Mesolithic Period

The Mesolithic period is characterized by various types of settlements, advanced fishing installations, and early burial sites. The climate became warmer, and the landscape changed significantly.

The Mesolithic period lasted from about 9500 BC to 4000 BC and is often divided into three phases: Early, Middle, and Late Mesolithic. In southernmost Sweden, the Maglemose, Kongemose, and Ertebølle cultures succeeded one another. Along the west coast, other cultures have been identified, such as Hensbacka, Sandarna, and Lihult, while farther north distinct archaeological cultures are more difficult to distinguish.

Lifestyle during the Mesolithic

People lived as hunters, fishers, and gatherers. The only domesticated animal was the dog. Farming had not yet begun, although humans influenced both flora and fauna. They encouraged the growth of hazel trees for nuts or relocated plants and animals. For instance, hares and foxes were brought to Gotland, where no larger land animals existed when the island was first settled.

All of present-day Sweden was colonized

Life was quite mobile during this time. As the ice melted, people moved rapidly across vast areas—from the south, north, and east. Groups from the south moved northward as the ice receded. Early traces from around 9000 BC are known from Motala, and the oldest sites in the Stockholm area date to around 8000 BC. In the far north, sites such as Aareavaara in Norrbotten, dated to about 8600 BC, show that people also spread southward. Traces of northern groups have been found in Dalarna and Gävleborg from around 8000 BC. The last areas to become ice-free were the innermost parts of southern Norrland, around 7500 BC, and the earliest traces of humans on Gotland date to just before 7000 BC.

People moved frequently

During the Mesolithic period, people moved between different environments to make use of various resources, such as between inland and coastal areas. They traveled in small groups over long distances to maintain contact and trade with others. Waterways were particularly important. At times, larger gatherings took place for special occasions. How people lived depended largely on available resources and group size. In southernmost Sweden, a fermentation installation and advanced fishing structures show that some groups were already semi-sedentary 9,000 years ago.

Reconstruction of Stone Age tools. From the film shoot for Arkeologens Dotter (UR 2018). Photo: Linda Wåhlander, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC BY 4.0).

There are traces of many different types of Mesolithic sites, ranging from small temporary camps and hunting stations to large gathering places. Specialized sites have also been found, such as quartz quarries, axe-production sites, and locations where art was created. At so-called “axe sites,” traces of axe-making have been found alongside thousands of finished axes. In southern Sweden and along the west coast, heaps of mussel, snail, and oyster shells, known as shell middens, have been discovered.

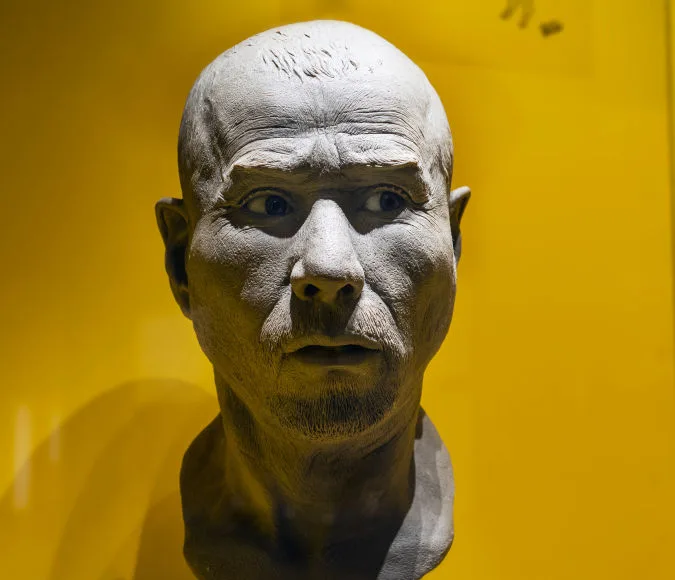

From the Mesolithic, we also have the earliest known graves in Sweden. These include individual burials such as the woman frmo Österröd, the man from Bredgård, the woman from Barum, and the man from Stora Bjärs. Later, larger cemeteries were established, such as those in Skateholm. In Norrbotten, the first burials with visible markers above ground, so-called red ochre graves, appear. Dog burials are also known. Some sites show traces of ritual activities, such as in the cave Stora Förvar on Stora Karlsö and in wetlands like Kanaljorden in Motala, where human skulls mounted on wooden stakes were found in a former lake. Both the dead and animals seem to have played important roles in the belief systems of the time.

Skull of the “Bredgård Man”

Shelters, huts, and longhouses as dwellings

Remains of houses have been found in the form of simple shelters and huts, and later also longhouses. In the far north, dwellings with sunken floors surrounded by embankments, so-called settlement mounds, have been discovered. Hearths and cooking pits show evidence of food preparation, and the earliest trapping pits also date from this period.

Climate and wildlife during the Mesolithic

The climate was warmer than before. Tundra landscapes were replaced by vast birch forests, which gradually developed into mixed deciduous forests with pine and, to a lesser extent, spruce. Large game included aurochs and wild horses for a short period, later mainly elk, reindeer, deer, and bears. Small game such as beaver, wild boar, fox, and hare were common, as were berries, fruits, nuts, and plants. The seas and lakes were rich in fish, and seals were hunted.

Animals were frequently depicted in contemporary art, as paintings on rock surfaces or carvings on tools. Both men and women participated in hunting and fishing, as suggested by grave finds, and most community members likely helped with gathering and food production.

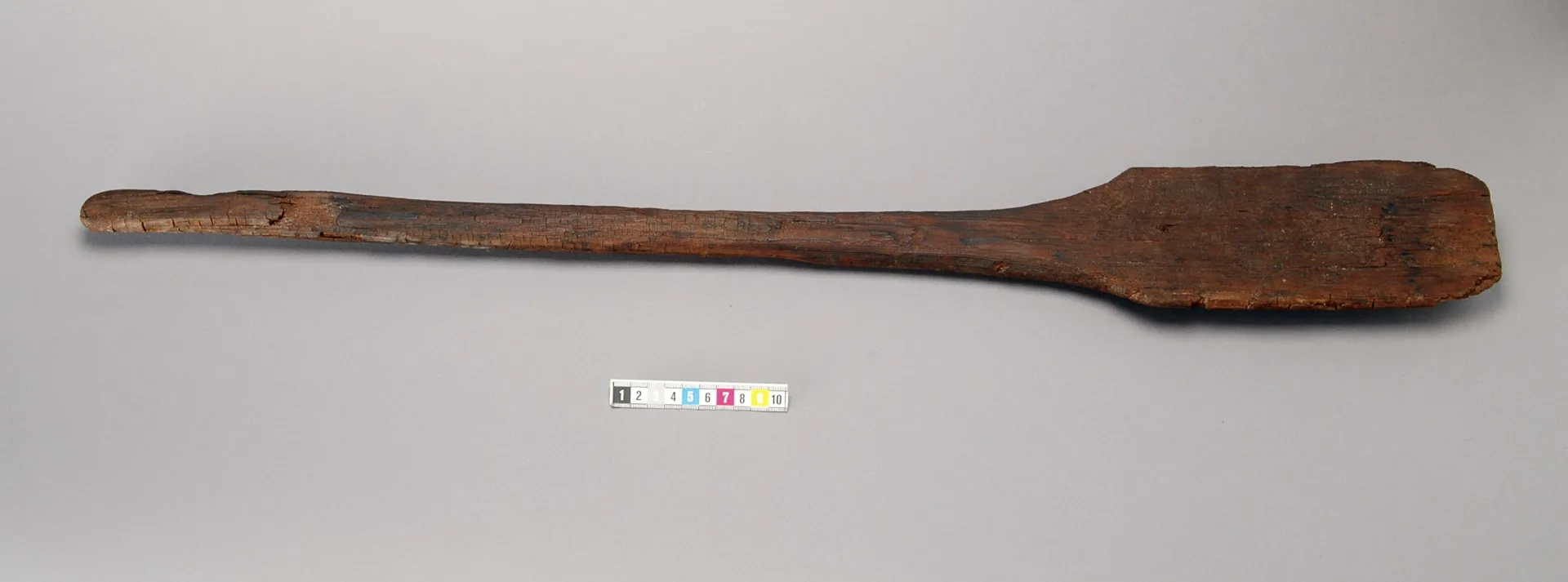

Shaft-hole antler adze

The so-called “Ystad Axe” was found in Skåne. Note the engraved depictions of deer.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Shore levels and changing landscapes

Due to melting ice and the simultaneous land uplift that occurred as the weight of the ice sheets lessened, shorelines shifted dramatically. The landscape was constantly changing. In the south, where the land uplift was smaller, coastlines were at times submerged. This also happened periodically along the southern coasts of the Baltic Sea during temporary rises in sea level, which left distinct ancient shorelines still visible in the landscape today.

Further north, the land uplift consistently outpaced the rising sea levels, causing the land to rise while former bays gradually turned into lakes and eventually dried out as the sea retreated. As a result, Stone Age coastal sites are now found deep within today’s forests at high elevations above sea level. The higher the site, the older it is gernerally. These shoreline shifts, which caused Stone Age settlements to move with the changing coasts or to be buried beneath newer layers, are therefore an important tool in dating many archaeological sites.

The Baltic Sea also changed form several times, from being a sea (the Yoldia Sea), to a freshwater lake (the Ancylus Lake), and then back to a brackish inland sea (the Littorina Sea). These changes affected the fauna, and in turn, fishing and marine hunting, particularly seal hunting. During the Yoldia Sea period, a strait opened through central Sweden, called the Närke Strait. This provided a route for seals to enter what is now the Baltic Sea, while also allowing water to drain away, exposing new land areas around the Öresund region in the south. In contrast, during the Littorina Sea period, the Baltic’s outlet was again located around the Öresund.

Microblade core

Found at Ageröds bog, Skåne.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Stone tools and techniques

The artefacts left behind by prehistoric people and preserved to this day consist mainly of stone tools such as drills, scrapers, arrowheads, and burins. We can also find traces of stone tool production, including cores, hammerstones, and whetstones. Different groups used different techniques, visible for example in the shape of the cores from which blades were struck. In the south, people continued the Paleolithic tradition of directly striking blades from platform cores.

In the north, migrating groups used a pressure technique on conical cores. These differing techniques allow archaeologists to trace where people came from, how they moved, and with whom they had contact. Over time, around 7000 BC, a new method developed: the use of elongated handle cores combined with pressure technique. This allowed the blades to remain the same size even as the core grew smaller. Handle cores are typical of the Mesolithic period.

The stone material itself also reveals patterns of movement and trade, since different rock types occur in specific regions. Flint, for example, is found only in the southernmost parts of Sweden and varies in appearance across areas. Senonian and Danian flint from southwestern Skåne can be distinguished from Kristianstad flint in the northeast, while Cambrian flint from Kinnekulle differs from Ordovician flint found on Öland and Gotland. Quartz, however, is the most common material used for toolmaking in Sweden. In northern Sweden, quartzite was also widely used, and slate appears as well among the typical materials.

High-quality quartz, quartzite, and other dense stones like flint, tuffite, and jasper could be used to produce blades. However, quartz often contains internal cracks and tends to fracture unpredictably. As a result, different techniques were developed for quartz working. These often used direct percussion from a platform, similar to the earliest flint-working methods in the south (the platform technique), sometimes supported underneath (the anvil technique).

Quartz flakes

Found in Tuna, Södermanland.

The material knapped off and used directly or reshaped into tools is called flakes, not blades. A bipolar technique was also developed, in which the quartz core was supported underneath while a strike was delivered from above on an edge (rather than from a platform). In general, stone craftsmanship during the Mesolithic was of very high quality, demonstrating remarkable skill. This period is characterized not only by the production of regular blades but also microblades, narrower than one centimeter. These very small blades were either used as they were or reshaped into tiny tools called microliths.

Not only were tools made from blades and flakes used, but larger stone tools, such as axes, were also common. These were shaped differently in various regions and evolved over time. The most common types included core-axes and flake axes in the south, Lihult axes in the west, and pecked axes in the east and north, especially in eastern central Sweden.

Core-axe

Found in Stolpe, Bohuslän.

Bone, tooth, and antler craft

Where preservation conditions have been better, we also find bones from both humans and animals. Objects such as jewelry, tools, and weapons made from animal bones, teeth, and antler also occur, along with traces of their manufacture. Tools made included axes and chisels, hammers for stoneworking, harpoons, leisters, and fishing hooks for marine hunting and fishing. Perforated animal teeth were used as beads.

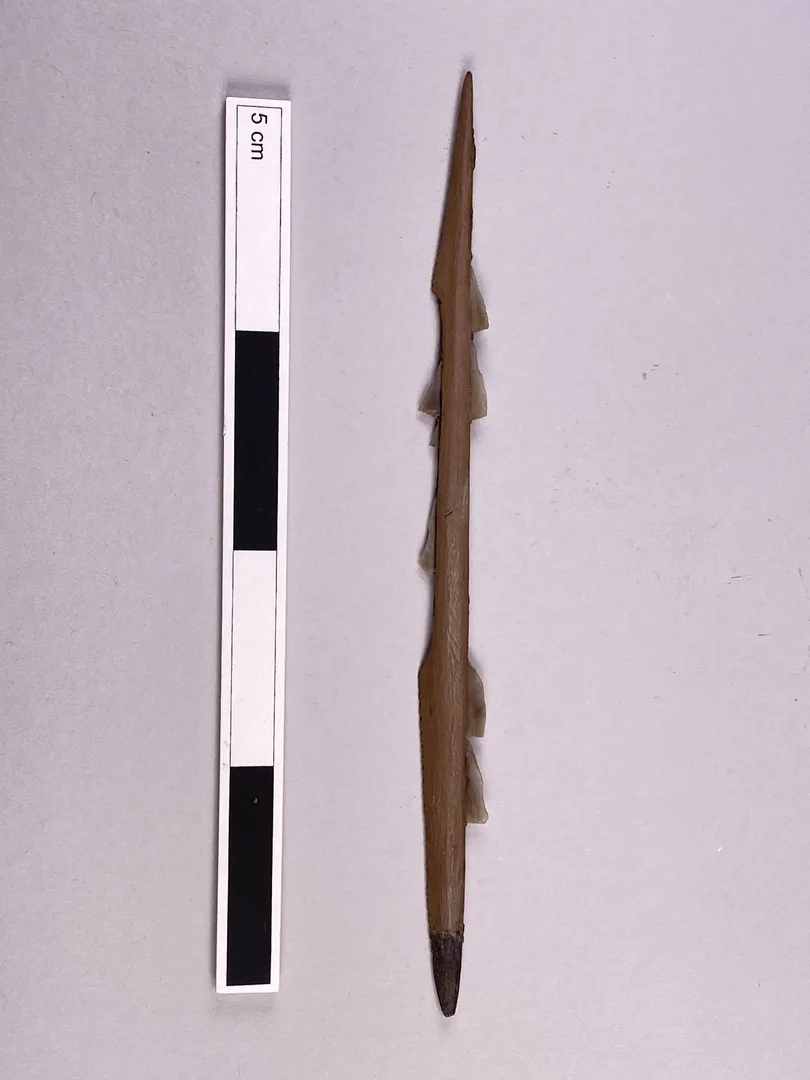

Slotted bone point

Found in Busjö, Skåne.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Composite objects in the form of bone points sharpened with microblades of flint or quartz were a relatively common hunting weapon, often shaped as arrowheads but sometimes as daggers or spear points. On the objects made of bone and antler, we sometimes find carvings, often in the form of geometric patterns but occasionally also animals and stylized humans.

Carved decorations

Found in Offerdal, Jämtland.

On view at Historiska museet in the exhibition Forntider 1

Pigments and art

Different pigments were probably used to color objects, clothing, and perhaps the human body, and traces of ochre have been found. Both yellow ochre and red ochre are known from the Stone Age. Red ochre was also used to paint on rock walls or large boulders, often depicting elk. This art, which also included carvings on rock surfaces, is difficult to date and was created over a long period, but many believe the oldest works are Mesolithic. Before the late Mesolithic, it is thought that only animals were depicted, and then in natural size. However, many of the carvings can be dated to the later Stone Age using shoreline displacement.

In rare cases, wooden objects have been preserved, such as paddles, fish traps, and other fixed fishing equipment. Textile remains from this period are extremely rare, but have been found, for example, at Tybrind Vig in Denmark. Although fur and leather were probably the most common textile materials, as indirectly indicated by tools like scrapers, the Danish finds show that ropes and textiles made from plant fibers using nalbinding were also produced. Resin is another material sometimes found. It was used to attach and seal materials, for example to fix microblades to bone spears or to seal boats, as observed at Huseby klev on Orust, and also as chewing gum. Only in the very final stage of the period did people in the far south begin using pottery, known as Ertebølle pottery, and fired clay has been found in the far north.