show scenes from the Bible that were opposites, such as the Creation (Genesis 1–3) and the Day of Judgment (Matthew 7:7–12).

Inspiration and the final outcome

Künkel and his assistants used black-and-white templates from books, including the artist Matthäus Merian the Elder’s Icones Biblicae (Biblical Motifs), published in the 1620s. Merian’s illustrations were very popular and served as models for many Lutheran church paintings.

A church painter would always adapt the template to the existing space. Sometimes this meant omitting certain parts due to space limitations, while at other times, the motif was altered to include more stories in one image. The artist’s technical skills might also result in more complicated motifs or details being simplified or omitted.

A common method of completing painting work during the 1600s involved a single person, usually the master, sketching the design, with apprentices and journeymen carrying out the actual painting. The apprentices’ main tasks were mixing paint and cleaning. If the master had several journeymen, they would divide the work so that each person could focus on what they did best.

A comparison between the template and the final result for one of the motifs in Eksjö’s old church illustrates this clearly:

In the story of Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31), Künkel chose to condense Merian’s illustration. The background events (Lazarus in heaven and the rich man in hell) are larger and brought closer in the image. Other parts of the background have been simplified. The staircase in the main building has also been simplified, and several details, such as Lazarus’s staff and bowl, are omitted. True to Lutheran church painting style, Künkel made the clothing slightly more contemporary. The reveling company on the balcony has been entirely reimagined, and a chalice has been added.

The Eksjö ceiling becomes a museum object

During the 1800s, many rural parishes saw improvements in their finances, leading them to modernise their medieval churches. As a result, Eksjö parish decided to demolish the old church in 1887, two hundred years after the church paintings were created.

To gain permission for the demolition, the parish was required to preserve the old interior. Parts of the ceiling were therefore stored at the Nordiska Museet, while the parish kept the altar and baptismal font. The ceiling’s size meant that it remained in storage until 1946, when it was installed in the Baroque Hall at the Swedish History Museum.

However, the original arrangement of the paintings could not be maintained because the ceiling in the Baroque Hall lacks a vaulted ceiling. Therefore, some parts of the ceiling are still stored in the parish’s own storage.

Regulation of craftsmanship, in brief

The 17th-century regulation of craftsmanship meant that all craftsmen had to either belong to a guild in a town, to be employed for a year by a nobleman or a parish, or possess a royal privilege.

Only the most skilled craftsmen had royal privileges. This granted them the freedom to work wherever they chose and set their own prices. Craftsmen who belonged to a guild were tied to a specific town and had to adhere to predetermined price lists. A craftsman employed for a year had job security, but was also obligated to carry out the employer’s wishes.

The master usually had several journeymen and apprentices to assist with the work.