A 9,000-year-old paddle

Stone Age

12,000 BC – 1700 BC

Bronze Age

1700 BC – 500 BC

Iron Age

500 BC – AD 1100

Humanity’s ability to travel by water has played a major role throughout history. Seafaring has existed for millennia, with people moving along coasts, rivers, and even across open seas.

One early example from Sweden is the journey to Gotland over 9,000 years ago. The people who settled on the island maintained contact with the outside world and kept pace with developments in surrounding regions. For this to have been possible, regular two-way travel must have taken place.

In prehistoric times, water connected people. Seas, lakes, and waterways were vital for travel and trade, while inland forests often posed difficult obstacles to movement.

Early seafaring and prehistoric boats

It is primarily from traces of early human activity on islands that we know seaborne travel began early. In addition, animal bones found from species that must have been hunted or fished in deep water suggest the use of boats. However, remains of boats and paddles are rare, as wood and hide only survive under exceptional preservation conditions.

The best chances of preservation are under water, in lakes, bogs, or submerged coastlines. A challenge for archaeologists is that most Stone Age coastlines in what is now Sweden lie above the present-day sea level. These ancient shores are now found in farmland and forest, where organic material has long since decayed.

As a result, the chances of finding boats once used for seagoing voyages during the Stone Age are very slim. There is somewhat greater potential to discover boats used in calmer inland waters, rivers and lakes, although water levels in these areas have also changed over time. One exception is southernmost Sweden, where parts of the Stone Age coastline, like those in Denmark, have become submerged.

One such site is Tybrind Vig in Denmark, dating to the late Mesolithic (roughly 5500–4000 BC), where three dugout-boat were found, measuring roughly 3, 5, and 9 metres long. One had been deliberately sunk, and another contained a hearth. Around 10–15 fragments of paddles were also discovered, with heart-shaped blades, four of which were decorated.

The earliest means of water travel

When people first arrived in what is now Sweden more than 14,000 years ago, the landscape was still shaped by retreating glaciers and was largely barren. They lived in open areas and hunted large land animals such as reindeer, but marine hunting and fishing were also crucial.

As trees were scarce, the earliest boats may have been made from animal hides. Eventually, forests took root and trees became available as a resource. This made it possible to construct dugout-boats from hollowed logs, as well as bark or birchbark boats. Skin boats may also have continued to be used alongside them.

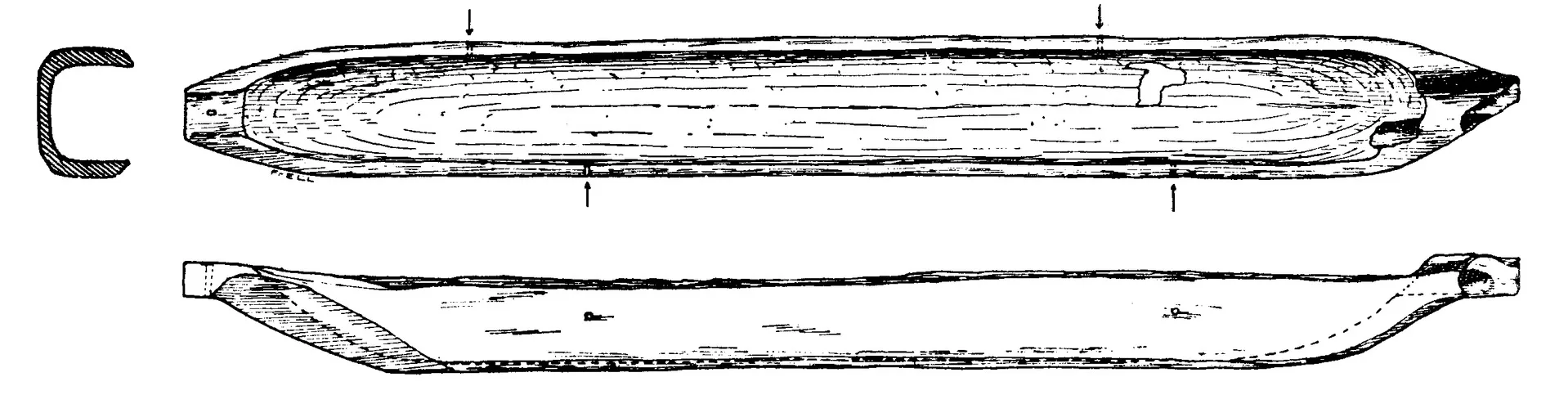

Sketch of a dugout-boat

Archeological find from Lassbyn, Norrbotten.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

There are wooden objects from later parts of the Stone Age that have been interpreted as keels from boats made of hide or bark, such as finds from Ragunda in Jämtland and Grundsunda in Ångermanland.

Dugout-boats range in size from a few metres to over ten metres. One example is a 12-metre-long Stone Age dugout-boat from Germany. Two main types of dugouts are known: a simple hollowed log, and a version with expanded sides, held in shape by ribs. These could be up to a metre wide, had thin hulls, and were often made from aspen.

This type of dugout-boat is called an äsping, and one from the Stone Age has been found in Helsinki. Dugouts may also have featured freeboards or outriggers to increase their stability at sea. A Stone Age boat discovered in Lithuania was built with outriggers along the railings.

The sensational paddle

In the collections of the Swedish History Museum, there is a paddle that has turned out to be remarkably significant. It was discovered in 1928 during peat cutting at Åkermyra in Hedemora, Dalarna. The paddle lay directly on the clay bottom, about two and a half metres down in the bog, which was fully waterlogged at the time.

Paddle from Åkermyra

The finder, Frans Perers, realised the object might be ancient. He carefully excavated it and handed it over to the local representative of the National Heritage Board for examination and age assessment. The paddle was then forwarded to the Swedish History Museum, where it became part of the permanent collection, for which Perers later received compensation.

The paddle measures just under a metre, more specifically 87 centimetres in length. The shaft is relatively round, with an average diameter of about 3 centimetres, tapering towards the end. The blade is slightly curved and rectangular in shape, with rounded corners. It measures 23 centimetres long and just over 11 centimetres wide. The paddle is made of pine wood.

Multiple dating attempts reveal its age

Frans Perers wanted to know how old the paddle was, so the Swedish History Museum sent it to the Geological Survey of Sweden for analysis of the soil clinging to the object. Based on the pollen grains identified, the paddle was estimated to date to the late Neolithic, around 2600 BC.

A second attempt to date the paddle was made in 1964. At that time, radiocarbon dating was a relatively new technique, requiring the destruction of large samples. For this reason, a sample was not taken from the paddle itself. Instead, a piece of birch wood that Perers had found alongside it was analysed. It was dated to around 5885 BC.

The story doesn’t end there. When the Swedish History Museum planned its permanent exhibition Prehistories, the paddle was once again dated. This time, improved radiocarbon methods of the early 2000s were used, which required only tiny samples. A small piece of the paddle was analysed at the Ångström Laboratory in Uppsala in 2006. The results were the dating 7040–6640 BC.

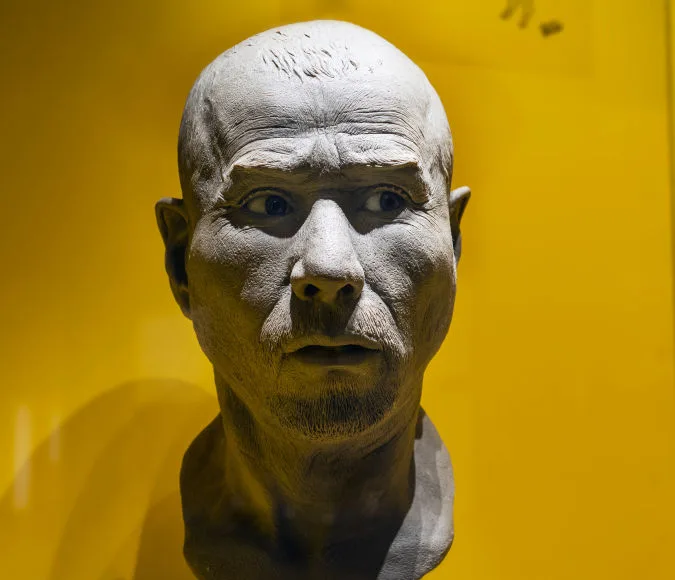

The paddle is thus an astonishing 9,000 years old, contemporaneous with the famous Barum woman, one of Sweden’s best-preserved prehistoric skeletons, also from the collections of the Swedish History Museum.