A Roman Empire mercenary in Sweden

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Viking Age

AD 800 – AD 1100

The Romans often wore rings to signal their social status, marital status, or family affiliation. Others wore rings set with stones for protection, each stone, according to Roman belief, offered its own form of defence or good fortune. Over time, ring-wearing became fashionable in the North as well, and from around AD 200 onwards, a wide variety of styles emerged. These ranged from simple bands, much like modern wedding rings, to highly distinctive designs featuring decorative motifs such as snakes or birds. Rings were crafted from bronze, silver, or gold. Especially among the gold rings, we see a remarkable richness of design and creativity.

Ring of gold

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

A dislike of imported jewellery

Most gold rings from the Roman Iron Age (AD 1–400) and the Migration Period (AD 400–550) were made locally. A small number of gold rings with set stones, however, were imported from the Roman world. These are exceedingly rare.

It seems that imported jewellery was generally not highly valued in Scandinavia at the time. For example, only a few Roman-style dress pins have been found, and even fewer pendants or necklaces.

One of the most striking examples of these imported Roman gold rings was found in a grave at Fullerö, north of Gamla Uppsala in Uppland. The Fullerö ring is among the heaviest gold rings known from the period, weighing an impressive 61.18 grams. Its top is set with a large, oval carnelian.

A plundered warrior’s grave

The ring was found in a richly furnished warrior grave that originally had a wooden chamber structure. Sadly, the grave had been looted before it was excavated, and some items were lost.

Gold objects from Fullerö

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Guldrummet

Still, the burial contained two additional gold rings, a gold pendant, and a Roman gold coin mounted as jewellery. There were also remains of weapons, belts with silver fittings, a gaming board with playing pieces, and more.

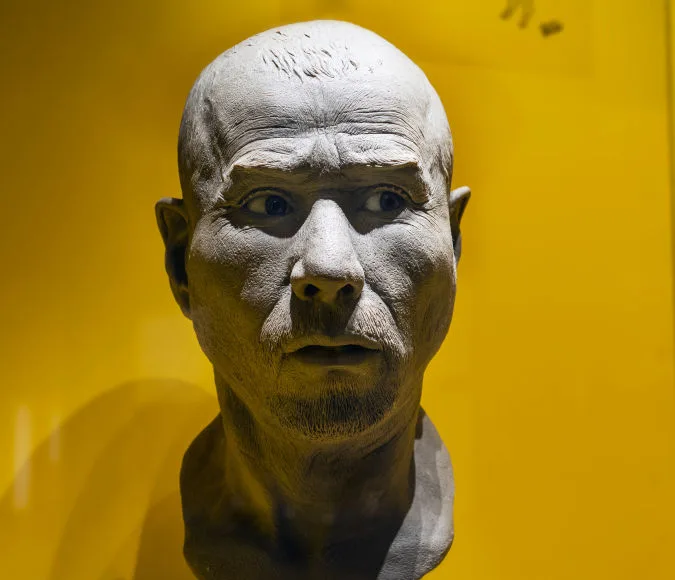

The man buried in the Fullerö grave must have been a highly influential figure in Iron Age Uppland. This is clearly shown by his grave goods, especially the magnificent ring set with carnelian.

A mercenary in Rome?

We know that the Romans rewarded allies and senior officers with gold rings as marks of valour in battle. These awards, known in Latin as dona militaria, included rings of the type found in the Fullerö grave, making it quite possible that this ring was such a military distinction.

If so, the warrior buried in Fullerö may have served as a soldier in the Roman army during the 4th century AD. This is far from unlikely. By that time, the Roman army was largely made up of troops recruited from outside the empire’s core territories.

Hard-earned knowledge in a turbulent time

Many Scandinavians likely saw military service as a way not only to earn money but also to acquire valuable skills. For instance, they would have learned how the Romans organised and commanded troops, knowledge that would have been useful in an era of instability and conflict between various groups across Scandinavia.

The man who wore the Fullerö ring may have been one of many returning mercenaries who had completed their training under Roman command. Once home, he could have used his newfound knowledge to rise to a position of power.

And the ring? He wore it as a mark of his connection with the Roman world, a visible symbol of honour, authority, and experience. Few in Iron Age Uppland could boast a ring like his.